Scientists have taken another step toward preserving our brains forever.

They are one of the first to successfully thaw cryogenically frozen brain tissue, without damaging it.

Furthermore, after being frozen, their neurons could still send signals normally.

This has been a big challenge for science, because freezing the ultra-delicate, spongy brain usually damages it, making it useless when thawed.

Not only is this a breakthrough for neuroscientists looking to study new drugs, but it could also promote the science fiction idea of bringing people back to life in the future.

Many celebrities have said that they hope to freeze their bodies when they die, in case they can reanimate their brains in the future.

The oldest patient at the Cryonics Institute, named Rhea Ettinger, has been there since 1977. The number of people stored at the Michigan institution has more than tripled since 2006.

The idea is that people can freeze their bodies, preserving them indefinitely, in the hope that in the future science will advance enough to bring them back to life and healthy.

Professor Zhicheng Shao, a Harvard-trained neuroscientist working at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, developed a complex chemical mixture called MEDY that protects neurons from damage while frozen.

He doesn’t shy away from the idea that the research could be used for cryonics, which has been a fantasy among futurists for decades.

“MEDY could be used for cryopreservation of human brain tissue,” Dr. Shao said in his study, published in the journal Cellular reporting methods.

For a variety of forward-thinking people, from people like Peter Thiel to Steve Aoki, who swear by preserving their bodies on ice after they die, this should be good news.

It’s just that, as Thiel acknowledged in a 2023 interview, we still don’t know how to make cryopreservation work, for the body in general and the brain in particular.

That certainly hasn’t stopped companies from taking advantage of the hype. Since the mid-20th century we have been enjoying the cryo-renaissance, with laboratories springing up in Michigan, Arizona and Australia.

At Michigan-based Cryonics Lab, full-body preservation starts at $28,000, and its clientele has more than tripled since 2006, now numbering more than 1,975 permanent residents.

Each cryonics industry has its own mixture that they say preserves the brain and body, but scientists have not concluded that there is a safe way to protect the brain when frozen.

Since 80 percent of our brain cells are made of water, when we freeze them, ice crystals sometimes form.

These can distort and damage all of our cells, but especially delicate brain cells, rendering them functionally useless when they thaw.

So, Professor Shao and his team set out to find a different substance to immerse the brain tissue that would keep it cold, preventing it from aging, without having problems with the crystals.

You could think of it as adding antifreeze to the water circulating around your car’s engine, keeping it cool without freezing.

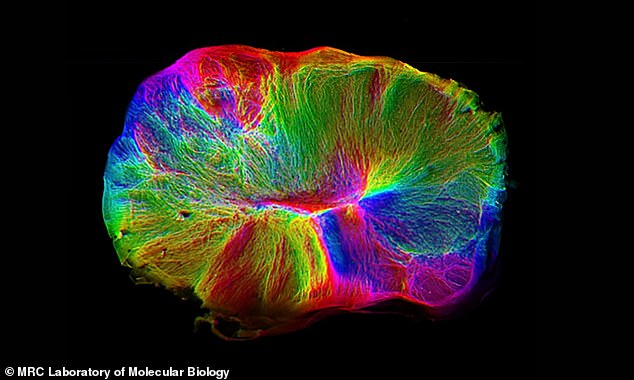

To do this, Professor Shao and his team cultured small groups of brain cells in Petri dishes for three weeks, until they obtained the functions that would be seen in a normal brain, only in miniature form.

They then soaked these tiny brains, called organoids, in different mixtures, including sugar, antifreeze and chemical solvents.

After saturating the samples, they were flash frozen with liquid nitrogen and then allowed to thaw over the next two weeks.

As the samples thawed, scientists watched to see which samples recovered with the least amount of damage.

The tiny organoid, about the size of a lentil, was created from connected human brain cells for a 2019 study.

A cryonics facility located next to Holbrook Cemetery, New South Wales, Australia. Spaces in this freezer cost around $150,000.

Because the brain is made up of 80 percent water, freezing it can cause ice crystals to form in the tissue, damaging the cells and rendering them useless when they thaw.

After some trial and error, they created a mixture they call MEDY – after its four ingredients: methylcellulose, ethylene glycol, DMSO and Y27632 – that allows them to freeze tissue without damaging it.

The brain tissue was not only unharmed, but also brought back to life, able to regain normal function.

In the future, if we wanted to learn to do this with the whole body, we would have to be able to cure what originally killed a person and reverse aging, Dennis Kowalski, president of the Cryonics Institute, told Discover magazine.

Dr. Kowalksi, who describes himself as an optimist, acknowledged that this is clearly “not 100 percent possible today.”

Professor Shao’s mixture is not the first substance that has successfully protected a brain before freezing it. Other freezing processes have shown promise, but present their own problems.

One popular method, which had great success in pig brains, involves pumping embalming fluid into the brain while the person is still alive. This not only kills the subject, but makes it impossible to revive the brain later, says neuroscientist Dr. Ken Hayworth of the Brain Preservation Foundation. he told CNET.

“It binds all the proteins in the brain almost instantly,” Dr. Hayworth said.

In the near future, Professor Shao wrote that the MEDY technique will probably be useful only for the laboratory.

But there are many things we can do with brains frozen in a laboratory.

Being able to freeze these mini-human brains means that more tissue will be available for researchers to test new drugs and therapies, Professor Shao wrote.

This could help us make progress in a number of difficult areas of medicine, said Dr. Takanori Takebe, a pediatrician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. said in a 2018 article.

“Organoids hold great promise for revolutionizing 21st century healthcare by transforming drug development, precision medicine, and ultimately transplant-based therapies for terminal illnesses,” said pediatrician Dr. Takanori Takebe. from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. said in a 2018 article.

In the more distant future, Professor Shao wrote that MEDY has the potential to freeze the entire brain. But that comes with its own challenges, because going from freezing an organoid to a complete organ, like the brain, is complicated for several reasons.

Organoid research, in general, is a great way to understand how certain types of cells act.

But it’s not always effective at predicting how an entire organ would respond to new stimuli, since what’s on the plate is much less complex than what’s in our bodies, researchers at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine at the University of California wrote in 2023.

Furthermore, the University of California researchers wrote, these organoids simply “do not reflect the entire composition, organization, or function of the human brain.” Therefore, it is difficult to know whether the way we freeze the organoid will translate to the entire brain.

Furthermore, even if we can successfully freeze a brain without damaging it, there will be a whole new set of challenges in thawing and reanimating it, because we currently know so little about the brain, said Dr. Ken Miller, a theoretical neuroscientist at Columbia University. , he told CNET.

‘The most basic answer about how the brain works is: we don’t know. “We know how a lot of the pieces work… but we’re a long way from understanding the system,” Dr. Miller said.