Australians have been told not to panic over an outbreak of respiratory infection metapneumovirus (HMPV), which is reportedly overwhelming hospitals in China, but experts are closely monitoring the situation.

Beijing has downplayed images of crowded waiting rooms and wards posted on social media, saying respiratory infections are “less serious” and “smaller in scale” compared with last year.

This has led some to fear there are similarities with the current situation and the Covid outbreak in 2019, which was initially downplayed by China.

At the same time, UK data shows an increase in cases in recent weeks.

According to virus tracking data from the UK Health Security Agency, as of December 23, one in 10 children tested for respiratory infections in hospitals tested positive for HMPV.

However, leading epidemiologist Professor Catherine Bennett has assured the public that the HPMPV outbreak does not pose a significant threat in Australia at this time, as it is summer here, a less conducive season for respiratory infections.

“Winter is always the time when our hospitalizations for respiratory illnesses are highest, and that’s what’s happening in China now,” he explained.

HMPV usually causes common cold-like symptoms, including cough, runny or stuffy nose, sore throat, and fever, which clear up after about five days.

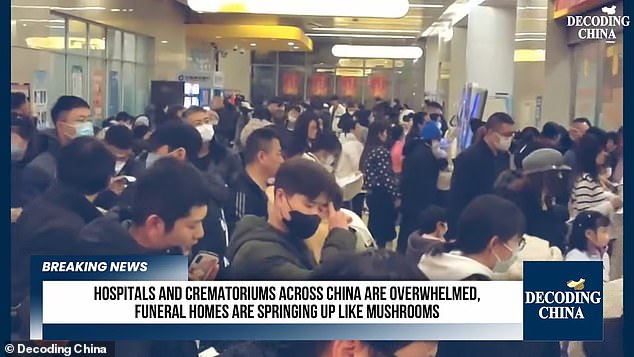

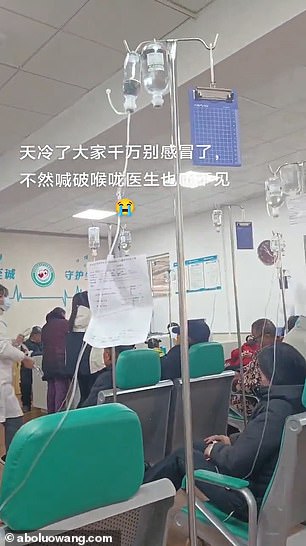

Australians have been alarmed by reports from China of outbreaks of human metapneumovirus (HMPV). The image shows the waiting room of a clinic in China.

The above are clips from videos claiming to show overwhelmed hospitals in China.

But more serious symptoms, such as bronchitis, bronchiolitis and pneumonia, can occur, and patients experience shortness of breath, severe cough or wheezing.

There is still no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for HMPV, and treatment consists mainly of controlling symptoms.

HMPV spreads through small droplets that infected people expel when they breathe, but to a much greater extent when they cough and sneeze.

Infection can occur when nearby people breathe in these droplets or touch surfaces contaminated with them, such as door handles, and then touch their face or mouth.

People with HMPV can also spread the virus without experiencing symptoms, as they are still contagious before they start to feel sick.

Unlike COVID, HMPV is not a new virus to humans; The first case of human infection was reported in 2001 in the Netherlands.

In Australia, HMPV has become the third most common virus detected in both adults and children with respiratory infections.

‘They’re comparing it to COVID, but COVID was essentially a new human virus. “No one had a strong immunity to COVID, so we were all vulnerable,” Professor Bennett explained.

«On the contrary, HMPV is a virus that has been known for this entire century. In fact, it’s reasonably common.

However, he warned that it is essential to continue actively participating in monitoring the spread of the disease, as viruses continually evolve over time.

Experts have warned that HMPV, which produces flu-like symptoms, can remain in the body for days and can therefore easily be transmitted to other people.

“The reason other countries are monitoring the situation is to check if there is any unusual increase in cases, more than what is normally seen.”

“They want to make sure that the virus hasn’t changed or that our vulnerability hasn’t increased.”

Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake, an infectious diseases specialist and associate professor of medicine and psychology at the Australian National University, said it was “vital that China shared its data on this outbreak in a timely manner,” including “data on who is getting infected.” “.

He added: “In addition, we will need genomic data to confirm that HMPV is the culprit and that there is no significant mutation of concern.”

Virus expert Dr Andrew Catchpole said it is unclear how high the number of cases is in China.

“HMPV is usually detected in the winter periods, but it appears that severe infection rates may be higher in China than we would expect in a normal year,” he explained.

“We need more information about the specific strain that is circulating to begin to understand whether these are the commonly circulating strains or whether the virus causing high infection rates in China has some differences.”

Promisingly, Dr. Catchpole noted that while hMPV “mutates and changes over time with the emergence of new strains,” “it is not a virus that is considered to have pandemic potential.”

Professor Jill Carr, a virologist at Flinders University’s School of Medicine and Public Health, also warned that the current outbreak in China was unlikely to cause a global crisis.

Leading epidemiologist Professor Catherine Bennett has reassured the public that the HPMPV outbreak does not pose a significant threat in Australia at this time as it is summer here, a less conducive season for respiratory infections.

She said: ‘This is very different to the COVID-19 pandemic, where the virus was completely new in humans and emerged from an animal contagion and spread to pandemic levels because there were no previous exposures or protective immunity in the community.’

“The scientific community also has some understanding of the genetic diversity and epidemiology of HMPV, the type of impact the virus has on the lungs, and the established laboratory testing methods – again, very different from the COVID-19 pandemic. 19, where a new lung disease was detected. As we have seen, there was little information about how the virus can vary and spread and we had no initial diagnostic tests.’

Dr Jacqueline Stephens, associate professor of public health at Flinders University, agreed.

“I think we’re more cautious about outbreaks now.”

“Everyone is very alert and you hear the term human metapneumovirus and it sounds a little scary.”