Amy Winehouse’s parents, Mitch and Janis, appeared on the red carpet when they attended the world premiere of Back To Black in London on Monday.

The controversial film tells the life of his talented daughter (played by actress Marissa Abela) who tragically died of alcohol poisoning at just 27 years old in 2011.

The couple, who also share son Alex and divorced in 1993 when Amy was nine, looked close and flashed smiles as they graced the red carpet.

Mitch, 73, played by Eddie Marsan in the film, cut a dapper figure in a sharp black suit which he wore with a white shirt and tie.

Meanwhile, Janis, 69, who has been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, looked gorgeous in a floral dress as she walked with the help of a frame and headed to the cinema to see herself played on the big screen by Juliet Cowan.

Amy Winehouse’s parents, Mitch and Janis, appeared on the red carpet when they attended the world premiere of Back To Black in London on Monday.

The couple, who also share son Alex and divorced in 1993 when Amy was nine, showed a united front as they graced the red carpet.

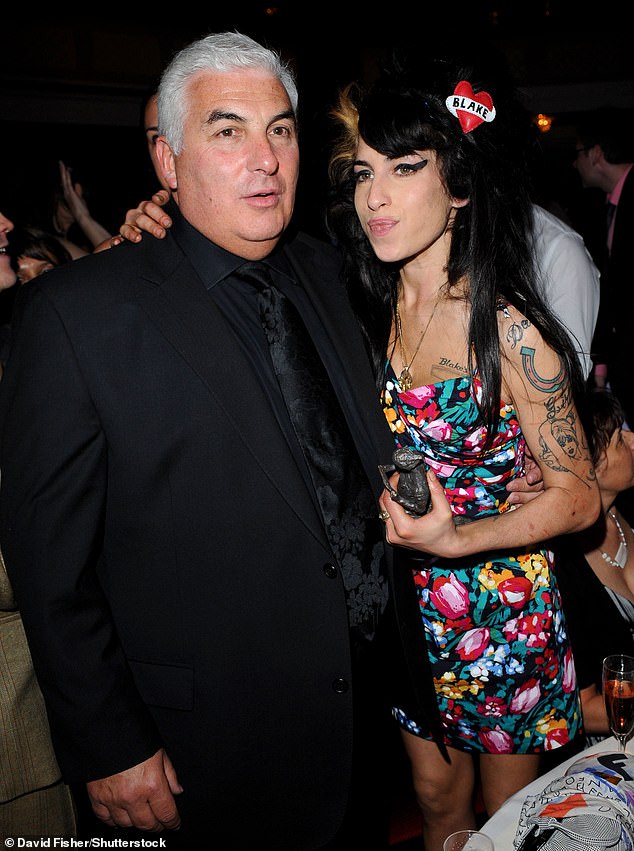

The controversial film tells the life of his talented daughter, who tragically died of alcohol poisoning at age 27 in 2011 (pictured with Amy in 2008).

Mitch and Janis split after he began an affair with his colleague Jane, a woman he would marry in 1996, before splitting last year following the strain of losing Amy.

During the flirtation, Mitch made no real effort to hide his feelings for Jane and would shamelessly bring her home on Friday nights for Jewish family dinners.

Finally, Janis had enough and bundled Amy and Alex into her car and drove to Janes’ apartment to confront the lovers.

Despite their complicated separation, Janis has forgiven Mitch and they have They remained united by their desperate quest to save their daughter from her addictions. “None of us are perfect,” Mitch said.

‘Jane was very even-keeled, as was Janis. They need to be with me: I’m a Sagittarius tiger! We actually get along better.

“We are all still friends and we are all still running the [Amy Winehouse] Foundation together.”

The biopic has sparked outrage from friends, with musician Neon Hitch calling the film “ridiculous” and “in bad taste” and saying: “I feel very strange.” Could you please let Amy rest?’

Last year, Amy’s friends expressed their fury at her father after he allowed macabre scenes of her drug overdose to be filmed in her old apartment for the film.

Mitch wore a sharp suit while Janis looked lovely in a floral dress.

Mitch and Janis (left) are played by actors Eddie Marsan and Juliet Cowan (right) in the film.

Amy is played by actress Marisa Abela

Mitch and Janis split after he began an affair with his colleague Jane (pictured with Mitach in 2013), a woman he would marry in 1996, before splitting last year following the strain of losing Amy.

Despite the breakup, Janis has forgiven Mitch and they have remained united in their desperate quest to save their daughter from her addictions. “None of us are perfect,” Mitch said (Janis and Amy pictured in 2008)

The actress, who plays the singer in the biopic Back To Black, was seen on a stretcher with an oxygen mask as she left her property in north London.

The flat is now owned by Mitch, who also appears in the scene alongside other actors playing the paramedics.

The singer’s friends were devastated that Winehouse gave her permission to use the Camden apartment to recreate one of her daughter’s darkest moments, which took place in August 2008.

This followed a marathon 36-hour drug-taking session, which ended with him being admitted to the £10,000-a-week Causeway Retreat rehab center on Osea Island, Essex.

One told The Mail on Sunday: “The fact that Amy’s father gave the go-ahead to a scene where she overdosed in the flat she lived in is disgusting.”

Last year, Amy’s friends expressed their fury at her father after he allowed macabre scenes of her drug overdose to be filmed in his old apartment for the film (Mitch and Amy pictured in 2008).

‘It was so personal and it’s so upsetting that it’s not necessary. It’s like the movie relives all the darkest moments in his life, when there were so many more incredible moments.

“All we’re seeing is depressing things, but she wasn’t like that. Mitch should be ashamed.

‘His behavior is shocking. He didn’t know what happened or how she was with all of us during those years.

“Amy would really hate for them to focus on all the dark things she went through.”

Winehouse lived at the property after the release of her album Back To Black and friends say she enjoyed happy times there.

A friend said: ‘There was always music and laughter. That was Amy. “She was very loving and very funny.”

Amy lived in the flat until 2010, when she bought a four-story house nearby, where she was found dead the following year, aged 27.

It was later confirmed that he had died from alcohol poisoning.

Amy allowed a friend to live in the apartment after she moved out, but after her death, her father took control of it.