Ready meals, frozen pizza, soft drinks and even supermarket bread could age faster, alarming new research suggests.

Italian researchers have discovered that people who eat more ultra-processed foods (UPF) have greater signs of biological aging.

Biological aging is a scientific term to refer to the age of the cells and tissues in your body, depending on how they function.

This may differ from your chronological age: the number of birthdays you have had.

In the new study, which examined the diet and biological age of just over 22,000 Italian adults, experts found that those who ate the most UPF were about four months onwards biologically older than their chronological age.

In contrast, those who ate less UPF were found to be on average two months younger than their biological age.

While the difference is small, the findings raise growing concerns that high UPF consumption is linked to health problems such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer and death.

The authors, from the Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Neuromed, said their study did not establish exactly how UPFs could accelerate aging.

Ready meals, frozen pizza, soft drinks and even the humble supermarket bread could age faster, alarming new research suggests. (File image)

In the new study, which examined the diet and biological age of just over 22,000 Italian adults, experts found that those who ate the most UPF were about four months older than their actual chronological age.

But they added that, after taking into account the participants’ overall diet, aging could not be explained solely by the fat, sugar and salt content in UPF.

Instead, they suspected that another factor related to UPF could be the explanation behind the increase in aging.

Simona Esposito, an epidemiology expert and lead author of the study, explained: Our data show that a high consumption of UPF not only has a negative impact on overall health, but could also accelerate aging itself, suggesting a connection. that goes beyond the poor. nutritional quality of these foods.’

The authors suggested two possibilities that could explain how UPFs could be related to biological aging.

The first is that UPFs tend to have a higher content of acrylamide, a neurotoxic chemical that forms when foods are processed at high temperatures.

They cited research linking high exposure to acrylamide with an “increased oxidative stress and inflammation”, which are believed to be precursors to some of the leading causes of death in the UK.

The second is that UPFs are usually wrapped in plastic.

This means UPF consumers could be at risk of packaging chemicals leaching into their food and potentially consuming it.

While many UPF-free foods are also wrapped in plastic, the authors theorized that because UPFs tend to have a longer shelf life, there is more time for the chemicals to leach into the food.

Marialaura Bonaccio, nutritional epidemiologist and co-author of the study, stated: “These products are usually wrapped in plastic packaging, thus becoming vehicles for toxic substances for the body.”

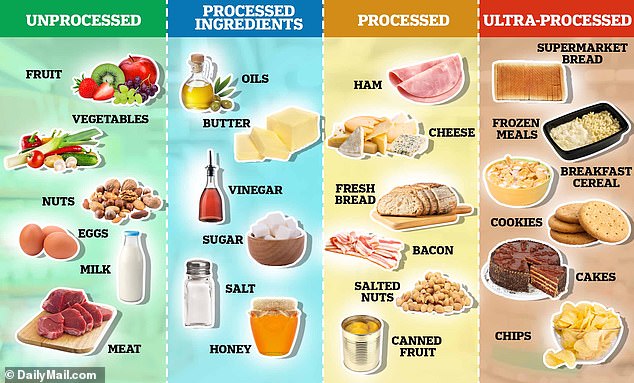

UPF is a staple of the modern British diet and is an umbrella term that covers a host of foods full of artificial colours, sweeteners and preservatives that extend shelf life.

Another author of the study, Professor Licia Iacoviello, director of the epidemiology and prevention research unit at Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Neuromed, said her study adds to calls for more to be done to warn consumers about UPFs.

“This study leads us once again to reevaluate current dietary recommendations, which should also include warnings about limiting the intake of ultra-processed foods in our daily diet,” he said.

The authors, who published their study in The American Journal of Clinical NutritionThey reached their conclusions after examining dietary data and biological markers of aging from 22,495 Italian adults.

Biological markers of aging included signs of inflammation in the body, as well as metabolism and organ function, all measured by blood tests. These data were used to calculate the biological age of each participant.

The researchers then compared this data to the amount of UPF the participants consumed based on the questionnaires and identified patterns.

The study had a number of limitations, which the authors acknowledged.

First, the study is observational, meaning that researchers cannot be sure that UPF consumption is behind the increase in biological aging, and not some other factor.

The second was that participants’ dietary information was collected using a questionnaire, meaning people could be wrong in reporting how much UPF they consumed.

UPFs cover a lot of foods and beverages full of artificial colors, sweeteners and preservatives, plus, typically, calories and sugar.

Examples include ready meals, ice cream, and even ketchup.

They typically undergo multiple industrial processes that research shows degrade the physical structure of food, making it faster to absorb.

This, in turn, can increase the risk of blood sugar spikes and spikes, which reduces satiety.

It has also been said to damage the microbiome, the community of “friendly” bacteria that live inside us and that we depend on for good health.

UPFs are believed to be a key driver of obesity, which costs the NHS around £6.5 billion a year.

However, experts have repeatedly urged caution when linking UPF consumption to health problems.

Many consider the term UPF to be too broad, considering that a loaf of whole wheat bread, which has some health benefits, and a prepared meal rich in salt, fat and sugar, are the same type of food according to their system of classification.

Some experts argue that this can make it unclear which UPFs might be causing specific health problems.

Researchers have also highlighted that UPFs themselves may not be directly causing the health problems seen in the studies.

Instead, they suggested that eating a lot of UPF could be a symptom of other problems such as poverty, which can reduce people’s intake of fresh fruits and vegetables.