Nemo and his clever clownfish companions can count to determine whether other fish are friends or foes, a new study has revealed.

Researchers say these territorial, feisty fish distinguish between threatening intruders and harmless cohabitants by counting the stripes on their bodies.

The scientists tested the orange fish to measure its reaction to fish of the same or similar species with one to three characteristic white stripes.

By keeping count, the researchers discovered that the clownfish counted the stripes of other fish and did not like those with three stripes like them, as well as fish with two stripes.

But those with one or no stripes tended to be left alone.

Nemo and his clever clownfish companions can count to determine whether other fish are friends or foes, a new study has revealed.

Researchers say these territorial, feisty fish distinguish between threatening intruders and harmless cohabitants by counting the stripes on their bodies.

The Japanese scientists behind the study, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, say this is proof of the fish’s impressive counting ability.

Although Pixar would like you to believe that Nemo and his clownfish cohort are shy and welcoming fish, the truth is far from that.

They are actually feisty little creatures that eagerly defend their anemone homes from intruders.

And while it is sometimes okay for fish to share their habitats with anemone fish of other species, it is rarely, if ever, acceptable to cohabit with intruders of their own species, who receive particularly frigid receptions.

According to the researchers, species that live in the same places tend to have a wide range of striping patterns, from three vertical white bars to none.

Previous studies have shown that coral reef fish, including clownfish, develop their stripes so that other fish can find them in a crowd.

But researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology set out to decipher how anemone fish distinguish members of their own species from other similarly striped fish.

Dr. Kina Hayashi and his colleagues raised a school of young Nemos (or common clownfish) from eggs, to ensure that the fish had never seen other species of anemone fish.

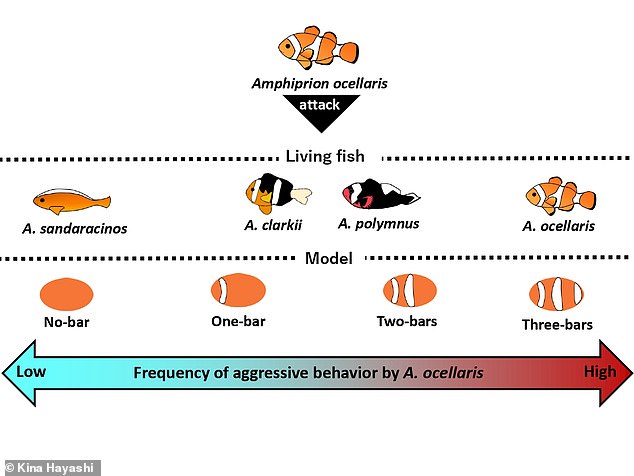

Once the little ones were six months old, Dr. Hayashi began filming their reactions to other species of anemonefish, including Clarke’s anemonefish (A. clarkii), orange skunk clownfish (A. sandaracinos), and saddle clownfish (A.. polymnus), as well as intruders of their own species.

As expected, the common clownfish gave the most difficulty to members of its own species with three white bands like them; engaging four-fifths (80 percent) of the fish for up to three seconds and even holding an 11-second standoff with one fish.

The researchers isolated small schools of three young common clownfish in individual tanks and filmed their reactions to an orange fish model or models painted with one, two, or three white bands, keeping a count of how often the fish bit and tried to bite. drive away. the offending intruder

The researchers found that the young clownfish paid little attention to the simple orange model, similar to the lack of interest they had shown in the orange skunk clownfish, and simply occasionally nibbled and chased the model with a single rod.

In contrast, the researchers found that intruders from other species had it easier.

The orange skunk clownfish, which has no side bars but rather a white line along its back, came out the lightest and was barely confronted.

Meanwhile, Clarke’s clownfish and saddleback clownfish, which boast two and three white bars, respectively, were mildly intimidated.

“The common clownfish attacked its own species more frequently,” Dr. Hayashi observed.

But it remained a mystery to scientists how the clownfish distinguished between members of its own species and others.

In another series of tests, the researchers isolated small schools of three young common clownfish in individual tanks and filmed their reactions to an orange fish model or models painted with one, two or three white bands, keeping a count of the frequency with the that the fish bit and tried to scare away the offending intruder.

They found that the young clownfish paid little attention to the simple orange model, similar to the lack of interest they had shown in the orange skunk clownfish, and simply occasionally nibbled and chased the model with a single rod.

However, they upped the ante again with the three-stripe models, showing how little they liked sharing space with three-striped strangers who looked like them, while the two-stripe model also received a rather unpleasant reception.

Dr. Hayashi suggested that clownfish’s aversion to fish with two bars could be related to their development.

The common clownfish initially forms two white stripes around 11 days of age, before gaining the third three days later.

Therefore, Dr. Hayashi suspects that clownfish that grow up with other two-striped juveniles might see fish with two white bars as competitors to chase away.

Therefore, the researchers’ study shows that young common clownfish living in anemones can distinguish between species that pose a threat and those that do not based on the number of white bars on the sides of the fish.

This allows them to defend their abode from intruders who might try to evict them, while paying less attention to fish of other species that have little interest in taking up residence in their anemone residence.