- Trump has denied a 34-count indictment related to falsifying business records over the $130,000 payment to Daniels.

- The trial was postponed until at least April 15

- Hicks was one of Trump’s top advisers during the 2016 presidential election.

<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

Donald Trump’s former top adviser Hope Hicks is expected to testify at the former president’s trial in New York over hush money payments to porn star Stormy Daniels.

Hicks testified before the grand jury in March 2023 and will take the stand again, MSNBC reported Monday.

She was a top Trump campaign aide in the 2016 race when the alleged payment was made.

Trump, 77, has denied a 34-count indictment related to falsifying business records over a $130,000 payment to Daniels for their alleged affair.

Donald Trump with Hope Hicks as she leaves her job as White House communications director in March 2023

The trial was due to begin on March 25, but has already been delayed until at least April 15 after the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York turned over 200,000 pages of evidence.

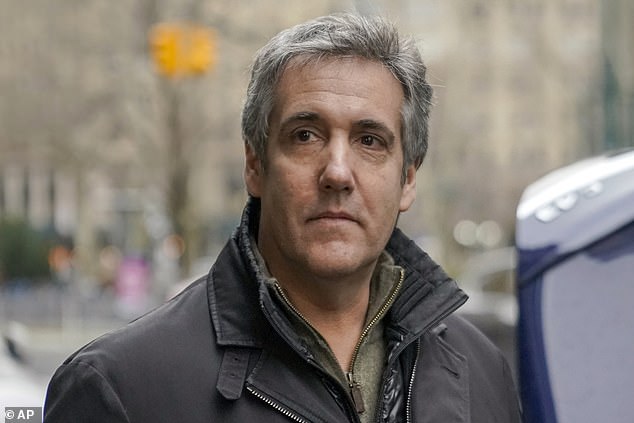

Trump’s lawyers accused the office of Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, who brought the charges, of trying to bury documents that could help them question Michael Cohen’s credibility.

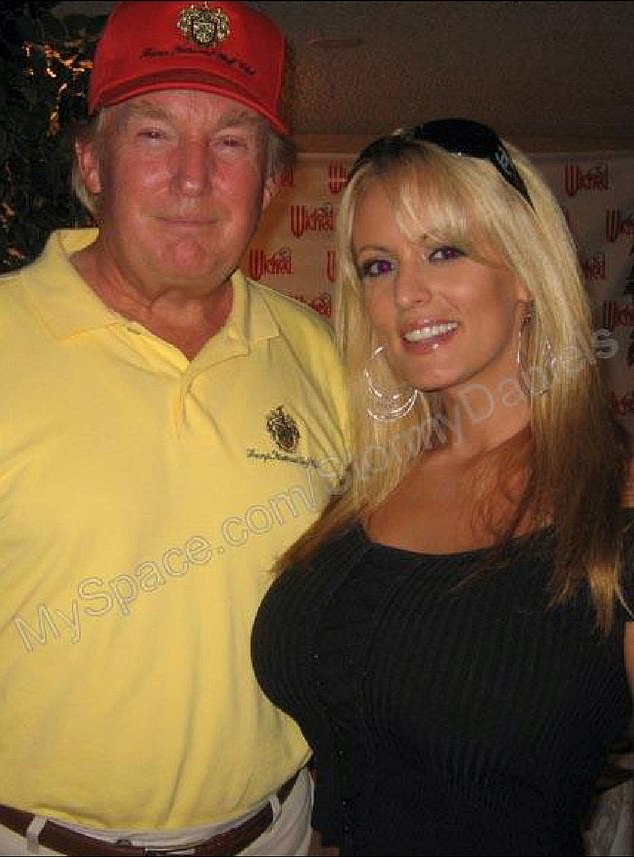

Prosecutors say Trump ordered his former lawyer and fixer, Michael Cohen, to pay porn star Stormy Daniels $130,000 to keep quiet before the 2016 election about a sexual encounter she says they had a decade earlier. , and then falsely recorded his reimbursement to Cohen as legal expenses. .

Trump denies meeting Daniels, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford.

The former president has described the trial as a “witch hunt” and a “hoax.”

Daniels is expected to be a key witness at the hearing as is Cohen. Also expected to take the stand is David Pecker, former CEO of the company that published the National Enquirer.

The date of April 15 indicates that it will be pronounced before the presidential elections in November 2024.

Trump’s lawyer, Todd Blanche, said it was unfair that Trump, who served from 2017 to 2021, was on trial while running for president.

In the hush money case, prosecutors say the payment to Daniels was part of a broader “catch and kill” scheme that Cohen and Trump devised to boost their candidacy by buying the silence of people with damaging information.

Daniels says she had a sexual encounter with Trump in 2006. Trump denies an encounter.

Trump’s lawyers say the payment was intended to spare him and his family embarrassment, not to benefit his 2016 campaign.

Cohen pleaded guilty in 2018 to federal charges of violating campaign finance laws through payment.

Trump denies having an affair with movie star Stormy Daniels

Michael Cohen, Trump’s former fixer, is also expected to testify at the trial.

The Stormy Daniels case is one of many facing Trump as he seeks a second term in the White House.

He faces three other criminal cases, focusing on his efforts to overturn his 2020 loss to Biden and his handling of sensitive government documents after leaving office in 2021. He has pleaded not guilty to all charges.