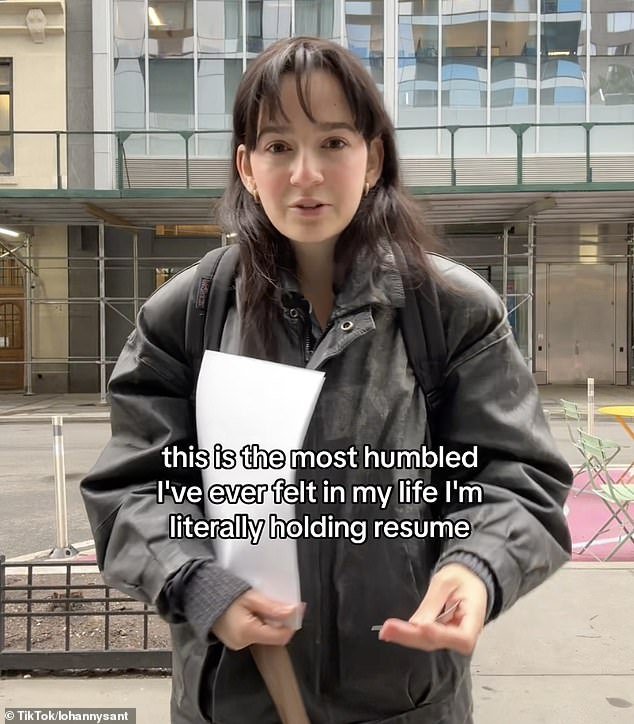

A crying Gen Z job seeker with two degrees and three languages has said she is the “most humble” after going door-to-door for a minimum wage job and going on strike, adding that “she just wants to be a TikTokker.”

Lohanny Santos, 26, from Brooklyn, uploaded a video of herself crying while holding a stack of resumes to TikTok.

“This is the most humbled I’ve ever felt in my life,” he said, telling viewers that he was trying to meet potential employers in person to ask them for a job, but so far has been unsuccessful.

He added: “Honestly, it’s a little embarrassing because I’m literally applying for minimum wage jobs and some of them say ‘we’re not hiring’ (…) This is not what I expected.”

Santos, who graduated from Pace University with a bachelor’s degree in communications and a bachelor’s degree in acting, said she speaks three languages and seems devastated after failing to find a minimum wage job that would pay her $16 an hour in New York.

Lohanny Santos (pictured), 26, from Brooklyn, uploaded a video of herself crying while holding a stack of resumes to TikTok.

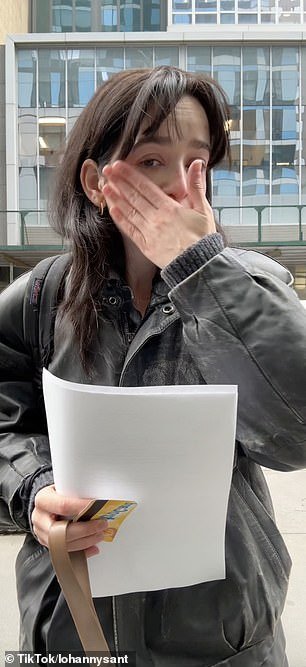

Santos admitted that “this sucks” as he wiped away tears streaming down his face. He said he wouldn’t give up his job search because he “literally needs to make money.”

“This sucks,” she added as she wiped away the tears that were streaming down her face. “I just wanna be a TikTokker if I’m being real with you, but I can’t fool myself anymore… Like I literally need to make money so I’m just going to keep trying.”

Santos isn’t the only one who can’t find work in New York right now, as data from the New York State Department of Labor reveals that unemployment is rising.

New York City’s unemployment rate was 5.4 percent in December, up 0.1 percent from November and up 0.3 percent from December 2022. The New York state rate York was 4.5 percent in December 2023.

Santos’ video seemed to resonate with many Zoomers (colloquial name for members of Generation Z), as it garnered 3.3 million likes on TikTok.

‘Never feel ashamed. You should be proud to put your pride aside and be realistic,” wrote one of his fans.

Another follower said: ‘This is precisely how you apply for jobs before the internet. There’s nothing to be ashamed of as this gives you real-world sales experience.’

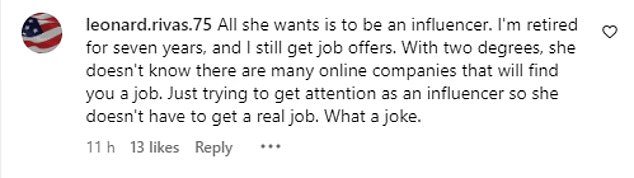

But not everyone sympathized with Santos’ situation.

One commenter wrote: “Maybe if you didn’t major in communications and acting, you wouldn’t be in that situation.”

Another asked: ‘Something tells me you’re doing this for the content?’

Santos, who vowed to “keep trying” while crying (pictured above) is not the only one who can’t find work in New York right now, as data from the New York State Department of Labor reveals that unemployment is increasing.

Although Santos received sympathetic comments from young people in the same situation, she also received a lot of criticism, with some users even accusing her of faking her job search and crying on camera.

Some told him that his degrees and languages alone would not get him a job, as experience was most important to employers.

“This used to be a normal process of finding a job when you have no experience, the only difference is that we did it while we were in college, we didn’t wait until after,” one user wrote.

Others said Santos chose the wrong college majors. “Well, choosing communications and acting is not a good start,” said one.

Another added: “Acting like you’re better than everyone else and then crying while applying for a day job is comical, getting off your high horse must be hard.”

But one Instagram user suggested that it wasn’t Santos’ fault that he couldn’t find work and that it was a problem for his entire generation Z.

“The problem is your generation and everyone else’s perception that you are nothing but problems,” the user said.

‘Businessmen don’t want those things in their offices. I’m sorry, now you’re seeing how your schools failed you.’

Ultimately, Santos’ public job search paid off when she landed her first brand partnership with a birth control pill company.

Some of her followers thought her viral video, which showed her crying on camera with a stack of resumes in her hand, might have been for show.

“This is planned,” one user wrote while another commented: “I have a degree in acting and I can cry on the spot.” I don’t want a real job, I want an easy way out and sponsorships.’

A third accused her of “just trying to get attention as an influencer so she doesn’t have to get a real job.”