From lost cities beneath the waves to vast jungle ruins, the ancient world is full of enticing mysteries in remote places.

But the latest discovery that baffled archaeologists was found much closer to home: in the small town of Norton Disney, just outside Lincoln.

A strange Roman object, believed to have been buried about 1,700 years ago, has 12 sides, each with different sized holes and small spheres attached.

This enigmatic copper object is one of 33 dodecahedra found in the UK and, at 8cm (3in) high and weighing 245g, is one of the largest ever found.

However, while theories suggest it could be anything from a crochet tool to an elaborate die, the object’s actual use may be lost over time.

This strange 12-sided Roman object has baffled archaeologists, but do you think you know what it is?

The object was found in the village of Norton Disney, the home of Walt Disney’s ancestors, and is one of 33 Roman dodecahedra found in Britain.

The object was unearthed by volunteers in the summer of 2023 by the Norton Disney Archaeological and Historical Group.

The dodecahedron later appeared in a recent episode of the BBC program ‘Digging for Britain’.

In the episode, Professor Alison Roberts said: “It has to be one of the largest and most mysterious archaeological objects I have ever had the opportunity to look at up close.”

Experts believe the mysterious object may date back to the 1st century AD, during the early days of the Roman occupation.

Each side of the hollow metal object contains a hole of different sizes with a round ball attached to each corner.

These unusual features have led to a host of unusual suggestions as to what these strange objects might actually have been used for.

Some suggest that these 12-sided objects could have some link to Roman religious practices, but Roman texts do not mention these strange objects.

Dr Jonathan Foyle, an archaeologist at the University of Bath, said BBC that many seemingly obvious suggestions do not stand up to closer examination.

With its 12 uniform sides, some have suggested that the device could have been used as a dice in some type of Roman game.

Measuring 8cm (3in) high and weighing 245g, this is one of the 33 largest Roman dodecahedra discovered in the UK.

The object is now on display at the Lincoln Museum (pictured), where it will be open to the public until September.

However, Dr Foyle says: “There are other sizes of dodecahedron that could be more portable if the military were on the move.”

‘They don’t have any numbers, so you can throw them [as dice].’

Despite being made of metal, Dr. Foyle also notes that the object is surprisingly fragile.

The fact that it is still in one piece after almost 2,000 years suggests that it was more likely to have been carefully cared for rather than used for games.

Another popular theory suggests that these objects were weaving tools, used to make fingers for gloves.

Several modern knitters have even created tutorials on how to use plastic replicas of Roman dodecahedra to produce wearable clothing.

They suggest that by anchoring the thread in the corner balls, a tube of material can be woven and passed through the holes in each face.

Using each of the holes, knitters have shown that tubes of different sizes can be made, perfect for creating well-fitting gloves.

However, Dr Foyle says: “You can actually make a glove finger out of them, something people have done ingeniously.”

But, for the Romans, “there was no evidence of weaving until centuries later.”

The artifact recently featured on an episode of the BBC’s Digging for Britain in which Professor Alice Roberts examined the strange object up close.

Lincolnshire, where the object was found, was the site of several Roman settlements and is home to several archaeological sites and Roman ruins (pictured)

Other theories also suggest that the different holes could have been used as a way to measure standardized objects such as shot or spears.

In response to a suggestion that the device could have been used as an ancient pasta measuring tool, Dr Foyle points out that this staple dish did not emerge until long after the fall of the Roman Empire.

“While the Romans had to wait centuries for pasta, they ate dormice in fish sauce,” he adds.

Similarly, Lorena Hitchens, a PhD candidate at Newcastle University who is studying the object, says she does not believe the object was used for measurements at all.

In a post on her website, Ms. Hitchens writes: “I don’t think dodecahedra were useful for knitting gloves, sizing spears, or making measurements.”

She explains: “Virtually all theories about tools or other utilitarian functions are quickly ruled out because of the variation of dodecahedra.”

“Since there was no standardization between them, they would not have been effective for measurement.”

This object was discovered by a team of volunteers (pictured) who plan to return to the site this year for further studies.

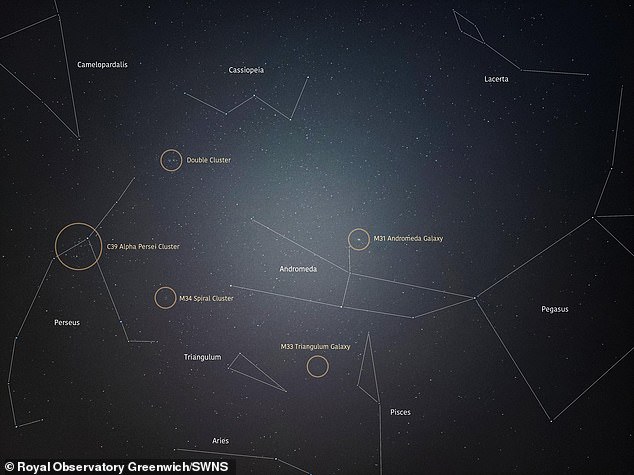

One theory suggests that the object could have been used to “frame” constellations (pictured). By looking through the holes, the viewer could have framed a view like a modern camera operator.

While no theory has yet been confirmed, Dr. Foyle believes the most likely answer is that the object was used for stargazing.

Dr. Foyle says: “What I think it is is a device for framing the constellations of the zodiac.

“If you look through them, you can frame a view, much like a camera operator.”

A dodecahedron found in Switzerland even includes the names of the zodiac on each of the faces.

However, Dr Foyle also believes that the object may not have been created by the Romans themselves but by the “people we call Celts”.

The Romans may have influenced native metal craftsmen with their ideas of a 12-sided universe as described by Plato, which could have led them to make objects for their own use.

“They are not found in the Mediterranean, in the center of the Roman empire, nor in the unconquered Celtic lands,” explains Dr. Foyle.

For those who want to take a closer look, the object will be on display until September at the Lincoln Museum.