Maine mass shooter Robert Card was suffering from traumatic brain injuries when he unleashed a massacre that killed 18 people in the state’s worst gun tragedy.

The damage was likely caused by recurring exposure to explosions at the Army hand grenade training range where the reservist worked, according to an analysis of brain tissue by Boston University researchers that was published Wednesday.

There was degeneration in the nerve fibers that allow communication between different areas of the brain, inflammation and injury to small blood vessels, according to Dr. Ann McKee of Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center. The analysis was published by Card’s family.

“Although I cannot say with certainty that these pathological findings underlie Mr. Card’s behavioral changes in the last 10 months of life, based on our previous work, the brain injury likely played a role in his symptoms,” McKee said. in the family statement.

Card’s family members also apologized for the attack in the statement, saying they are heartbroken for the victims, survivors and their loved ones.

That soldier, the platoon member said, was eventually removed from the training ground with grenades, where both he and Card, pictured above, were almost always stationed.

Body camera video of police interviews with reservists before Card’s two-week hospitalization in upstate New York last summer also showed other reservists expressing concern and alarm about his behavior and weight loss.

Card killed 18 people at a bowling alley and a restaurant and bar in Lewiston

In November, Louisville Metro Police released a report saying they found no evidence that Card suffered from CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which is caused by repeated blows to the head.

Card’s parents had said they wanted him to have a brain test for CTE because he had suffered many concussions as a high school athlete.

Army officials will testify Thursday before a special commission investigating the deadliest mass shooting in Maine history.

The commission is reviewing the facts surrounding the Oct. 25 shootings that killed 18 people at a bowling alley and a restaurant and bar in Lewiston. The panel, which includes former judges and prosecutors, is also reviewing the police response to the shootings.

Police and the military were warned that the shooter, Card, was suffering from deteriorating mental health in the months before the shooting.

Some relatives of Card, 40, warned police that he was exhibiting paranoid behavior and were concerned about his access to weapons. Body camera video of police interviews with reservists before Card’s two-week hospitalization in upstate New York last summer also showed other reservists expressing concern and alarm about his behavior and weight loss.

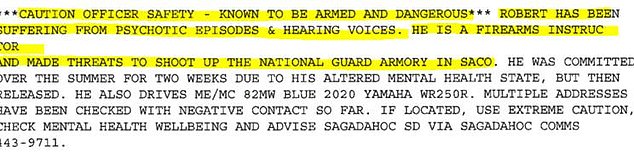

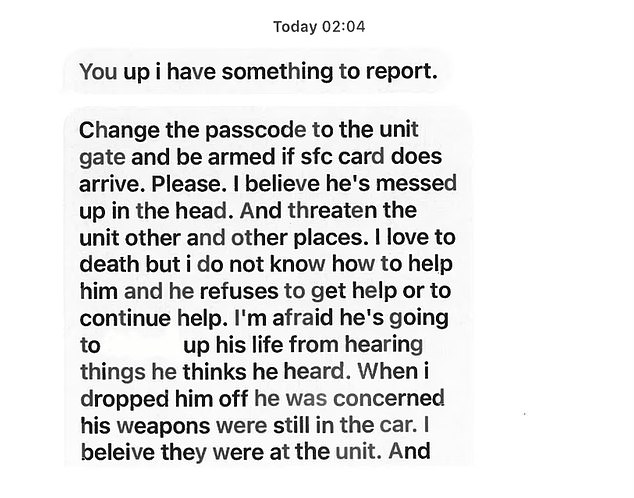

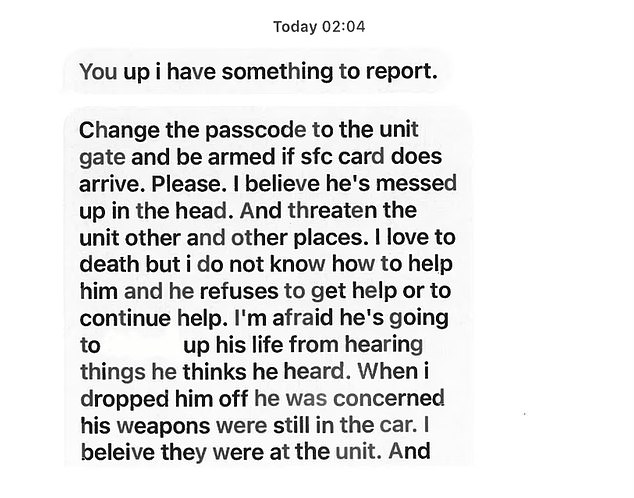

This is the alert all Maine police departments received about Robert Card in September. Two attempts were made to contact him and security was added to the military base, but it was canceled on October 18.

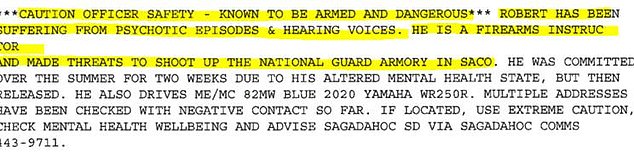

These text messages sent by an Army reservist sergeant to his supervisor in September reveal the extent to which there were concerns about Robert Card. The supervisor called the police, who issued an alert about Card, but nothing was done to arrest him or take away his weapons.

A body is carried out on a stretcher at Schemengees Bar and Grille in Lewiston, Maine

Card was hospitalized in July after shoving a fellow reservist and locking himself in a motel room during training. Later in September, a fellow reservist told an Army superior that he was worried Card was going to “break out and do a mass shooting.”

In his diary entries, Card wrote about his desire to make a difference with shooting and impact weapon laws, and mentioned that it was easy for a “psychopath” like him to buy a firearm.

The shooter was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound after the largest search in state history. Victims’ families, politicians, gun control advocates and others have said in the months since the shootings that law enforcement missed several opportunities to intercede and remove Card’s guns. They have also raised questions about the state’s mental health system.

Thursday’s hearing in Augusta is the seventh and last currently scheduled for the commission. Commission chairman Daniel Wathen said at a hearing with victims earlier this week that an interim report could be released by April 1.

The 18 victims of the Lewiston mass shooting

Wathen said during the session with victims that the commission hearings have been instrumental in unraveling the case.

“This was a great tragedy for you, unbelievable,” Wathen said during Monday’s hearing. “But I think it has affected everyone in Maine and beyond.”

In previous hearings, law enforcement officials defended the approach they took with Card in the months before the shootings. Members of the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office testified that the state’s yellow flag law makes it difficult to take guns away from a potentially dangerous person.

Maine Democrats are seeking to make changes to the state’s gun laws in the wake of the shootings. Mills wants to change state law to allow authorities to go directly to a judge to request a protective custody order to detain a dangerous person and take away their weapons.

Other Democrats in Maine have proposed a 72-hour waiting period for most gun purchases.