CAPURGÁNÁ, Colombia – ‘Hey! Hey you! High! Arrest!’ Three Colombian cartel soldiers yelled at me and my translator as we ducked into a small store and pretended not to hear their orders.

He had come to Capurganá, a dusty coastal town on the northwest coast of Colombia to investigate international efforts to close one of the world’s most notorious human trafficking routes: the Darien Gap.

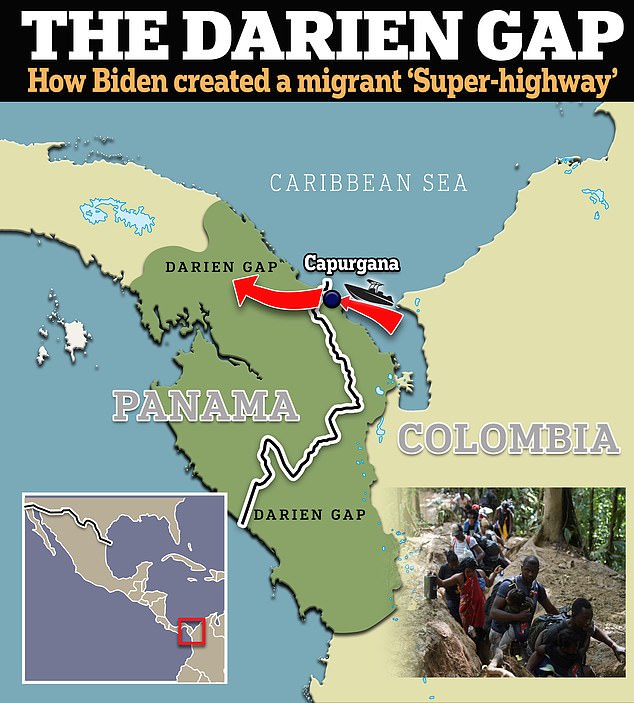

It is a 70-mile stretch of dense jungle connecting South America and Panama through which 1.5 million migrants from 170 countries have passed from 2021 to August 2024.

Capurganá is one of the last major stops before these travelers enter Central America in search of a new life further north, invariably in the US.

What I discovered surprised me and, for a poignant moment, I thought I would never understand the story.

Instead of finding some progress in curbing a historic illegal immigration crisis here, I found the opposite.

He had come to Capurganá, a dusty coastal town on the northwest coast of Colombia to investigate international efforts to close one of the world’s most notorious human trafficking routes: the Darien Gap.

Capurganá (above) is one of the last major stops before these travelers enter Central America in search of a new life further north, invariably in the US.

Hundreds of immigrants arrive daily from all over South America and from places as far away as Africa, the Middle East and China.

They are greeted at the docks by infantrymen from the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, a powerful paramilitary drug trafficking cartel that governs the region’s smuggling routes.

Immigrants pay hundreds of dollars each for passage and permission to travel north through the Darien Gap to Panama and beyond.

I had been warned that the cartel kept a close eye on everything here, so I pretended to be a tourist.

For a full day, I flew a drone out of my hotel room window, filming the gaitanistas transporting men, women, and children from the docks to the Darien Gap to begin their journey.

But when I began to document the operation from the ground, three gaitanista thugs discovered me and chased me to a convenience store.

“Hand me the camera,” one of the burly men demanded.

I backed up against the cash register.

On my phone were damning images of his activities. He felt like keeping it a secret could be a matter of life and death.

I’m just a ‘gringo’, I told them through my translator, an ‘adventure tourist’.

They didn’t believe it.

I briefly considered escape, thinking about the Taser in my front pocket. But even if we managed to escape, there was only one way out of Capurganá: the ships controlled by the Gaitanistas.

When I began to document the operation from the ground, three gaitanista thugs saw me and chased me to a convenience store. “Hand me the camera,” one of the burly men demanded. (Above) Author Todd Bensman

They are greeted at the docks (above) by infantrymen from the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, a powerful paramilitary drug trafficking cartel that governs the region’s smuggling routes.

I raised my hands in surrender. “Okay, I’ll tell you the truth about everything,” I said.

Around a cheap plastic table in a restaurant next door, I explained that I was an American journalist. Fortunately, not even the gaitanistas are so bold as to harm a Yankee.

They let me leave on condition that I take the first boat out of town the next morning, and in the meantime they ordered me to stay out of their way.

They had work to do. And they have never been busier.

For decades, fewer than 10,000 immigrants a year passed through cities like Capurganá to cross the Darién Gap.

But after President Joe Biden took office, demolished his predecessor’s security measures and essentially opened the US southern border, that number rose to 133,000 migrants in 2021.

At the time, the seven-day voyage was still famous for rapes, robberies and murders.

The indigenous inhabitants of the Panamanian side routinely murdered immigrants for their money and valuables. Women were at risk of sexual assault by other migrants and cartel guides. Flash floods along the river were known to sweep away entire families camping out in the middle of the night. The weak and injured were routinely left on the roadside to die.

Now almost everything has changed.

The current passage through the Darien Gap is no longer a tortuous seven-day trek, but a two- or three-day trek along trails heavily patrolled by Panamanian border police.

Because? In April 2022, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas signed an agreement with Panama to help alleviate the humanitarian disaster, which the Hoyuse Blanco helped create by opening the doors of the United States.

The administration declared its commitment to “safe, orderly and humane migration” around the world.

In 2023, U.S. State Department agencies further increased contributions to the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration to a staggering $1.4 billion, according to a database that tracks federal spending.

Hundreds of millions of American taxpayer dollars began flowing into Panama.

The current passage through the Darien Gap is no longer a tortuous seven-day trek, but a two- or three-day trek along trails heavily patrolled by Panamanian border police.

The nation built new immigrant processing centers and welcomed dozens of nongovernmental agencies to provide aid to illegal travelers.

The investment was so great that the once dangerous passage now resembles a “superhighway” for immigrants built by the United States. As a result, illegal immigration into the Darien Gap has skyrocketed even further.

Crossings increased to 250,000 by the end of 2022.

In 2023, 520,000 people crossed the Gap.

By the middle of this year, nearly a quarter of a million had made the trip.

The flow of migrants is so overwhelming now that the head of Panama’s National Border Service told me that his country screens less than one percent of migrants.

They used to ask up to 90 percent about their criminal records and possible links to terrorism.

No wonder Panamanians have had enough.

Panama’s new president, Raúl José Mulino, has committed to closing the crossing and, at least in writing, the Biden administration has agreed to help.

On July 1, DHS Secretary Mayorkas said the United States would help fund deportation flights of illegal immigrants from Panama back to Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela.

But that help has not yet materialized, according to President Mulino.

“I will never tire of reiterating my position before the international community,” he posted on Twitter this week. ‘The Darién will no longer be the path through which thousands of illegal immigrants continue to cross into the United States; This humanitarian crisis will come to an end.”

On Tuesday, Biden’s Treasury Department announced sanctions on a handful of leaders of Colombia’s Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces, calling the cartel “one of the largest drug trafficking organizations in the country and a key contributor to human trafficking through of the Darien Gap”.

Some may see the move as progress, but others in the region know that sanctions will not change the situation on the ground.

It is difficult for critics to see this as anything less than a weak response to a humanitarian crisis of the administration’s own making.

As long as this ‘superhighway’ for migrants built by Biden remains open, the misery and crime that feeds on it will continue.