Lauren Sisler still plays the VHS tapes. She is transported back to old gymnastics competitions after long trips with her parents and brother Allen.

“We would get in the car and drive for hours,” Sisler explains. Even now, he can still make out their voices in the crowd. “I can hear my parents screaming,” recalls Sisler, now an award-winning reporter for ESPN. You can make out his nickname – Ouch! – and his father’s piercing whistle.

What she never heard? A cry for help. Not in those videos. Not at home. Not even in the darkest hours, when opioid addiction took hold of his parents and “devastated their lives.” Not until it was too late.

“They felt so ashamed and wanted to keep pretending that everything was fine,” Sisler says. “But not everything was fine.”

In March 2003, when Lauren was just 18 years old, her father called her. Mum Lesley had died aged just 45. When he flew home to rural Virginia, his father was gone too. George, known as Butch, was only 52 years old.

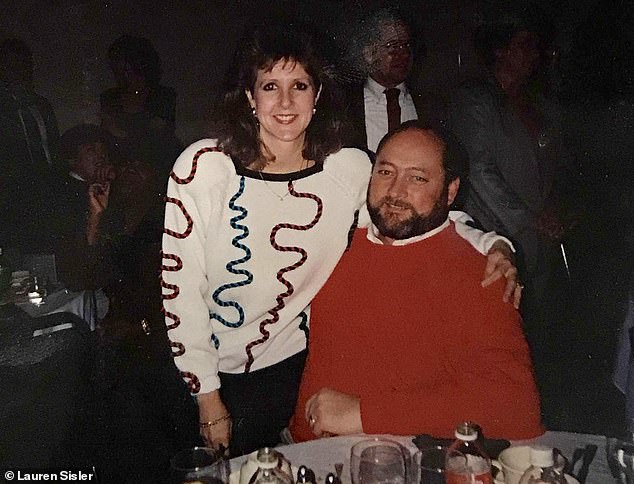

ESPN reporter Lauren Sisler opened up about losing her parents just hours apart.

Lesley and George ‘Butch’ Sisler died back in March 2003. They were 45 and 52 years old, respectively.

“It’s like someone took your life with a baseball bat and shattered it into a million pieces,” he says.

He had taken a fentanyl patch out of the freezer, sucked on it and overdosed, hours after his wife did the same. George was found on the kitchen floor and Lesley on the porch.

It was a devastating end to a downward spiral that began – many years earlier – with routine surgeries and regular medication. A tragedy that unfolded without anyone realizing it. One that left Lauren, who had $50 in her bank account, and Allen with a funeral bill, but very little else. The family home was seized and its contents auctioned. Sisler barely recognized his parents in their coffins.

“It’s like someone took your life with a baseball bat and shattered it into a million pieces,” he says. Two decades later, Sisler is 39 years old and lives in Birmingham, Alabama. The scars of that day still linger, in his response to the smell of cut grass and his reaction when college football stars took pills. The questions she asks coaches, the way she gives birth and the conversations she wants with her 15-month-old son Mason.

For a time, the ESPN reporter fled reality. She chose to make up her own story, leaving aside both the addiction and the overdose. However, he has spent the last few years filling in the gaps and answering lingering questions.

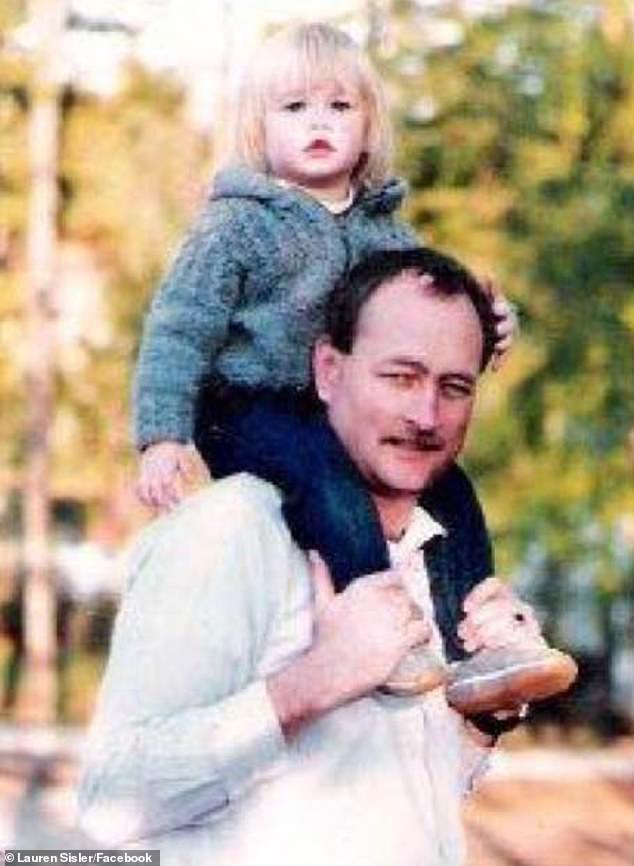

Sisler enjoyed a happy childhood even as his parents waged a secret battle with addiction.

The ESPN reporter has her own family with her husband John Willard and son Mason.

Earlier this month, Sisler released Shatterproofa book detailing his journey from shame to the ‘Sideline Shimmy’ he hosts on ESPN every Saturday.

“It forced me to delve into things and areas that I had never wanted to open the door to,” Sisler explains. “Sometimes when you put things on the shelf, it’s easier to just walk away from them.” But? “Opening those boxes, looking at them and finding out what was behind all of this has been really healing for me.”

What has become clear: the signs were always there. “My parents would walk around the house, or we would go to gymnastics meets, and they would have fentanyl suckers in their mouths,” he recalls. ‘I’m sitting here thinking, “Oh, this is normal.”‘

His mother was also writing $10 checks to the electric company, just to keep the lights on. Lauren never knew how to connect the dots and discovered that the family finances were in shambles.

He also didn’t care when his father watched ‘A Knight’s Tale’ over and over again. “I remember those end credits playing over and over again for like a month.” I was a little confused (“It’s a good movie, but not that good.”). Only later did reality arrive. “He would fall asleep every ten minutes, far away in the air, just pointing at the TV,” Sisler explains.

As a teenager, alarm bells started ringing when arguments between her parents escalated. “I later found out that my father was taking my mother’s medication,” she says.

Sisler watches old VHS tapes, where she can hear her parents supporting her in the crowd.

She then earned a gymnastics scholarship to Rutgers before family tragedy struck.

But the ESPN reporter still believed in the cover stories. On the eve of Thanksgiving 2002, Sisler was returning from Rutgers (he was on a gymnastics scholarship) when they found his father on the couch. He was blue, he wasn’t breathing. He had sucked on a fentanyl patch knowing it could kill him. Sisler was told he had simply had a bad reaction to blood pressure and cholesterol medications.

That was one of the last warning signs before tragedy struck. But he had good reason to assume that everything was fine. Sisler was born in Guantanamo Bay; his father battled alcoholism and post-traumatic stress disorder after serving in the military. You could be “lazy” and spend money they didn’t really have. But his mother? —So according to the rules. Hence, Sisler never worried when he underwent neck surgery and was prescribed medication to treat the pain.

He also felt no danger when his father underwent back surgery and began taking opioids after visiting a pain doctor. After all, they had built a very happy home.

“When I smell fresh grass,” Sisler explains, “I think of jumping on the trampoline (or) being on the balance beam…my brother and I were always loved.” “Sometimes I think maybe it’s a mistake,” he says.

“I just wish my parents had been more open.” That could have stopped the spiral. All Sisler’s wishes said? “We need help.” That’s why she is determined to have a more open and honest relationship with her own family. He has already paid too high a price.

After her parents’ struggles, she wants to have a more open and honest relationship with her son.

“I wasn’t home when my parents died,” the ESPN reporter says. They had spoken on the phone a few hours before. When her father called again in the early hours: ‘Lauren, your mom died,’ she collapsed to the floor. Sisler’s roommate started shaking her, thinking it was a nightmare. Soon the pain had doubled.

When Sisler was in high school, regular shipments containing a 90-day supply of pills, opioid lollipops and fentanyl patches arrived home. When they died, their parents were outgrowing them. Police reportedly found empty bottles containing 348 OxyContin pills, 60 oxycodone pills and 82 other painkiller pills.

Part of the writing and healing process involved reconstructing that tragic day. “All we had to read was three paragraphs from when my father called 911… and then what was shared at the hospital,” Sisler explains.

For a time, he faked phone calls, “just to escape the reality that they weren’t here.” He eventually told people that his mother died of respiratory failure and that his father suffered a heart attack. Rumors circulated throughout Giles County that it was a murder-suicide.

A fact that no one could hide? His parents did not have a will. “So their cars were repossessed, the house was repossessed, and literally everything we owned was packed up… and sent to auction.”

Sisler, now an ESPN sideline reporter, talks with legendary Alabama coach Nick Saban

The award-winning journalist visits her parents’ grave with her young son, Mason

His brother, then in the navy, managed to recover some family heirlooms. Thanks to the local community – who raised a few thousand dollars – and a message that circulated around the auction house: don’t bid against the family.

Allen got some jewelry, his father’s dog tags and his coin collection. And their weapons too.

Sisler also learned some important lessons from the tragedy. Now, at work, the focus has shifted from games to stories. “It’s really helped me dig beneath the surface,” he says. Meanwhile, his own relationship with medicine has never recovered.

“I do everything I can to stay away from painkillers,” Sisler explains. When she gave birth, the journalist insisted that she wanted to avoid opioids. On the bench, the 39-year-old gets “excited” every time she sees a player taking medication immediately after an injury.

“Everyone is chasing that dream,” he says. And that could mean “taking something that can ultimately alter your life.” The problem? “You can’t see that far in front of you.” Not everyone can see that a quick fix can lead “down a dark path that could ultimately end in a tragic situation like my parents.”