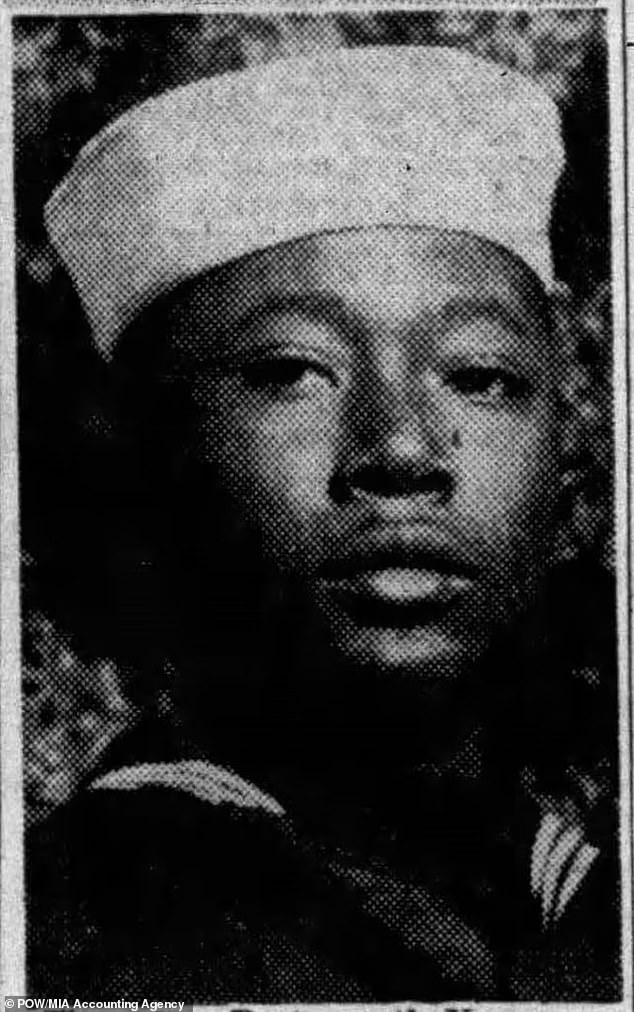

The remains of a black sailor who died during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor have finally been identified more than 80 years later.

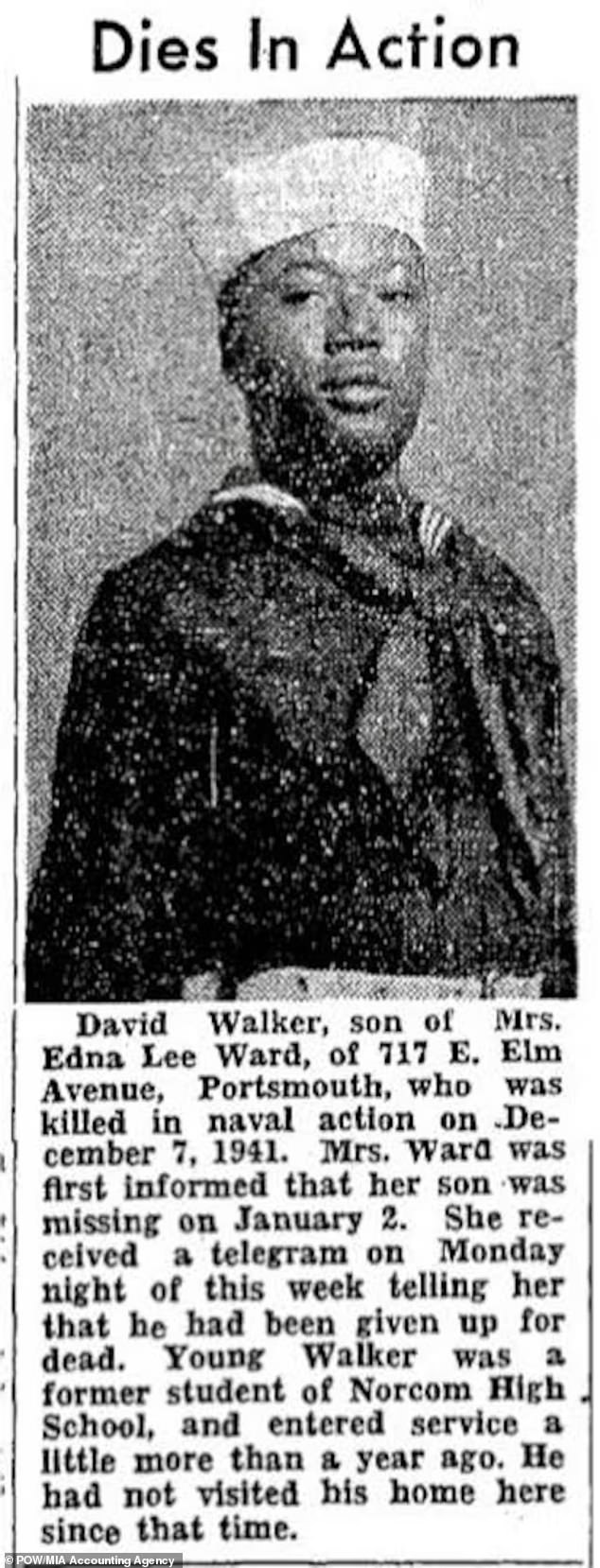

David Walker was 19 when he left his African-American high school in Norfolk, Virginia, to work as a waiter in the segregated navy.

He was on the battleship USS California, which was moored at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, when the ship was hit by two Japanese torpedoes and sank in the opening minutes of the infamous attack on December 7, 1941.

Walker was one of 103 victims who died on the USS California that day, more than 50 of whom were African-American waiters, cooks and stewards.

Last month, the Defense Prisoner of War and Missing in Action Accounting Agency (DPAA) announced that they had finally found and identified Walker’s remains.

Walker’s closest surviving relative, her cousin Cheryle Stone, who was born 30 years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, told DailyMail.com it was “heartbreaking” that her mother was not alive to witness this moment after never giving up the search. of the.

The remains of David Walker, a 19-year-old black sailor who died during Pearl Harbor, have finally been identified more than 80 years later.

He was on the battleship USS California during the attack on Pearl Harbor. The ship was hit by two Japanese torpedoes and sank.

The remains of those aboard the USS California were recovered between December 1941 and April 1942 and buried in the Halawa and Nu’uanu cemeteries.

During the first round of identification after the attack, 42 victims were named.

In September 1947, the American Graves Registration Service unearthed the remains of the victims and transferred them to the central identification laboratory at Schofield Barracks.

But lab staff could only confirm the identifications of 39 men from the USS California at the time.

The unidentified remains were later buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (NMCP), known as Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

And in 1949, a military board determined that the remains of unresolved crew members, including Walker, were not recoverable.

But then in 2018, the DPAA exhumed the remains of 25 unidentified Punchbowl sailors.

Through anthropological, dental, and mitochondrial DNA analysis, forensic scientists from the DPAA and the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System were able to identify Walker’s remains in November 2023.

Walker’s name is among the many missing soldiers etched on the Walls of the Missing at the Punchbowl in Hawaii. Now that he has been accounted for, a rosette will be placed next to his name.

Walker will be buried on September 5, 2024 at Arlington National Cemetery.

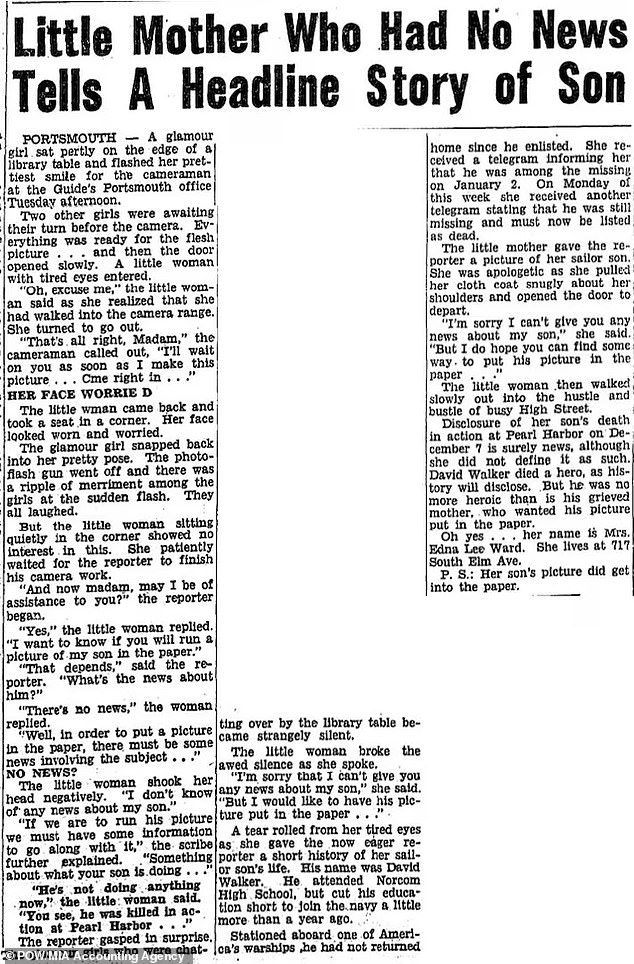

His mother, Edna Lee Ward, who died in 1951 from heart problems, had tirelessly searched for her son after the attack on the USS. She walked into a newspaper office in 1942 with a photograph of her son and asked if they could publish her photograph in the newspaper.

His mother, Edna Lee Ward, who died in 1951 from heart problems, had tirelessly searched for her son after the attack on the USS.

In 1942, he even walked into a newspaper office with a photograph of his son and asked if they would publish it in the newspaper, which they did.

His father had died of typhoid in 1923, when Walker was just one year old, according to government records.

Although Edna, who worked as a seamstress, later remarried, she had no more children.

Walker’s cousin, Cheryle Stone, of Pittsburgh, told DailyMail.com that she felt sorry for her mother.

“His mom had been looking for him all that time, it was heartbreaking,” she said.

Stone said Edna had last called and spoken to her son a few days before Pearl Harbor.

‘I feel sorry for the families. Many of their loved ones have never been identified,” she added.

‘The war is over, but people don’t think about who left next. “There are so many families who continue to suffer.”

Walker had grown up in Norfolk, Virginia, which was segregated at the time. He attended Portsmouth’s IC Norcom High School, founded as an early secondary school for black students, but abandoned his studies to join the navy.

As an African American, Walker was only allowed to work as a waiter.

Matthew F. Delmont, a history professor at Dartmouth College and author of ‘Half American,’ a study of African Americans during World War II, told the Washington Post: ‘Waiters were the lowest rank on the ship.

‘They cooked and cleaned, essentially in the service of white officers. It was an important role for the overall operation of the ship. They are the ones who ran the galleys and made sure everyone got food.

“It was the only role, at least initially at the beginning of World War II, that black men could play…in the Navy,” he added.

Delmont said finding Walker’s remains serves as an important reminder that there are still dozens of Black waiters who died and have not been identified, and many more families who still do not have answers.

Through anthropological, dental and mitochondrial DNA analysis, forensic scientists from the DPAA and the Armed Forces Forensic Medical System were able to identify Walker’s remains in November 2023.

“Their communities mourned them, just as white Americans mourned those lost at Pearl Harbor,” he told the Washington Post. “But I think it’s also a window … into the segregation and discrimination that those black Americans faced in the service of their country.”

“David Walker and most black men… in the southern states attended segregated high schools,” he added. ‘They were in segregated communities. And then they entered a segregated military, where they faced racism and discrimination virtually every day of their lives.”

The Navy remained racially segregated in training and service units until 1942, when enlisted rates were opened to all qualified persons, according to the US Navy History and Heritage Command website page.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor killed 2,403 U.S. service members, including 68 civilians, according to the Census Bureau. Nineteen US Navy ships, including eight battleships, were destroyed or damaged during the attack.