Table of Contents

- The Masters is widely regarded as one of the most unique events on the sporting calendar each year.

- This year, Augusta National Golf Club is offering a premium hospitality package of $17,000 per ticket.

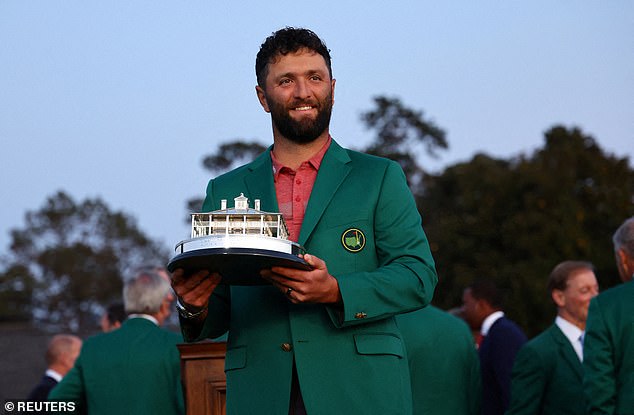

- Fans will be able to watch all the action on the 18th hole from their favorite golfers, including Jon Rahm, Rory McIlroy and Tiger Woods.

<!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

The Masters tournament at Augusta National Golf Club is considered one of the most exclusive events on the sporting calendar each year.

Trying to get tickets to the four-day event is almost impossible and those who manage to get them often have to pay a fortune for their ticket.

This year, the Masters is offering a new premium hospitality package for deep-pocketed golf fans. The new premium hospitality package has been named “Map and Flag”.

The premium experience which was announced by Augusta National chairman Fred Ridley ahead of last year’s tournament will cost a whopping $17,000 (£13,500) per ticket for the week.

Fans willing to spend money on the exclusive package that will be located across Washington Road and near Augusta National will receive a tournament badge upon arrival at the ‘Map and Flag’ venue.

The Masters is widely considered one of the most exclusive events on the sporting calendar.

This year, Augusta National Golf Club is offering a premium hospitality experience to an unspecified number of fans.

The venue titled ‘Map and Flag’ will offer spectacular views of the 18th hole

The all-inclusive club also has spectacular views, overlooking the 18th green.

Once fans are inside the venue, they will be able to take advantage of everything the package has to offer, including three dining options, a state-of-the-art entertainment system and an outdoor seating area where people can enjoy the glorious sunshine. from Georgia.

Here’s everything you need to know about the $17,000, including what the ticket offers, from unlimited food and drinks to the variety of entertainment that will be featured.

Food and drink

At the club, fans can enjoy unlimited premium food and drink during their stay at the event.

There will be three dining options available. The Grille will offer breakfast and lunch/dinner options specializing in “masterfully crafted sandwiches.”

The Carvery is the perfect choice for meat lovers as the restaurant offers a wide variety of meat-based dishes.

The last place customers can grab a bite to eat is The Marketplace, with menu options offering coffee, donuts, pastries, salads, charcuterie and cheese selections.

The venue, which will reportedly be 26,000 square feet, will also have several bars, where customers will be able to use their all-inclusive drinks account.

The prestigious package will also offer a private outdoor garden (pictured previous outdoor seating at the Masters)

Entertainment

Paying $17,000 for a ticket to any event is expensive, so when it comes to amenities and entertainment at these venues, fans expect the best.

Map and Flag will be no different, offering full coverage of every hole on 80 televisions at the club so fans don’t miss a second of the action.

There will be televisions both inside the club and also in the outside garden.

Dress code

As the Masters is one of golf’s most prestigious events, patrons are expected to dress appropriately at Augusta National.

Although no specific dress code has been stated, Augusta National Golf Club notes that since the Masters is the “world’s last non-commercialized sporting event, guests are asked to refrain from wearing corporate signage, outerwear or company-specific laces”. ‘

Instead, guests are “encouraged to use the branding provided by the Club or Masters.” laces.

Fans who purchased a Map and Flag hospitality ticket will receive a Map and Flag badge upon arrival at the club.

house rules

The Masters is well known for its strict no mobile phone policy on the course and this tradition will extend to the new ‘Map and Flag’ hospitality club.

The venue’s website clearly states that cell phones, cellular-enabled devices, pagers, electronic devices and tablets are also prohibited at the venue.

The website also asks that you refrain from taking photographs inside the venue.