He was an explosive addition to the Love Island villa in 2019.

And while it became a matter of show legend due to his fight with his then partner Anna VakiliIt is now unrecognizable due to an image review.

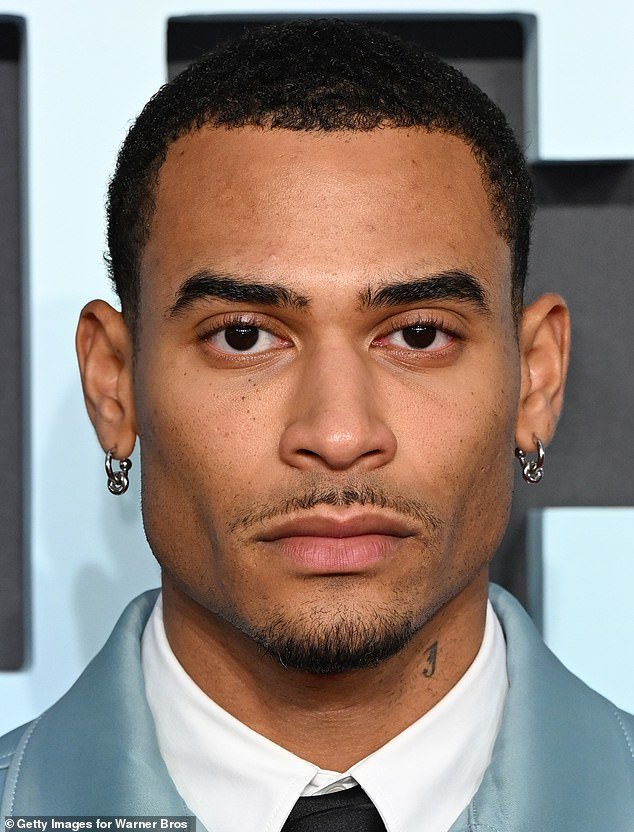

While gracing the red carpet at the Challengers UK premiere at Odeon Luxe Leicester Square on Wednesday, the star flaunted a completely different look.

After shaving off her signature locks, the style chameleon ditched the risqué ensembles she’s favored lately in lieu of a sleek new look.

Showing off his shaved head paired with a perfectly tailored cornflower blue jacket, crisp shirt and black tie, the reality hunk was truly unrecognizable – but can you guess who he is?

This Love Island star looked UNRECOGNIZABLE as she ditched her trademark curls for a close shave and showed off a stylish custom-made red carpet at Wednesday night’s Challengers premiere.

While gracing the red carpet at the Challengers UK premiere at Odeon Luxe Leicester Square on Wednesday, the star flaunted a completely different look.

It’s Jordan Hames!

The model has surprised with his chameleonic appearance since his time on the program, his latest image version being the cleanest to date.

In June last year, Jordan surprised fans again as he now moved away from the Love Island look in favor of a new, much more extravagant look.

In an advert for Love Island sponsor eBay, which aired during last year’s summer season, Jordan was seen going through her wardrobe and trying on various outfits in a nod to the circular fashion trend permeated by the auction site.

Fans were impressed by his transformed look in the sneak peek before the show, with social media users writing: “Jordan Hames in the ad, he’s had a crazy glow since LI… Also, Jordan Hames’ glow It’s been astronomical.”

Now he has changed again, with his new dark, clean-shaven hairstyle and designer facial hair, which comprises a thin mustache and a beard only on his chin.

The model appeared on the fifth series of Love Island and is best known for his tumultuous relationship with Anna.

It’s Jordan Hames! The model has surprised with its chameleonic appearance since its time on the program, its latest version being the cleanest to date.

In June last year, Jordan surprised fans again, as he now moved away from the Love Island look in favor of a completely new, and much more extravagant, look.

Now he has changed again, with his new dark, clean-shaven hairstyle and designer facial hair, which comprises a thin mustache and a beard only on his chin.

During the iconic fight, Jordan received his partner’s wrath when he tried to “move on” with India Reynolds just days after asking Anna to be his girlfriend.

His fellow islanders were seen trying to calm the situation, but it all became too much and an explosive fight ensued.

Anna, enraged, approached Jordan and shouted: ‘You just asked me out and you like it, that’s what an idiot you are. What the hell!…

‘Are you really that idiot? You ask a girl out. What are you talking about? Then I have the right to know that you are my ‘boyfriend’. Damn fake idiot.

The scenes shocked viewers and Anna later revealed that the full extent of the dispute was not shown on camera, admitting that producers had to intervene and take her away to calm her down because she “went a little crazy”.

Shortly after the fight, the couple was kicked off the island after receiving the fewest votes from the public. The couple claimed they would be “civil” towards each other upon leaving the villa, but it appears there was no love lost between the pair.

The model appeared on the fifth series of Love Island and is best known for his tumultuous relationship with Anna (pictured in 2019).

he has npw

Jordan was later linked to Ferne McCann after the pair were seen kissing.

He is now said to be dating model Millie Hannah, and the pair are said to have bonded over their shared love of fashion.

Before entering the villa, Jordan almost went bankrupt after flying to America to try and advance her modeling career. He now works with many renowned brands including Sky, Tom Ford and Jean Paul Gaultier.

She mixed up her look after the pandemic, swapping her typical sporty style for daring, high-fashion pieces.

The model has delighted her 746,000 Instagram followers with her eccentric outfits, sports skirts, crop tops and even a gas mask (pictured in December 2022).

The model has delighted her 746,000 Instagram followers with her eccentric outfits, wearing skirts, crop tops and even a gas mask.

On social media, shocked fans wrote: ‘Jordan Hames’ brilliance needs to be studied #LoveIsland’; ‘Jordan Hames has this Lil Lenny Kravitz thing on today and it looks great. he’s a different kind of alt to dami but also…yum x’;

‘I love Jordan Hames’ little rebrand since he left Love Island, he just looks great’; ‘the lennykravitzfication of jordan hames was so sexy’; ‘Hear! Love Island Jordan’s fashion transformation made me forget all his crimes against humanity. I’ll never be able to say “Who is Jordan” again?

She mixed up her look after the pandemic, changing her typical sports style for daring and haute couture garments.