Weight-loss injections could be prescribed to children as young as six after trials showed they reduce obesity and other health problems.

Those who took liraglutide for just over a year reduced their BMI by more than seven percent and had lower blood pressure and blood sugar levels.

Experts suggest the discovery could one day help reverse the country’s childhood obesity crisis, helping them “lead healthier, more productive lives.”

More than one in five children in England are overweight when they start school, a figure that rises to one in three when they leave secondary school.

This can increase the risk of a number of chronic diseases in childhood and later in life, including heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes and some types of cancer.

Weight-loss injections have been found to reduce BMI by more than seven percent in children as young as six years old.

Vaccines such as Ozempic, Mounjaro and Wegovy have been linked to a growing list of health benefits in adults, with a study earlier this year showing they cut the chances of heart problems by a fifth.

Last year, a study of adolescents aged 12 to 18 found that giving the vaccines for 16 months halved obesity rates when given alongside lifestyle advice.

In the youngest trial conducted so far, 82 children aged between six and 12 with an average BMI of 31, putting them within the obese range, were given the drug or a placebo.

Some 56 children were given a daily injection of 3 mg or their maximum tolerated dose for 56 weeks and a dummy drug for 26 weeks, while being encouraged to eat healthily and exercise.

At the end of the trial, average body mass index was 5.8 percent lower for those taking liraglutide and increased by 1.6 percent in those receiving a placebo, a difference of 7.4 percent.

While weight gain is normal as children grow, the average weight gain was 1.6 percent with liraglutide, compared with a 10 percent gain with the dummy injection.

Nearly half of children (46 percent) who took the drug, known under the brand name Saxenda, had a BMI that was 5 percent lower.

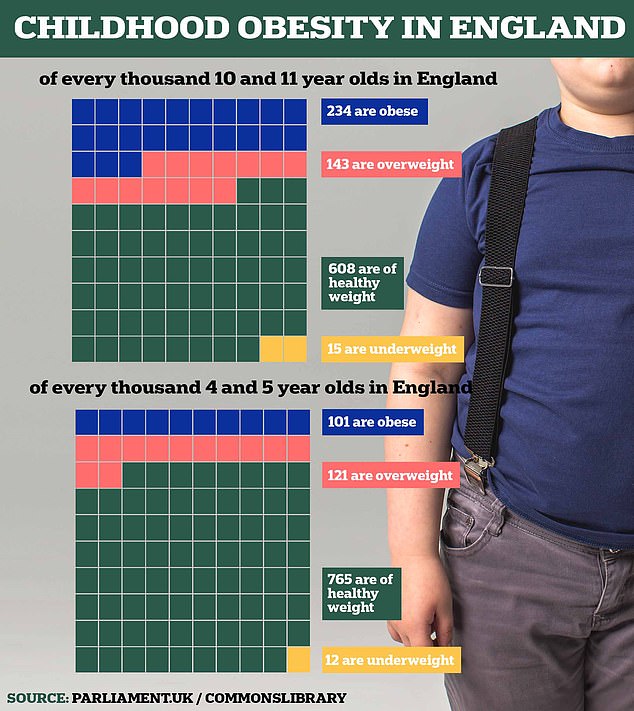

According to the latest official data, approximately one fifth of sixth-grade children are obese.

That compared with just eight percent of children taking a placebo, according to findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine and presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and Obesity in Madrid.

Professor Claudia Fox, from the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, said the drug could help when lifestyle interventions have failed.

She said: ‘The results of this study offer considerable promise for children living with obesity.

To date, children have had virtually no options for treating obesity. They have been told to “try harder” with diet and exercise.

‘Now, with the possibility of a drug that addresses the underlying physiology of obesity, there is hope that children living with obesity can live healthier, more productive lives.’

The trial’s lead researcher said a five percent reduction in children’s BMI has previously been associated with an improvement in some obesity-related health conditions.

He added: “In our study, diastolic blood pressure and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a measure of blood sugar control, improved more in children who received liraglutide than in those who received placebo.”

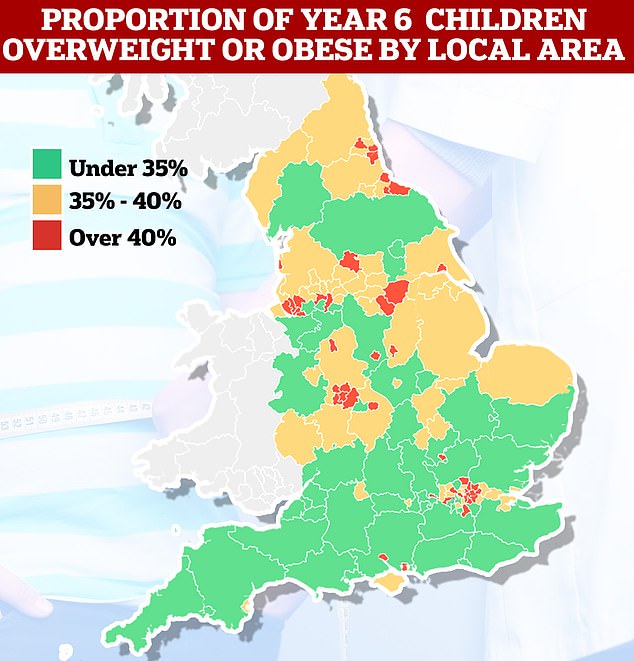

Among sixth-graders, national obesity fell from 23.4 percent in 2021/22 to 22.7 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of children considered overweight or obese also fell, from 37.8 percent to 36.6 percent. Both measures are above pre-pandemic levels.

Childhood obesity rates are skyrocketing: one in ten children in the first year of primary school is considered obese. Data from the 2021/22 academic year

The findings are likely to add to growing calls for the use of drugs such as liraglutide, which is currently prescribed to adults with a BMI above 30 on the NHS, to be expanded to include obese children.

However, side effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea were common, occurring in eight out of ten children given liraglutide, half in the placebo group.

Twelve-five percent of those taking the drug had more severe reactions, compared with 7.7 percent of the control group, leading to one in ten who received the vaccine discontinuing the shot before the trial was completed.

Commenting on the findings, Dr Nerys Astbury, associate professor of diet and obesity at the University of Oxford, said: ‘These promising findings raise the possibility that at some point in the near future safe and effective drugs may be available to treat obesity in children and adolescents.

‘Since treating children and adolescents living with obesity has the potential to have longer-lasting health benefits, although these medications are currently expensive, their value in reducing the risk of obesity-associated conditions and improving long-term health should be considered.