Respected broadcaster Jonathan Dimbleby has said the UK law against medically assisted dying is “increasingly unbearable” following the death of his brother from motor neurone disease.

Dimbleby’s brother Nicholas, a celebrated sculptor, died at his home earlier this month aged 77.

Now, as MPs prepare to publish a report on assisted dying on Thursday, Dimbleby urged all political parties to commit to voting freely to change the law on the practice in the next parliament.

He said The Guardian that the current regulations that classify assisted dying as a criminal offense “are as anachronistically cruel as capital punishment”

Mr Dimbleby, a friend of King Charles, said: “The law should be changed so that individuals like my brother, protected by crucial legal safeguards, had the right to die at home at a time of their choosing.”

Respected broadcaster Jonathan Dimbleby has said the UK law against medically assisted dying is “increasingly unbearable” following the death of his brother.

Dimbleby’s brother Nicholas, a celebrated sculptor, died at his home earlier this month aged 77. Here he is shown with the sculpture of him “A Bronze Boy on a Pedestal”.

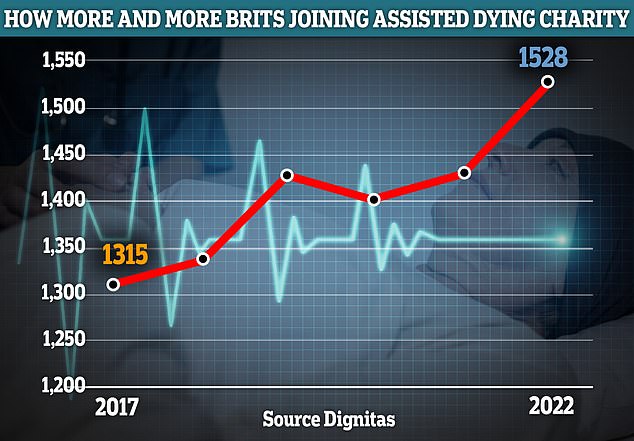

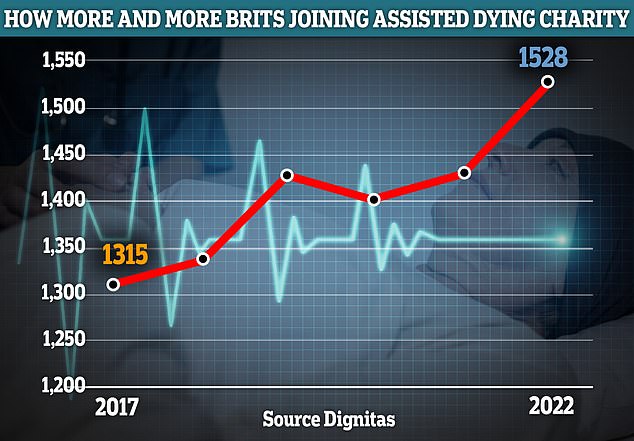

Figures released earlier this year show that as of the end of December 2022, there were 1,528 members of Britain’s Dignitas, according to figures from the charity, which helps dying patients with a “self-determined end of life.” “. . This figure has increased from 821 in 2012. Some 33 people in the UK had an assisted death at Dignitas in 2022, up from 23 people the previous year.

Of his brother he said: “He was a wonderful, strong person, both mentally and physically, and he felt this erosion of life very deeply.”

“He showed immense courage, but as the disease progressed he suffered terrible attacks of asphyxiation although, fortunately, his last hours were peaceful.”

Dimbleby added that, while he respected those who had concerns about assisted dying for moral or religious reasons, politicians had been “misled” by those who said it was always possible to have a painless death and that “evil people” would seek to convince the terminally ill to opt for assisted dying for their own benefit

Before he died, Nicholas himself told Jonathan in a BBC Radio 4 documentary: “I will decide when I will stop… I will say that I will not reduce myself to nothing in a miserable way and I will take control of how I end up.” But I don’t know when that happens. It’s a problem.’

He added that “no one in the business that helps me wants to talk about this, neither in Switzerland nor anywhere else.”

However, following the advice of experts, Nicholas decided that since he would not face a painful death, he would stay and die at home.

Nicholas, whose works include public statues of footballer Jimmy Hill and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) last year.

This rare and incurable disease affects the brain and nerves, inevitably depriving people of their ability to move, eat and, ultimately, breathe.

Mr Dimbleby has direct experience of caring for the terminally ill.

In 2003 he left his wife of 35 years to spend a few final weeks with his dying lover.

His romance with opera singer Susan Chilcott was brief, they had only been seeing each other for a few days before she discovered a lump in her chest that would turn out to be breast cancer.

Dimbleby is not the first public figure to advocate for change.

Late last year, broadcaster Esther Rantzen, 83, announced she was considering assisted dying in Switzerland after being diagnosed with stage four lung cancer.

The public also seems to support the change. A poll in January found that 75 percent of Britons would support making assisted dying legal for terminally ill and sane adults after approval from two doctors. Only 13 percent opposed it.

As public attitudes have changed, so have those of politicians. Labor leader Keir Starmer has said there is a case for changing the law and Education Secretary Gillian Keegan has also said the issue needs to be debated.

Scotland is already proposing its own legalization of assisted dying, which is expected to be debated at Holyrood next year.

Mr Dimbleby’s comments come as MPs on the health and social care select committee are expected to publish the results of a 14-month inquiry into assisted dying tomorrow.

MPs have heard passionate pleas from both sides of the debate.

Critics say assisted dying can be a form of elder abuse and that people could pressure the terminally ill to access their funds or simply relieve themselves of the burden of caring for them.

Many religious groups also oppose any changes, saying it would undermine the value society places on human life.

They have also pointed to legislation in Canada, where people with an incurable medical condition can request to die even if the illness is not terminal, as an example of how far such laws can go.

The country’s law on medically assisted dying is one of the most liberal in the world. Only in approximately 2022

Supporters, however, have warned that the terminally ill have to choose between “suicide, Switzerland or suffering” and that future generations will be “horrified” by current legislation.

Mr Dimbleby, a friend of King Charles, said: “The law should be changed so that individuals like my brother, protected by crucial legal safeguards, would have the right to die at home at a time of their choosing.” The couple photographed here in 1994.

Dame Esther Rantzen, 83, was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer last year and has since revealed she joined assisted dying clinic Dignitas in Switzerland.

UK charities estimate that one Briton travels abroad for assisted dying every eight days.

They have repeatedly warned that Britons are voting with their feet and those with means traveling abroad to countries where assisted dying is legal.

But this leaves those who cannot afford the thousands of pounds the process of taking their own life can cost at home.

This, they add, can cause people to experience pain and suffering when dying, compared to a painless, medically assisted death.

Medically assisted dying, or euthanasia, is illegal in the UK and can be prosecuted as manslaughter or murder, with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

Helping someone take their own life, called assisted suicide, is also a crime and is punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

Over the past 13 years, police have referred 200 cases of death or assisted suicide to the Crown Prosecution Service, and four of them have been successful.

Figures published last year by Dignitas, the charity that helps patients with a “self-determined end of life”, revealed that at the end of 2022 there were 1,528 members from Britain.

This has increased from 821 in 2012.

Some 33 people in the UK had an assisted death at Dignitas in 2022, up from 23 people the previous year.