Dr. Wu’s obsession with the immune system began after observing bone marrow transplants when she was an internal medicine physician.

When his second grade teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, Catherine Wu drew a drawing of herself “making a cure for cancer.”

While that is the dream of many doctors dedicated to oncology, for her it is becoming a reality.

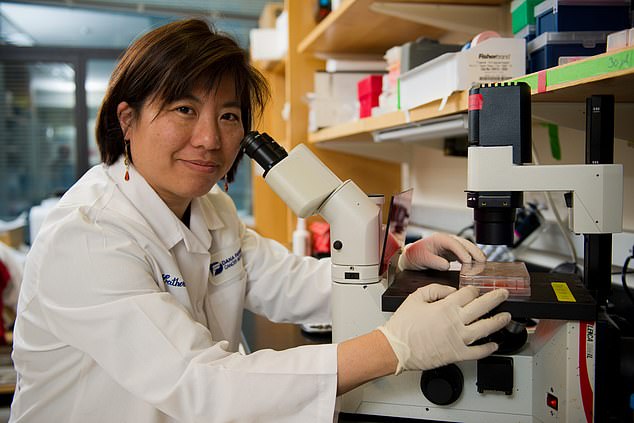

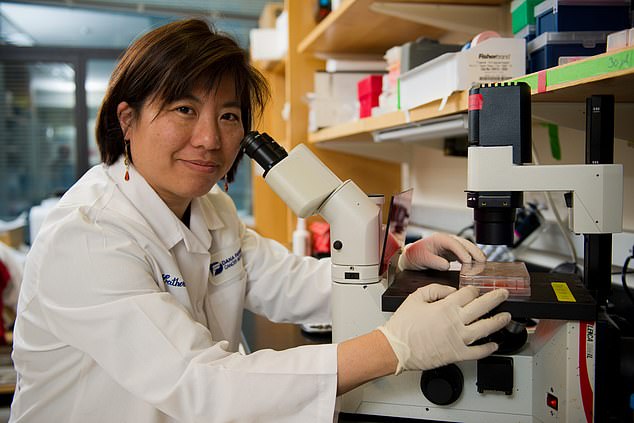

Dr. Wu, now an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, has pioneered research driving a new frontier of “personalized cancer vaccines” that are producing unprecedented levels of protection in clinical trials.

Each person’s cancer is genetically unique, and Dr. Wu and her team discovered how to identify these mutations and harness the body to fight them.

By taking this genetic data and programming it into vaccines, the body can become a powerful cancer-killing machine.

Results from early-stage trials show that the vaccines are increasingly promising for hard-to-treat cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, and could be used for many of the 200 forms of cancer.

His work has already won a Nobel Prize for his “decisive contributions” to cancer.

Dr. Catherine Wu, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, has paved the way for the development of cancer vaccines specific to individual tumors.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which selects Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, last week awarded Dr. Wu the Sjöberg Prize for her work.

Born in New York, Dr. Wu’s obsession with the immune system began after observing bone marrow transplants when she was an internal medicine physician and saw firsthand how they regenerated blood and the immune system to fight cancer.

“I had really formative academic experiences that made me really interested in the power of immunology,” he told CNN.

“Before my eyes there were people who were being cured of their leukemia thanks to the mobilization of the immune response.”

The idea of a cancer vaccine has been around for dozens of years, but many have failed in the past because the right target has not been found.

Dr. Wu was able to discover the key to making cancer vaccines work. Together with his team, he discovered how to identify the tumor’s unique neoantigens.

These are proteins that form in cancer cells when mutations occur.

These tumor neoantigens can be identified as foreign by the T cells of the immune system and then attacked.

Dr. Wu identified the patients’ neoantigens by sequencing the DNA of healthy and cancerous cells.

Copies of the neoantigens were then inserted into a personalized vaccine to activate the immune system to attack cancer cells.

Dr. Wu was determined to test the technology in patients with advanced melanoma in a trial.

But the suggestion that each patient in the trial would receive a personalized vaccine was difficult for the FDA to understand, since they typically required that the vaccine be tested on animals first.

Dr. Wu said, “That room was full. It was the first [trial] of this type, and there were people from many different offices. Our argument was, “This is custom, anything we do on an animal doesn’t really match the human, so why go down that route?”

Once they gained FDA approval, six patients with advanced melanoma were vaccinated with a course of seven injections of individualized neoantigen vaccines.

The groundbreaking results, published in Nature in 2017, showed that some of the patients’ immune cells had been activated and their tumor cells had been attacked.

Four years later, a follow-up in 2021 showed that immune responses had worked to keep cancer cells at bay.

Dr Wu said: ‘I am grateful for all the patients who participated in our trial because they are… active partners.

‘It’s hard enough to go through a treatment, but then go through a treatment whose benefit is unknown, and be willing to come in for all the extras we need to do this type of research. There are more tests, more blood draws, more biopsies.’

Dr. Wu and her team, as well as other large pharmaceutical companies such as Merck and Moderna, have delved into cancer vaccine research.

Trials are currently underway for pancreatic and lung cancer.

Dr. Wu said: “I think there are many paths to Rome. I think there are many different delivery modalities, but each delivery approach can be optimized with different details.

‘There has to be investment and how to make that delivery approach work better. And right now there is a huge appetite for mRNA, you know, fueled by our pandemic.”

mRNA vaccines provide instructions to cells to make the right proteins and contain a small piece of a protein from the cancer cell.

Meanwhile, a new class of therapy has been hailed as a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

Similar to cancer vaccines, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) use immune cells from a patient’s tumors to drive a long-term defense.

Last week, the FDA approved a TIL for advanced melanoma called Amtagvi.

It is given as an infusion into a vein in the hospital. The drug works by extracting and then replicating a type of white blood cell called T cells extracted from a patient’s tumor.

Patrick Hwu, CEO of Moffitt Cancer Center, told Axios: “This is the tip of the iceberg of what TIL can bring to the future of medicine.”