A notorious California prison, known as the ‘rape club’ by inmates and the ‘feeding club’ by famous inmates like Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin, will be closed after years of rampant sexual abuse by staff against female prisoners.

Some of the inmates at FCI Dublin, located about 21 miles east of Oakland, were already being transferred to other prisons on Monday when Federal Bureau of Prisons officials announced plans to close the facility.

Bureau of Prisons Director Colette Peters confirmed to DailyMail.com that the agency took “unprecedented steps and provided an enormous amount of resources to address culture, recruitment and retention, aging infrastructure and, most critically, employee misconduct.

“Despite these measures and resources, we have determined that FCI Dublin is not meeting expected standards and that the best course of action is to close the facility,” Peters said. “This decision is made after continued evaluation of the effectiveness of these unprecedented measures and additional resources.”

FCI Dublin, located in the Bay Area, has been plagued for years by rampant sexual abuse by staff against female prisoners.

‘Desperate Housewives’ actress Felicity Huffman has completed her time in prison for her role in the college admissions scandal at the campus in Dublin, California.

‘Three by Three’ actress Lori Loughlin also served two months in federal prison in California in connection with the college admissions scandal.

A judge had appointed a special master to oversee reforms at Dublin’s FCI after an explosive investigation in 2021 revealed prison staff were having sexual relationships with inmates, including former warden Ray Garcia.

Sex between a prison worker and an inmate is illegal because prison employees could use their position of power over the wards.

So far, at least eight FCI Dublin employees have been accused of abusing inmates since 2021.

Former Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss, who served three years on charges of tax evasion and money laundering at FCI Dublin from 1997 to 2000, told DailyMail.com it was common knowledge that guards had sex with prisoners.

Fleiss said she was shocked by the prison’s closure, but was not surprised that sexual abuse of inmates continued years after she served her sentence in Dublin because “everyone knew it was happening all the time.”

“When I was there, there were inmates eating Kentucky Fried Chicken,” Fleiss told DailyMail.com on Monday. “And you knew right away that they were screwing with the guards because that fried chicken definitely didn’t come from the prison menu.”

Former Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss told DailyMail.com that sexual relations between prisoners and guards were common during her time in Dublin.

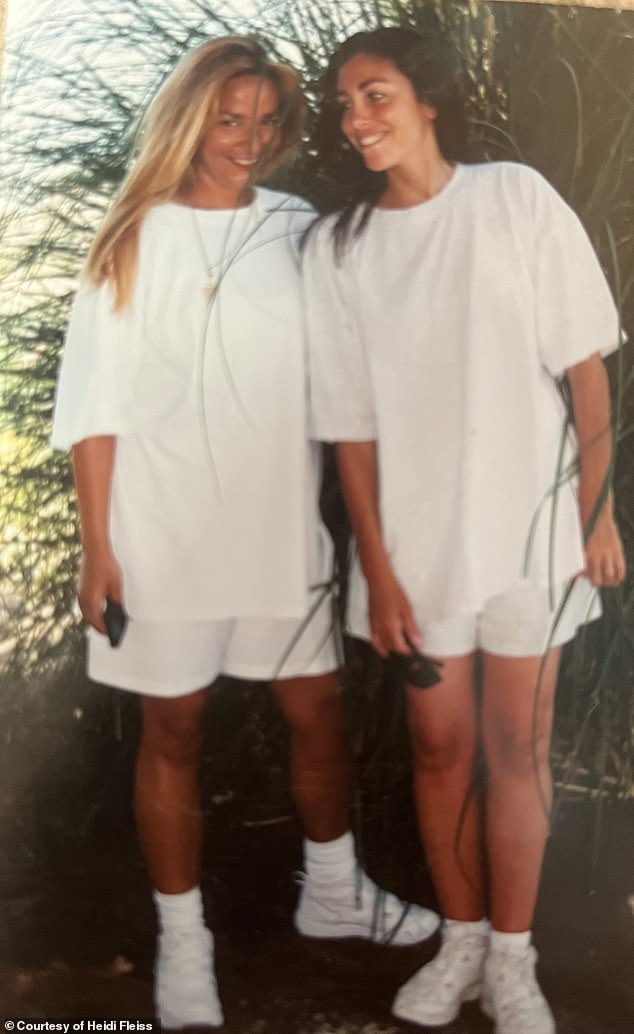

Heidi Fleiss is pictured with her girlfriend ‘Sylvia’, both inmates at FCI Dublin in 1999.

“I remember one woman said to me, ‘Hey, look at this,’ and then she showed me her lingerie while she ate her KFC.

“All I said to her was, ‘Oh, that’s cute,’ but what I really thought was, ‘None of my girls had to fuck to get fried chicken!’

Fleiss said she initially spent four months of her time in the facility’s medium-security camp, which is known as a “fed club” area where other famous inmates such as Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin served their time for their roles in the scandal. of college admissions.

But after throwing a chair at a guard, Fleiss said she was sent to the “big house” in Dublin, where she saw moldy carpets and dilapidated cells.

During her three years in Dublin, Fleiss said one of her former fellow prisoners began having sexual relations with a prison guard called ‘Hyson’, known to all the inmates as a charming flirt.

That former prison guard, Jon C. Hyson, was ultimately charged with 17 counts of sexual relations with inmates and five counts of lying to investigators. He was accused of asking two inmates to perform a sexual act on each other and allegedly received oral sex from an inmate.

He was also accused of engaging in 14 sexual acts with at least two inmates and lying to Justice Department investigators.

Former Dublin FCI director Ray Garcia, left, was convicted in 2022 and sentenced to nearly six years in prison for sexually abusing three inmates and lying to federal officials about it.

“My friend was having sex with Hyson and he was bringing her candy,” Fleiss recalled. “But when she found out he was having sex with other inmates, she got angry.”

Hyson pleaded guilty in 1999 to four counts of unlawful sexual acts, one count of attempting to engage in a sexual act and one count of making a false statement to the FBI, according to the San Francisco Gate.

Fleiss said that during his stay in Dublin, the prison was “bursting at the seams” and was overcrowded with around 2,400 inmates.

She remembered a time when she had to share her small cell with three other women.

“I remember asking them if I could use the bathroom and if I could have some privacy,” Fleiss said. And one of them said, ‘Do you think you’re fucking special?’ You need to shit in a Ziploc bag, or you sit on that toilet now and take that shit.”

Fleiss added: “I almost started crying. There were many times I felt afraid for my life because I was there with murderers.’

Fleiss said some of the prisoners traded sex for Kentucky Fried Chicken, which guards brought into the prison.

A typical Dublin FCI cell, scheduled for closure due to rampant sexual abuse of prisoners and mold and asbestos found in the facility.

Bureau of Prisons officials said inmates will be transferred to other prisons, while staff will keep their jobs.

Fleiss said that in addition to married prison guards having affairs with inmates, there was also a suicide and a prison escape during their time in Dublin.

“There were a lot of evil women there – believe me, they were really evil,” Fleiss told DailyMail.com. “I didn’t know all of them, but some of them should never have been let out.”

While Dublin appears less crowded since Fleiss’s time, prison officials have yet to find a place to move its 605 inmates.

BOP officials did not confirm which other prisons the women will be transferred to for safety reasons.

The official last day that Dublin must close its doors is still unclear, but BOP officials said no current employees will lose their jobs.

Meanwhile, the agency still faces lawsuits from eight inmates, who claim prison officials did nothing to stop sexual abuse for years.

Amaris Montes, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, said her clients continued to face retaliation.

“I think the BOP is rushing to try to shift responsibility and shift it somewhere else as a way to remedy the problem,” the attorney told the Associated Press. “And that would mean, you know, moving people quickly without addressing their needs right now.”