One of the world’s leading experts on alcohol and longevity has revealed the exact number of days, months and years that alcohol takes off your life.

And the results may surprise people.

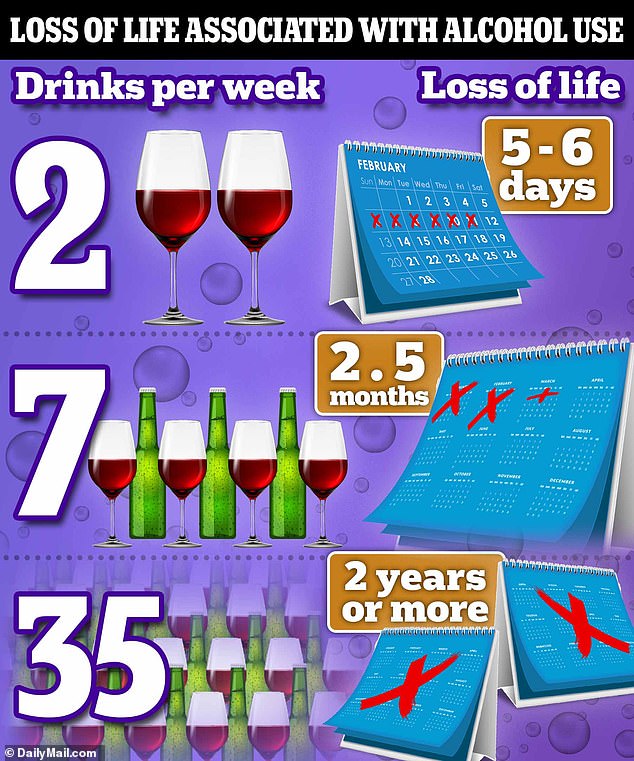

An average of just two drinks per week (bottles of beer, glasses of wine or a couple of shots of liquor) over a lifetime can shorten a person’s life by just three to six days.

Consuming one drink a day shortens a person’s life by two and a half months.

Those who drink heavily (regularly drinking 35 drinks a week, about five a day, or two bottles of whiskey in seven days) shorten their life by about two years.

That’s according to Dr. Tim Stockwell, a scientist at the Canadian Institute on Substance Use Research, who was a staunch advocate of moderate alcohol consumption until a fellow scientist alerted him to major flaws in medical research.

Citing the results of extensive research conducted over the past five years or so, including his own that served as the basis for the Canadian government’s alcohol guidelines, he said no amount is good for you.

Dr Stockwell Warnings that their predictions are averages and some people are luckier than others when it comes to their health.

But the mounting evidence raises questions about whether Americans, including those responsible for issuing health guidelines, have ignored or downplayed the risks associated with drinking alcohol because it is such an ingrained part of our culture.

Last year, Ireland became the first country in the world to pass legislation that would require all alcohol producers to include a health warning on alcoholic beverage labels.

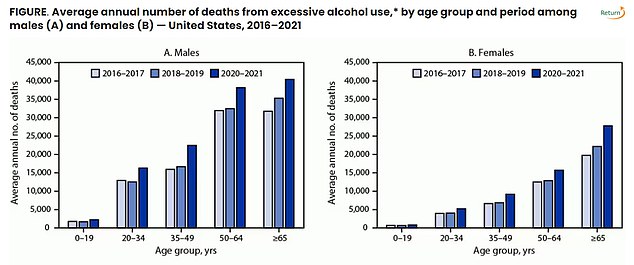

CDC charts show the average number of deaths from excessive alcohol consumption from 2016 to 2021

The labels will read: “There is a direct link between alcohol and deadly cancers.” The policy will come into effect in 2026.

Meanwhile, Canada recently proposed revised guidelines to recommend consuming no more than two alcoholic drinks per week, a drastic reduction from the previous limit of 15 drinks for men and 10 drinks for women.

And last year, President Biden’s health czar, Dr. George Koob, predicted that the USDA could revise its alcohol consumption advice to match Canada’s.

The official changes in health messaging reflect a sea change in how doctors and ordinary Americans view alcohol and how safe it is, based on major studies that debunk the myth that a little here and there is healthy.

Last year, Dr. Stockwell led a meta-analysis of More than 107 studies published over the past four decades have concluded that no amount of alcohol improves health and may actually increase the risk of dying from any cause.

And a study In 2022, a study led by scientists at Harvard University reported that “alcohol consumption at all levels was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.”

According to the CDC, the average number of annual deaths due to excessive alcohol consumption — from direct causes like car accidents and liver damage to indirect causes like mental health problems or heart disease — rose about 29 percent, from nearly 138,000 in 2016 to 2017 to more than 178,000 in 2020 to 2021.

That’s more than the number of drug overdose deaths reported in 2022, which totaled approximately 108,000.

This may seem like a higher figure than expected, given Dr Stockwell’s relatively moderate conclusions about the impact of alcohol on life expectancy.

Heavy drinkers who consume five or more drinks a day may see their life expectancy shortened by two years or more.

However, the discrepancy is probably explained by the fact that many alcohol-related deaths occur rapidly, for example a car accident and acute liver failure, which have an immediate impact on mortality rates.

Deaths from chronic diseases, such as alcohol-related heart disease, develop gradually.

Dr Stockwell said: “Alcohol is our favourite recreational drug. We consume it for pleasure and relaxation, and the last thing we want to hear is that it causes any harm… it’s comforting to think that drinking is good for our health, but sadly, it’s based on poor science.”

Alcohol has been shown to damage organs including the brain and nervous system, heart, liver, and pancreas. Alcohol itself is a toxin that causes cell damage and inflammation as it is metabolized.

It can increase blood pressure and contribute to the development of heart disease, interfere with the body’s ability to absorb nutrients, and suppress the immune system.

The belief that drinking moderate amounts of alcohol is healthy stems from a phenomenon that became known as the French paradox: the curious fact that the French, who eat high-fat foods and drink above-average amounts of red wine, have relatively low rates of heart disease, compared with other nations.

The idea that moderate drinking was healthy was appealing, and Americans quickly embraced it.

But much of the research into the supposed benefits of drinking was funded by the alcohol industry. In fact, a recent report concluded that 13,500 studies have been financed directly or indirectly by the industry.

An important trigger for the re-evaluation of this accepted logic was Dr. Stockwell’s research, which he completed with Kaye Middleton Fillmore, a sociologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

They questioned the validity of studies that point to health benefits. One reason is that people who drink red wine tend to maintain healthier diets and lifestyles, which could explain their general well-being.

This does not imply that red wine alone is responsible for the health benefits, but rather the lifestyle associated with being a red wine consumer.

Researchers have also suggested that abstainers may appear unhealthy in studies because they have stopped drinking due to a health problem.

Dr Stockwell said: ‘These abstainers are often older people who gave up alcohol because their health was poor.

‘Being able to drink is a sign that you are still healthy, not the cause of being healthy.

‘There are many ways in which these studies produce false results that are misinterpreted and believe that alcohol is good for health.’

Federal tracking of alcohol-related deaths has shown that those rates have increased over the past two decades.

Red wine, in particular, has long been considered a heart-healthy product. It contains compounds called polyphenols, which are thought to help protect the lining of the heart’s blood vessels.

One polyphenol in particular, called resveratrol, has received the most attention. However, research on its benefits has only been conducted in mice.

According to Dr. Kenneth Mukamal, an internist at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, you would have to drink 100 to 1,000 glasses of red wine a day to get the equivalent amount of wine that improved the health of the mice.

Federal guidelines recommend that men drink no more than two drinks a day and women just one. But research suggests even that is too much.

2022 Policy Statement from the World Heart Federation, WHO’s lead partner in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, sayingContrary to popular belief, alcohol is not good for the heart.

‘This directly contradicts the common and popular message that alcohol prolongs life, primarily by reducing the risk of CVD.’