NASA has identified a gas on Mars produced by living creatures on Earth, puzzling scientists about what could be hiding on the Red Planet.

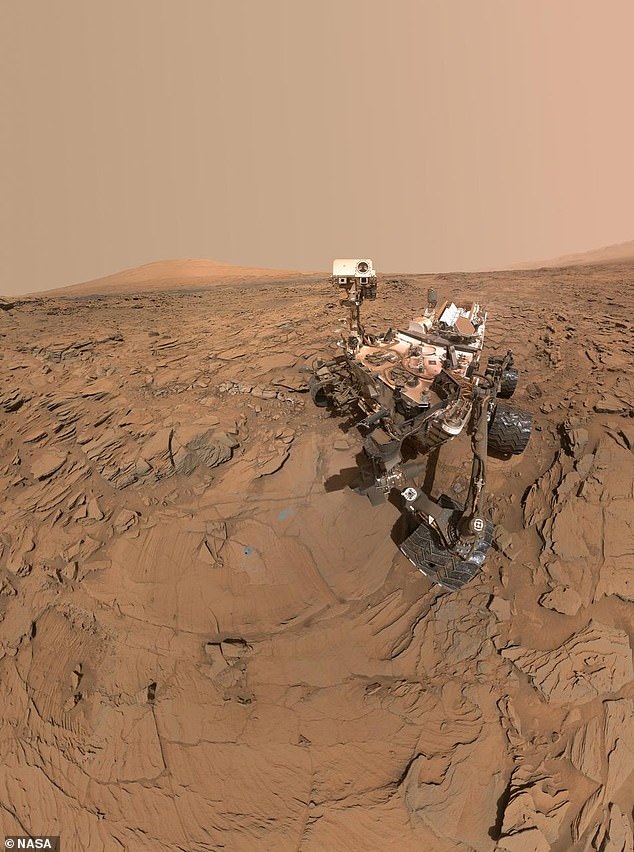

The Curiosity Rover detected a constant flow of methane coming from Gale Crater, which appears at different times of the day and fluctuates seasonally, sometimes reaching 40 times more than usual.

While NASA has yet to find life on the Martian world, scientists believe the source comes from deep within the earth.

The team has suggested that the methane could be locked under solidified salt and only leak out when temperatures rise on Mars, or when Curiosity rolls over the crust and breaks it up.

On Earth, this simple molecule, made up of one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms, is often a sign of life: the gas that animals expel while digesting food.

NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover detected methane coming from near Gale Crater, but not all the time. Scientists wanted to know why.

Scientists used this sample of Mars soil to conduct an experiment on how a crust forms, trapping methane beneath the planet’s surface during the day.

NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover has been roaming the surface of Mars since 2012, and in all that time, the most disconcerting thing it encountered was a steady stream of methane coming from Gale Crater.

The spot in Gale Crater where the methane came from was the only place on the planet where Curiosity detected the gas.

But Curiosity has not detected cows on Mars, nor has it found people who have eaten a large helping of cabbage.

In laboratory experiments that mimic Martian soil conditions, scientists were able to simulate what could be happening.

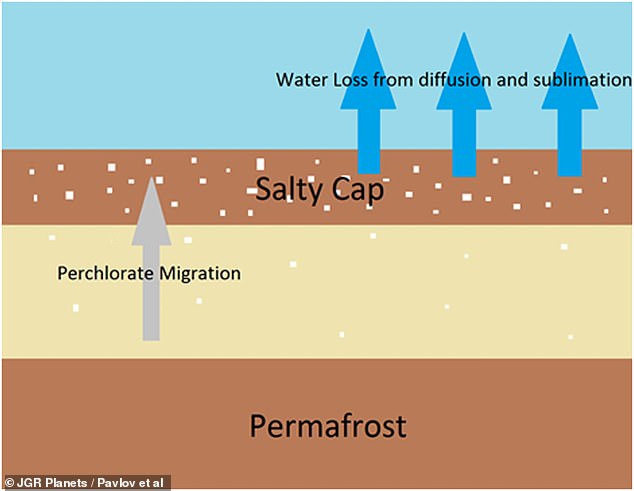

For a long time, salts, a substance known as “regolith,” have been bubbling up from deep within the planet’s rocky, dusty surface.

These salts are called perchlorates and they are abundant on Mars.

Perchlorates, which are toxic, are abundant in ice trapped beneath the planet’s surface.

As happens with ice when there is very little atmosphere, this ice gradually evaporates. And as this salty vapor seeps through the regolith, it leaves a bit of itself behind.

Perchlorate salts trapped in Mars permafrost evaporate and become trapped in the soil. There it forms a crust that traps methane below the surface during the day.

When the team bubbled salty vapor through the simulated regolith of Mars, it created this crust that could trap gas.

When enough of these salts accumulate in the regolith, they form a kind of shell, like beach sand when it dries into a brittle crust, or like the disk of coffee grounds left after taking a shot of espresso. .

“On Mars, such a process can occur naturally over a long period of time in the shallow regions of permafrost, and it is possible that enough salt accumulates in the upper layer to form a seal,” wrote the scientists behind the new studywhich was published in the magazine JGR Planets.

At the same time that the salty vapor bubbles, so does the methane.

Its origin remains a mystery.

It could be due to some type of living being, or it could be due to geological processes beneath the planet’s surface, still invisible to human scientists.

Wherever it comes from, it ends up trapped under this crust of salt.

By pumping different concentrations of perchlorates through the simulated Mars regolith, the scientists found that three to 13 days was enough time for this impermeable crust to form.

The rocky floor surface of Gale Crater traps methane beneath, but Curiosity may be releasing it when it breaks through the crust.

Curiosity is the only NASA spacecraft that has detected methane on the planet. It has not been detected in the atmosphere of Mars.

A perchlorate concentration of 5 to 10 percent was also required to create a solid salt crust.

They pumped neon gas beneath the crust, as a substitute for methane, confirming that the layer was strong enough to trap gas beneath.

But then, when the planet’s temperature rises during certain hours of the day or certain seasons, this crust breaks down, letting out the methane.

And that’s when Curiosity would detect methane in the air.

However, it is not just the temperature that can break the crust.

The crust is probably about two centimeters thick, a little less than an inch. And Curiosity is heavy enough to roll through it, the team behind the study wrote.

“To test this hypothesis, it would be beneficial to take methane measurements when the rover reaches a location with abundant salt content (such as salt veins),” they wrote. “Another test would be to try to ingest Martian air while drilling into the salt-rich surface.”

NASA has not yet conducted such an experiment.