Just when it seemed there was no room for anything but noise in the all-consuming world of football – there was no small, quiet space for those who could contend with the sound and fury of the game – an introduction to Gate 12 in Wrexham countryside, and what lay beyond, told me otherwise, last Friday. It was a deeply moving experience.

The door and the seating area it leads to is the vision of a woman I first encountered about a year ago, whilst writing a book about the transformation of Wrexham (both the club and the town) following the arrival by Rob McElhenney and Ryan. Reynolds.

I called the book Tinseltown, although Kerry Evans’ work began long before Hollywood descended, at a time when the club could neither afford to pay him a salary as its first disability liaison officer, nor fund trips for fans who , like her, were in a wheelchair. She raised the money herself.

Attending a football match and experiencing what it is like to be a football fan is even more challenging for those on the autism spectrum who need order, routine, their own space and may find anything unexpected a frightening experience.

These are those for whom the 120-seat section, established by Evans, has become a weekly sanctuary, making Wrexham’s Racecourse Ground one of Britain’s premier environments for people with autism and physical challenges to watch football.

Wrexham fan Theo Smith, 10, poses with Kerry Evans, right, who established a 120-seat section at the Racecourse Ground so fans with autism and physical difficulties can watch football.

Local fans can visit a small sensory room inside the stand if the noise becomes too much.

Co-owner Rob McElhenney sits in the quiet, autism-friendly zone with young fans in August

Your browser does not support iframes.

The stories their parents quietly told me were a reminder of what football can bring to the lives of those with challenges, if the game lets them in.

In 15 years of reporting on sports, I can’t remember a more moving experience than listening to Helen Docking, a mother, describe the effect being able to attend a soccer game has on her 16-year-old son, Deian, who has withdrawn into himself. . , unable to form relationships, unable to communicate with others and on the fringes of an educational system from which she has been forced to remove him.

“It takes a toll on all of us,” Helen says, not far from tears. ‘We have tried everything to get him back to school, but games are the only time he leaves the house. We are not judged when we come here. We haven’t found this kind of support in the education system.’

She and other parents don’t need much to make soccer games viable for their children: just the same seat at every game in this autism-friendly zone, the familiar faces of the same hostesses (Amy and Nicky) and their deep knowledge of what makes these children different.

At half-time, the hostesses bring a snack to these young fans in their seats, because entering the concourse can be an ordeal for them. Gate 12, a designated quiet entrance, has no turnstile to deal with. That helps too.

Another mother, Sue, is always among the first here at 1pm with her own autistic son, because the experience of entering the stadium when it is empty is not traumatic. She recounts how the soccer sessions Evans organizes for some members of the group have given her son another way to access the game.

Some here will still find the match day noise too much and a small sensory room within the stand, with multi-coloured lighting which can be relaxing, often helps. An eight-year-old girl lies down on two seats and rests her head on her mother’s lap, with one of the stress-relieving “weighted blankets” the facility provides over her.

It is not only young people who find refuge. Ann Burden’s deteriorating mental health led her to leave her job as a shop assistant and enter the club to return the membership card she had had since she was a child. “It was suggested that she talk to Kerry,” she says. “The stand has given me back a part of my life.”

McElhenney and Reynolds offered to invest in an expansion of the facility and gave Evans a larger section of the stand for his area. “Thank you, but we don’t need that,” he told them. “If the section is too big, you will lose the privacy we need.”

McElhenney and Reynolds, right, offered to expand the area, but Evans refused for fear that the section would lose the privacy needed for fans.

Evans, second from left, began her job long before Hollywood stars McElhenney and Ryan Reynolds acquired Wrexham and had initially been unpaid as a disability liaison officer.

Paul Mullin took part in a community autism football session run by Wrexham last October.

She is the guardian of her small area, through whom all requests to use it and become part of it must pass. She knows every single person sitting here as Wrexham kick off against Mansfield – Theo Smith, Noah Jones, Idris Parry-Tabeart and many more – with their myriad challenges and needs.

She is in the center of the venue all afternoon, intervening only briefly at halftime, in her motorized chair, to check on those in the designated wheelchair area for visiting fans located in front of the visiting field, which McElhenney and Reynolds have . had built for her. Few clubs offer such a welcome to disabled visitors.

“She’s our social worker and the organizer of all this,” says another mother, Becky Parry-Tabeart, describing at halftime how the place has become “a magic switch” for Idris, who struggled to get by for more than five minutes in a general part of the terrain.

When Wrexham’s Paul Mullin scores in front of us, to give Wrexham the lead, our section of the stand explodes and the atmosphere allows those present to feel what football fans feel and, in some cases, express it.

After Wrexham have won the game 2-0, Gate 12 opens so those in our zone can leave. They will experience more challenges than most before their next visit to Crawley next Tuesday night, but these two or three hours have offered something indefinably special.

“Win or lose, he loves it,” Helen says, as she heads home with Deian. “I can see it in his face.”

Fans in the designated quiet zone erupted in celebration after Mullin’s goal against Mansfield.

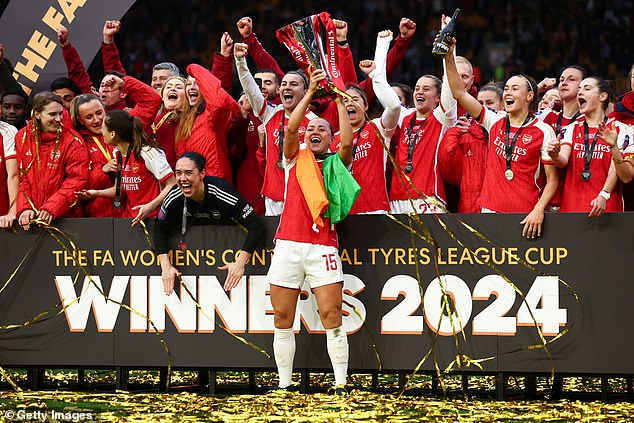

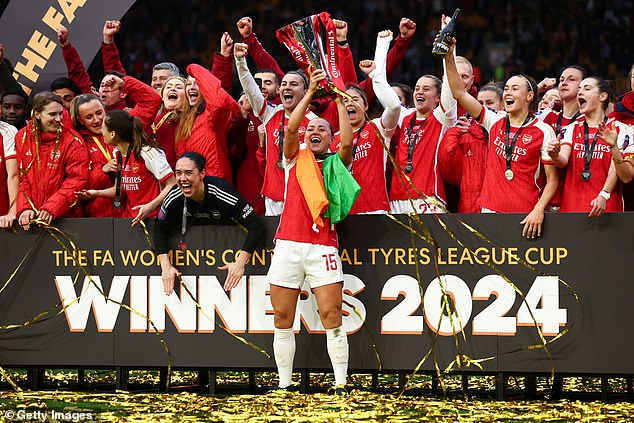

Girls show perseverance to boys.

Victory for my grandson’s team 10-0 in the last game before Easter, a Saturday morning that left a rival who arrived without substitutes worrying.

Some of their boys hung their heads when our eighth goal went in, but not Lily and Chloe, who played up front.

Ten years ago, those girls wouldn’t have had women’s football role models to draw inspiration from and they probably wouldn’t even have been on that boggy field in south Manchester, quietly showing the boys what tolerance looks like.

Girls have a wealth of role models to choose from as women’s football continues to grow.

Lyon’s limits cannot stop the start of the County Championship

Cricket Australia has restricted Nathan Lyon to seven County Championship games

Cricket Australia has restricted Nathan Lyon to seven County Championship games

I received my Lancashire CCC membership card a month ago and before a ball is even bowled, news comes that Cricket Australia will limit Nathan Lyon to seven county championship games.

It doesn’t take anything away from the feeling of anticipation about what awaits us: the freshly mowed gardens, the first ball of the new season, against Surrey, at 11am on Friday, and that beautiful feeling of the call of summer.