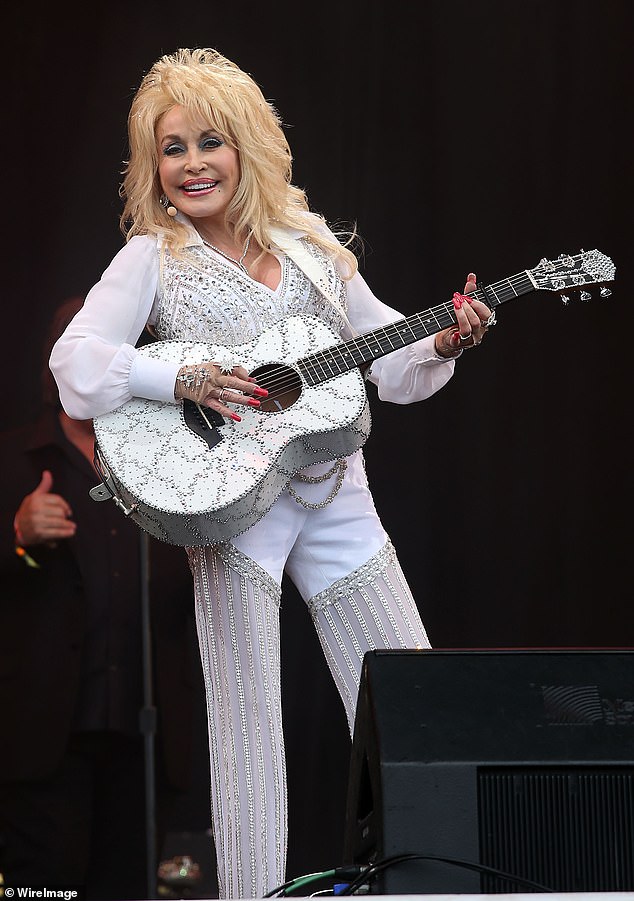

Not long ago, a post crossed my timeline with an incredibly beautiful black and white photo of Dolly Parton in the ’60s. The caption simply read: ‘What the hell was Jolene like?’ One can only wonder.

As a musical artifact, ‘Jolene’ is hard to beat.

It’s an epic piece of American music, the karaoke song of choice for many amateur fans, as well as a favorite of professional artists who want something to cover.

However, what makes it fascinating is not only its challenging melody, but its message: the narrator of ‘Jolene’ knows that she cannot compete with the song’s titular antagonist and has no intention of doing so.

Instead, she makes a plaintive appeal to the other woman’s sense of decency, and perhaps even her vanity.

“You could choose men,” Parton sings. “But he could never love again, he’s the only one for me, Jolene.” (That the man in question is not exactly a good catch is never stated outright, but rather implied; this is, remember, a guy who talks about other women in his sleep.)

Hence the excitement this month when a version of the song appeared on Beyoncé’s new album, ‘Cowboy Carter,’ and the uproar when it was discovered that Bey had changed the lyrics and, with it, the character of the song.

‘Jolene’ is an epic piece of American music, the karaoke song of choice for many amateur fans, as well as a favorite of professional artists who want something to cover.

Hence the excitement this month when a version of the song appeared on Beyoncé’s new album, ‘Cowboy Carter,’ and the uproar when it was discovered that Bey had changed the lyrics and, with it, the character of the song.

Beyoncé isn’t begging anyone not to take her man, thank you very much. What she’s telling you is that if you try, there will be trouble, maybe even violence: “I’m warning you, don’t come for my man,” she sings.

These changes are not that surprising. Beyoncé’s ‘Jolene’ begins with a spoken introduction from Parton, 78: ‘Hey, Miss Honey B, it’s Dolly P. You know that hussy with the good hair you sing about? Reminds me of someone I knew back then.

The minx in question is ‘Becky with the good hair’, an unidentified woman with whom Beyoncé’s husband, Jay-Z, had a much-discussed extramarital affair; Although the celebrity couple has always been cagey about the details of Jay-Z’s flirtation, Beyoncé periodically references it in her work.

It’s unclear whether Beyoncé’s ‘Jolene’ is intended as yet another swipe at this woman specifically, or simply a warning to anyone who has thought about following in her footsteps.

Its message, however, is unambiguous, that is, trite and predictable.

As The Atlantic’s critic wrote, “Beyoncé replaced the vulnerability that made “Jolene” one of the greatest songs of all time with a bunch of bad-bitch clichés.”

What’s interesting about these bad bitch clichés is how often they are used in the service of something that claims to be feminism, but in practice seems quite the opposite.

Threatening Jolene with violence instead of begging for mercy is, of course, the most empowering option according to the principles of YASS-KWEEN feminism, but what kind of feminism reserves all its opprobrium for the woman who pursues a married man, while he leave free? the hook?

Add to this Beyoncé’s scary, masculinized ‘if you try to touch it, I’ll kick your ass’ stance, which paradoxically reveals how disempowered and insecure she is.

If she is a queen, as the song says, and has no doubts about her man’s devotion, then why does he threaten to shake hands with any woman who gives him a sideways glance?

Threatening Jolene with violence rather than begging for mercy is, of course, the more powerful option according to the principles of YASS-KWEEN feminism. But what kind of feminism reserves all its opprobrium for the woman who pursues a married man, while she lets the man have his way?

Add to this Beyoncé’s scary, masculinized ‘if you try to touch it, I’ll kick your ass’ stance, which paradoxically reveals how disempowered and insecure she is.

But then, this kind of photogenic but ultimately insubstantial feminism is one that Beyoncé has trafficked in for a long time, dating back at least a decade, since her performance at the 2014 VMAs, where she stood in front of a screen in which ‘FEMINIST’ was projected in a giant block. letters.

At the time, all eyes were focused on the ‘FEMINIST’ sign, but when I watch the video of that performance now, what stands out to me most is the faceless silhouette of her body against it: high heels, legs akimbo , practically indistinguishable from the stock images that appear on brochures for a certain type of establishment in Las Vegas or Atlantic City.

Of course, when those places use these types of images, it is objectification and sexism. But with Beyoncé it’s different, you know, for some reason.

It’s not that you can’t be sexy and be a feminist at the same time, but there’s always been something a little strange about the idea circa 2014 that feminism itself is sexy, that this is its main appeal.

This same mentality has given us a culture in which various archetypes of female resilience have increasingly been replaced by the “badass,” a woman who has no feelings or flaws, and who has little use to other people except as a casual sexual partner. or punching bags.

It is ironic, in a world where women can follow increasingly varied paths to fulfillment, that the representation of feminine strength in art has become increasingly narrow, one-dimensional and masculinized.

The princess who rescues herself; the emotionally distant action heroine; the invulnerable, workaholic, commitment-phobic playgirl; a lot of ‘strong female characters’ these days are basically men, but with boobs.

This category arguably includes the unnamed protagonist of Beyoncé’s ‘Jolene’, making the song an interesting example of the phenomenon whereby a supposedly feminist update ends up being less enlightened than the original work of art.

Parton’s song is actually sneakily subversive, even when it doesn’t pass the Bechdel test: These women are talking about a man, yes, but he’s more of an accessory than a person.

Note that the singer doesn’t beg you not to leave; he is not consulted, or even present, because he is not in charge. Instead, his fate is in the hands of two women: the one who loves him despite herself and the one who could have him, but hopefully she won’t.

The narrator of the original ‘Jolene’ is definitely not bad, but that’s the point, and it’s something she’s not ashamed to admit.

She is heartbroken at the thought of losing her man. But she’s not stupid either; she knows that her best chance at happiness requires taking advantage of Jolene’s decency, woman to woman, or, possibly, preempting any man-stealing impulses Jolene might have had by respectfully cajoling her into submission.

Here I admit that after listening to the song on repeat for most of the day, Parton’s lyrics began to remind me of the scene from ‘The Hobbit’ where Bilbo Baggins tries to disarm the dragon Smaug by giving him an increasingly flowery dress. series of superlatives: Smaug the Magnificent. Smaug, the greatest and greatest of calamities. Smaug to the incredibly rich! And as such, Smaug surely has much better and more important things to do than eat an unimportant hobbit.

The song is an interesting example of the phenomenon whereby a supposedly feminist update ends up being less enlightened than the original artwork.

Perhaps Jolene’s narrator is truly the smiling, pathetic creature she pretends to be.

Or maybe you’ve simply discovered that the best way to get what you want from a more powerful person is to make them feel magnanimous by giving it to you.

And while the new ‘Jolene’ struts around with her chest out, making superficially feminist noises (and, as such, acts as catnip for Beyoncé fans), it’s Parton’s who imagines women more fully, the that recognizes female power as it exists beyond the superficial archetype of the badass bitch.

There is the soft power of the seductress, whose charms no one can resist. And there is the even softer power of the supplicant who, as another song would say, is not too proud to supplicate.

This article was originally posted by UnHerd.