Britain today imposed sanctions on the heads of the Arctic penal colony where Alexei Navalny was murdered.

Those responsible for Navalny’s detention in the brutal prison camp have been hit by an asset freeze and travel ban, the Foreign Ministry announced.

It follows the death of the vociferous Kremlin opponent in the remote IK-3 prison, known as ‘Polar Wolf’, in the Arctic Circle.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs highlighted the barbaric treatment received by Navalny, who dedicated his life to exposing the corruption of Vladimir Putin’s regime, while detained as a political prisoner.

He was kept in solitary confinement for up to two weeks at a time, denied medical treatment and forced to walk in -32°C temperatures while detained in the penal colony.

The United Kingdom is the first country to impose sanctions in response to Navalny’s death.

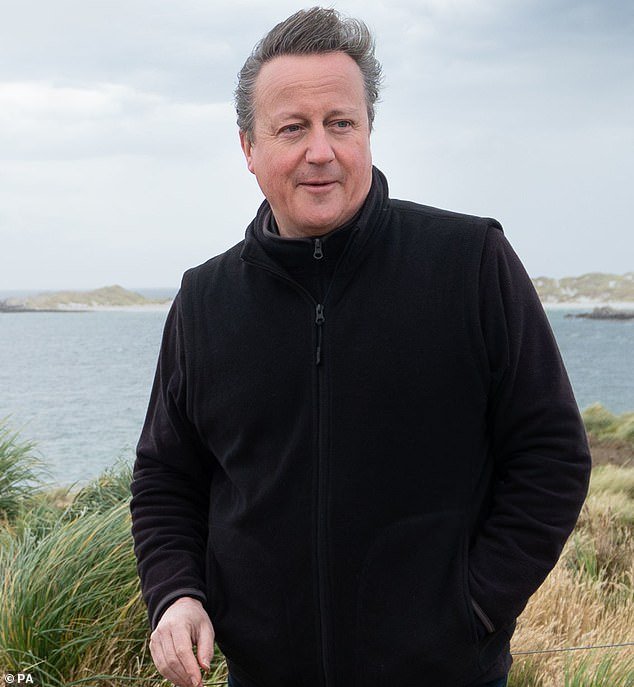

It comes ahead of a likely confrontation between Foreign Secretary David Cameron and his Russian counterpart at a G20 meeting in Rio later today.

Britain has imposed sanctions on the heads of the Arctic penal colony where Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was killed.

Navalny is said to have been knocked unconscious and died suddenly on Friday after a walk through the penal colony where he was serving a three-decade sentence.

The sanctions were announced ahead of a likely confrontation between Foreign Secretary David Cameron and his Russian counterpart at a G20 meeting.

Lord Cameron to attend Brazil summit where he will face Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov

Lord Cameron said: “It is clear that the Russian authorities saw Navalny as a threat and repeatedly tried to silence him.”

‘FSB agents poisoned him with Novichok in 2020, imprisoned him for peaceful political activities, and sent him to a penal colony in the Arctic.

‘No one should doubt the oppressive nature of the Russian system.

“That is why today we sanctioned the highest prison officials responsible for his custody in the prison colony where he spent his last months.

“Those responsible for the brutal treatment of Navalny should have no illusions: we will hold them accountable.”

Navalny, 47, is said to have been knocked unconscious and died suddenly on Friday after a walk through the penal colony where he was serving a three-decade sentence.

Western nations and Navalny supporters have said Putin is responsible for Navalny’s death.

But the Kremlin has denied involvement and said accusations that the Russian president was responsible are unacceptable.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs named six sanctioned people: Colonel Vadim Konstantinovich Kalinin, head of the ‘Polar Wolf’ penal colony, as well as five deputy directors Sergey Korzhov, Vasily Vydrin, Vladimir Pilipchik, Aleksandr Golyakov and Aleksandr Obraztsov.

The six men are now banned from entering Britain and are subject to an asset freeze which prevents UK companies and individuals from dealing with them.

Lord Cameron will attend the G20 foreign ministers’ meeting in Brazil today, where he will face Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov.

He will condemn Putin’s continuing war in Ukraine and emphasize the need for nations to adhere to the rules-based international order when he speaks at the Rio summit.

The Foreign Secretary said: ‘We need to adapt international rules and institutions to the challenges we face today. This means reforming the rules-based international order, not breaking it.

‘The Kremlin pays lip service to concepts like sovereignty, while openly undermining them. “Unlike Russia, we combine our words with actions.”

Britain had already sanctioned 13 people in response to Navalny’s Novichok poisoning in 2020.