The high cost of housing is preventing Australians from having babies and is unlikely to change without radical government action, according to a new report.

While the national housing crisis is not the only factor causing Australians to postpone having children until later in life, the Population Center said it was one of the main reasons why “low fertility is here to stay.” .

Overall living costs for working families have increased by 55 percent since 2007, while average wages increased by 70 percent during the same period that national home values increased by 150 percent, according to the report.

“Rising housing costs make it increasingly difficult for young adults to achieve their goals of homeownership before starting a family,” the report states.

“This causes people to postpone motherhood until they are financially ready to buy property.”

Demographer and professor at the ANU Center for Social Research, Liz Allen, gave a blunt assessment of Australia’s falling birth rates.

“Australia is screwed… and not in a good way,” he told Daily Mail Australia on Monday night.

“Housing is out of reach, economic security is so last century, gender inequality is holding the nation back, and climate boiling is driving away the libido of young people.”

High housing costs one of the main reasons many Australians put off having children, report says

Dr Allen said falling birth rates would not be a problem if it were by choice.

“The sad reality for young people is that they are unlikely to achieve a desired family of one or perhaps two children because life is simply too hard and frankly unaffordable,” he said.

‘It is a human catastrophe that previous generations have robbed young people of a future in a broken intergenerational agreement.

‘Living standards are declining and social cohesion is eroding. “Australians are afraid.”

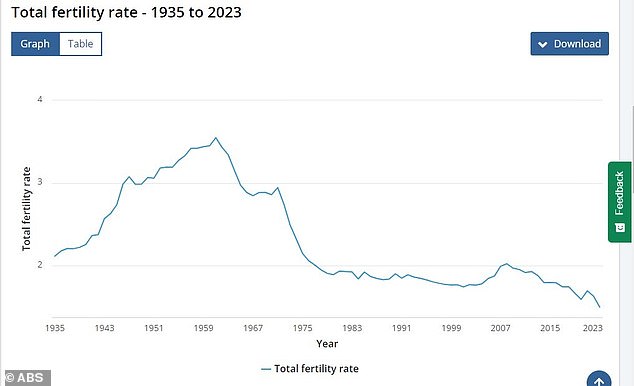

Australia saw 286,998 births recorded in 2023, representing a fertility rate of 1.5 babies per woman, up from a previous low of 1.65 in 2022, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported in October.

The Population Centre, set up by Scott Morrison’s former government to research Australia’s demographic changes, found Australians wanted to have more children but felt too financially insecure.

Demographer and professor at the ANU Center for Social Research, Liz Allen, gave a blunt assessment of Australia’s falling birth rates.

Australia’s fertility rate has been declining since peaking at 3.5 babies per mother in 1961 (pictured is a graph of the fertility rate from 1935 to 2023).

Urged all governments to consider potential new policy changes, as cited in nine newspapers.

“As we look at the gap between fertility intentions and outcomes, policies that support people to achieve the family size and composition they aspire to should be prioritized.”

Federal Treasurer and father-of-three Jim Chalmers said earlier this year that while it would be good for Australia to have higher birth rates, he ruled out reintroducing a policy like Peter Costello’s ‘baby bonus’.

‘I think people will leave it later. And sometimes, that means you’re running out of time,” Dr. Chalmers said.

‘But there are a whole host of reasons why people’s preferences are changing. It is expensive to raise children.

The number of babies last year was the lowest since 2006, when Australia’s population was at least two million fewer.

Supporting the theory that people were putting off having children, ABS data showed that the average age of an Australian mother has risen to 31.9 years, which has remained unchanged from the same peak level reached in 2022.

Dr. Allen said there will be long-term economic consequences of there being fewer children, “especially in terms of the workforce and taxpayer base.”

A report warns that “low fertility is here to stay” as birth rates in Australia fall to historically low levels.

“But for me the biggest problem is the human catastrophe of the lost but much-wanted children,” he said.

“Hope needs to be restored and action taken on procreative housing, economic, gender equality and climate policies.”

‘There is no better aphrodisiac than economic and housing security.

“No baby bonus is going to get us out of this mess – a couple of grand sucks when it comes to the costs of raising a child, and these cash incentives don’t work anyway.”