When I was a child, I didn’t know that the way I heard the world around me was not the same as how others heard.

Because of the solutions I took to adapt, not even the school nurse detected my condition at annual hearing and vision checkups.

But when I was a prospective college student at 16 – and fell in love for the first time – my condition, generated by tumors in my auditory nerves, was inevitable: my hearing was failing, and quickly.

Medicine has come a long way in the last 30 years.

In 1993, only about 5 percent of newborns were tested for hearing loss before leaving the hospital. Now it is almost universal. Parents have to opt out of the test, and very few do.

Up to 97 percent of newborns have their hearing tested during the first days of life. The reason for this dramatic change is the knowledge of what is possible through early detection.

Many cognitive pathways that permanently affect speech and overall development form between birth and age three. Early detection leads to early treatment. That’s why there are many more children with hearing aids today than there were 30 or 40 years ago.

Matt in the hospital with his then-girlfriend Norah, after receiving his diagnosis.

Matt Hay has written about coping with hearing loss by tapping into your memories using your favorite songs, from Beck to Simon and Garfunkel.

At the other end of the age spectrum, only about 7 percent of people in their 50s who suffer from hearing loss receive treatment, including hearing aids. That number amounts to approximately 17 percent of people in their seventies who need hearing assistance.

Although more and more seniors are getting hearing aids when they need them, the numbers remain low.

Older people would be expected to accept the reality of hearing loss and take advantage of the technology available. But most of those who need help don’t get it. This is partly due to cost, partly due to vanity, partly due to an aversion to technology or a hesitancy to change.

Whatever the reason, nearly 80 percent of people in their 70s who need hearing aids don’t get them.

As big a problem as it is, there is another sector of the population for which there is almost no data available: people who experience hearing loss sometime between the first day of kindergarten and their 50th birthday.

There are many people who, for years, have been stranded on an island. Many things happen in that period of life. It would be good to know your options.

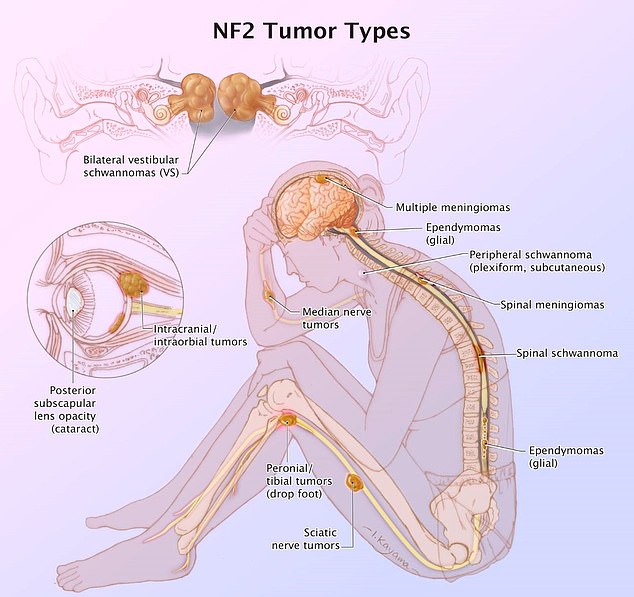

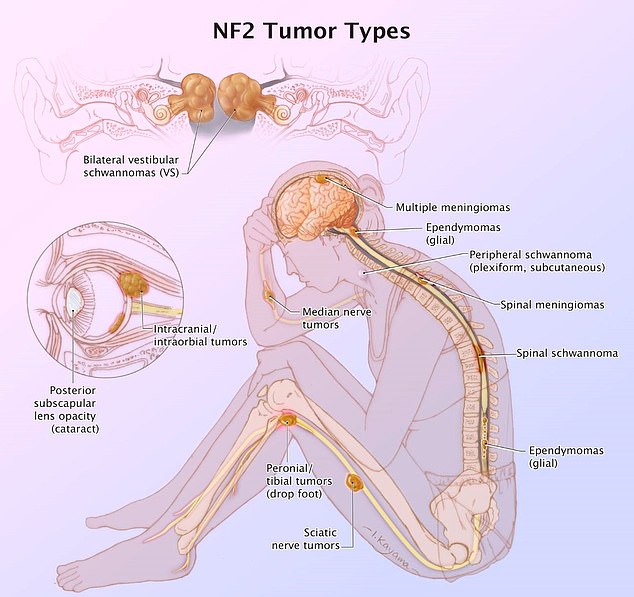

Those were some of the countless thoughts I had as I read everything I could about neurofibromatosis type 2, commonly known as NF2, the diagnosis I received from a team of specialists shortly after my initial call from IU Medical Center, when I was 19.

Today, children are universally screened for hearing loss from birth, but when Matt was born, only about 5 percent were screened.

At the other end of the age spectrum, only about 7 percent of people in their 50s who suffer from hearing loss receive treatment, including hearing aids.

For starters, I learned that my condition was genetic and relatively rare. I did not contract any viruses or develop any disorders.

Sometimes NF2 is passed from parents to children and other times it appears spontaneously. Either way, it is caused by a defect in the gene that gives rise to something called schwannomin, a structural protein located on chromosome 22.

The result of this defect is noncancerous tumors in the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves, most commonly the VIII cranial nerve, which is the auditory vestibular nerve.

That’s a complicated way of saying that there was a corrosive buildup in the wiring between my ears and my brain. It’s also a great opportunity to darkly joke that “NF tumors get on my nerves.”

The ears themselves, all the little bones and hair follicles that receive and filter sound, seemed to work fine. My eardrum vibrated as well as anyone else’s. The blockage occurred in the nerves that transmitted that sound to my brain.

Neurofibromatosis type 2 affected the nerves in Matt’s ears, causing a block in the transmission of sound to his brain.

NF2 causes noncancerous tumors in the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves.

At first I thought it was good news. Now that we had the problem isolated, the doctors could remove the tumors and I would be ready to go; like splicing a broken cable, voilà, everything is fine.

I presented that hypothesis to my doctors, who were kind enough not to laugh out loud at me. Unfortunately, as I was quickly informed, the nerves in your brain are different than the wires in your car. You can’t replace them or cut off the bad parts and tape the two ends together.

Removing my tumors was, literally, brain surgery. And the nerves in that area of the body do not respond well to scalpels. Surgeons had to remove the tumors, but no one was sure what the resulting damage would be.

Then there was the problem of the font. Even if I made it through this cutting process without any damage, I still had the genetic defect, which meant more tumors would come in the future. We could get stuck in repetition for quite some time.

As depressing as it was to realize, things got worse. The specialists informed me that, even with this surgery and others I would need in the future, I would eventually become deaf: not ‘hard of hearing’, not ‘turn the volume up a notch or two’, but deaf as a stone. . Medical experts could slow the process through treatment, but one day I would wake up and hear nothing at all.

Hearing that news was like receiving a hammer blow between the eyes. My mother’s soft humming; my father’s stories, the ones that are repeated over and over again; my fraternity brothers’ bad jokes; the guttural roar of a fast car; the ticking of a clock; the constant noise of a train: everything would disappear.

And music. Did this mean I’d never hear Paul and Artie’s tight harmonies as they raced through the grocery store at ‘Scarborough Fair’? ‘Hello, darkness, my old friend,’ indeed.

When he learned he was going deaf, Matt considered all the sounds he would miss, including the close harmonies of Simon and Garfunkel.

‘Did this mean I’d never hear Paul and Artie’s tight harmonies as they ran through the Scarborough Fair’s grocery store? “Hello, darkness, my old friend,” indeed.

Beck’s Beautiful Way was on the car stereo when Matt took his now wife Norah on their first date; It would be one of the songs most clearly cemented in his memory.

Matt and Norah: The couple is now married with three teenage children.

Sometimes anguish precedes loss. When I learned that deafness was a foregone conclusion, I panicked at first. How would you hear a smoke alarm? Can deaf people continue driving even if they cannot hear horns, trucks, or train whistles?

At the time, those worries were years away, but the brain tends to go into overdrive when processing bad news.

I also went through all the stages of grief. Some people say there are five; others say seven. I didn’t count. At first I didn’t believe the doctors. They had to be wrong. He was healthy in every other way. Based on the materials I could find on NF2, balance should have been an issue. I also read that you had cataracts in your eyes and there were lesions on your skin. I didn’t have any of that. The diagnosis had to be wrong.

The doctors agreed. They had heard all this before. Yes, sometimes there were other symptoms, some quite severe, but the most common was progressive hearing loss. My case, they assured me, was textbook NF2.

A personal soundtrack was my determined compensation for this diagnosis. As a typical Midwestern kid who grew up in the 1980s and whose life events were tied to pop music, I planned to memorize my favorite songs.

I put together a mental playlist of bands I loved and created a way to tap into my most resonant memories. And what was the clue that needed to be cemented more clearly? The one my new girlfriend and I, Nora, the love of my life, listened to in the car on our first date: Beautiful Way by Beck:

‘Reflectors on the horizon, I’m just looking for a friend Who’s going to love my baby? When she has turned the bend. The Egyptian bells ring When is your birthday. Sweet nothing, I’m talking about you. There is a hurricane approaching you.

From the book The soundtrack of silence by Matt Hay. Copyright © 2024 by Matt Hay and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.