A father has developed a new drug to treat his young son’s slowly progressing neurodegenerative disorder.

Terry Pirovolakis, 44, received regulatory approval for the clinical treatment last December, first in the hope of saving the life of six-year-old Michael, and now to help all those affected by spastic paraplegia 50 (SPG50).

This rare disease affects children’s development and causes cognitive impairment, muscle weakness and paralysis over several years. It affects fewer than 100 people worldwide and usually causes death, usually before the patient reaches the age of 30.

Such a fate awaited Michael before his father, an IT director in Toronto, stepped in. He emptied his entire savings to begin researching potential cures based on gene therapy, reading countless journals on the subject.

He also met with experts and soon signed a contract to start a gene therapy program, which involves injecting spinal fluid into the patient’s back. After years of laboratory work, the treatment began to yield results and on December 30, 2021, Health Canada launched it.

Terry Pirovolakis, 44, received regulatory approval for the clinical treatment last December, first in the hope of saving the life of six-year-old Michael, and now to help all those affected by spastic paraplegia aged 50. The couple are pictured together a few years ago, shortly after the diagnosis.

The rare disease affects children’s development, causing cognitive impairment, muscle weakness and paralysis over several years.

“On March 24, 2022, my son became the first person to receive gene therapy treatment at SickKids in Toronto,” said Pirovolakis, a father of three. Fox News On Monday, while explaining his medical odyssey.

“They said he would never walk or talk and would need support for the rest of his life,” she recalled of the 2018 diagnosis.

“They told us to just go home and love him, and they said he would be paralyzed from the waist down by age 10 and a quadriplegic by age 20,” she continued.

‘We then liquidated our life savings, refinanced our house and paid a team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center to create a proof of concept to initiate gene therapy for Michael.’

All of this happened within the span of a month, the doting father said, recalling how he flew to Washington, D.C., for a conference on gene therapy, where he met with several experts.

He then visited other places abroad, including Sheffield, England, and the National Institutes of Health at the University of Cambridge, where scientists have been studying the disease.

After months of testing, Pirovolakis and the experts he recruits saw some success: The therapy halted the progression of the debilitating disease in mice and human cells.

Pirovolakis went on to work with a small pharmaceutical company in Spain to manufacture the drug injected directly into a patient’s spine, paving the way for the procedure to one day become commonplace, despite being expensive and carrying some risks.

She realized it was slowly affecting her son a year and a half after his birth, when she noticed he was having difficulty lifting his head.

When her son was diagnosed in 2018, she was told the boy would be paralysed from the waist down by age ten and a quadriplegic by age 20. Georgia Pirovolakis is pictured here with her son.

She also detailed how the disease slowly robbed her son of movement over the first year and a half of his life, and how she only realised something was wrong when she noticed Michael was having difficulty lifting his head.

It took months of medical consultations, physical therapy and even genetic testing to discern the cause, a process he described as an “18-month diagnostic odyssey” preceding his search for a cure.

For him and Michael, however, time was of the essence, as those with SPG50 typically die before the age of 20.

“The prognosis varies from person to person, but it’s generally a progressive condition, meaning symptoms can become more severe over time,” Texas Department of State Health Services epidemiologist Eve Elizabeth Penney told Fox News.

“Over time, these symptoms can worsen, making it difficult for affected individuals to walk and perform everyday activities,” he added.

As there is currently no cure, families are forced to manage symptoms through a combination of physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy, along with medications designed to lessen side effects such as seizures.

At the time of writing, there is no FDA-approved treatment for SPG50 in the US.

The boy, now six, is showing signs of improvement, he said, although treatment remains costly for those seeing him elsewhere.

In Canada, Michael was the first to receive his father’s unique treatment, after Pirovolakis quit his job and started a nonprofit in California to dedicate himself to his worthy cause.

The company, called Elpida Therapeutics, from the Greek word meaning “hope,” now has five employees and 20 consultants, and Michael is on the mend.

Since being given the dose, the young man’s condition appears to have stabilized, his father said, and he is now able to use a device to communicate with his family and caregivers.

The same can be said for three others who were able to receive the remaining doses of the first batch of Pirovolakis, since producing the drug for each child still costs around a million dollars.

“When I found out that no one was going to do anything about it, I had to do it. I couldn’t let them die,” Pirovolakis said of the goodwill gesture. “We decided we had to help other children.”

Pirovolakis has thus opened a phase 2 study in the US, in which the three children will be treated in 2022.

Among them was 6-month-old Jack Lockard, whose mother, Rebekah Lockard, told Fox News Digital that the treatment works.

“Jack has thrived ever since,” said the mother of two, whose other daughter, Naomi, 3, also has the disease.

However, the father has opened a Phase 2 study in the US, which treated all three children in 2022. Among them was 6-month-old Jack Lockard, who is seen here being held by his mother, Rebekah Lockard. I saw her with her husband and daughter as well, and she said the treatment works.

‘He sits up alone, bangs toys together, drinks from a cup with a straw, and tries very hard to crawl.’

“Doctors and therapists share the same feeling,” he added. “The treatment works!”

But despite being approved, big pharmaceutical companies have been slow to manufacture the drug and several companies have turned it down when it has been proposed to them, Pirovolakis said.

“No investor is going to give you money to treat a disease that is not going to make a profit,” he said of the slow pace of adoption. “That’s the dilemma we’re in.”

While he looks for grants and investors, his parents are forced to pay out of pocket.

“The treatment is here, literally in the refrigerator, ready to go,” Lockard said, as Pirovolakis’ drug is now set to undergo a clinical trial at the NIH.

“The doctors are trained, but there is not enough money to make it possible.”

“Time is of the essence,” Pirovolakis added, revealing that eight doses have already been shipped to the United States. “We want to make sure that the trial goes ahead and that these children receive the treatment.”

Pirovolakis, seen here with his family, will now see his drug undergo a clinical trial at the NIH as big pharmaceutical companies have been slow to approve the drug for manufacture.

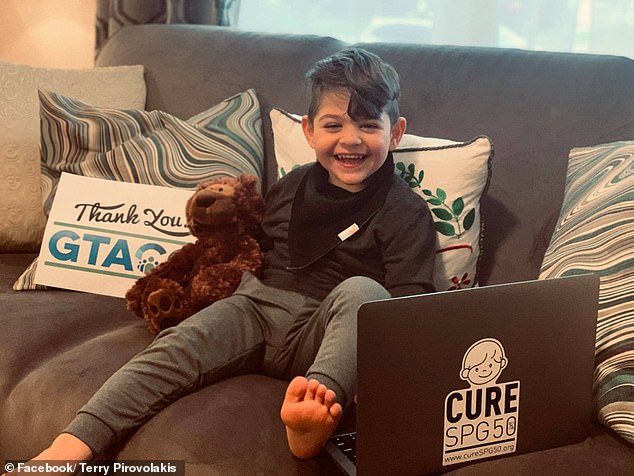

“Time is of the essence,” Pirovolakis added, revealing that eight doses have already been shipped to the United States. “We want to make sure that the trial goes ahead and that these children receive treatment.” Pictured here is his son Michael, who was slowly losing the ability to move but is now recovering.

Pirovolakis said that when his son was diagnosed, he was told the boy would be paralyzed from the waist down by age 10 and a quadriplegic by age 20.

“We were told he would never talk or walk and would have severe developmental delays. I couldn’t accept that fate for my son,” she said.

“The technology to cure our children is already here. I hope that someone with immense wealth – and, more importantly, with the vision and influence – will step in,”

The Phase 3 study for SPG50 will take place at the NIH in November.