EXCLUSIVE

Emails reveal Brittany Higgins’ ex-boss threatened to sue Network Ten and Lisa Wilkinson for a staggering six-figure sum over an extract from a Project interview that was played on the Logies.

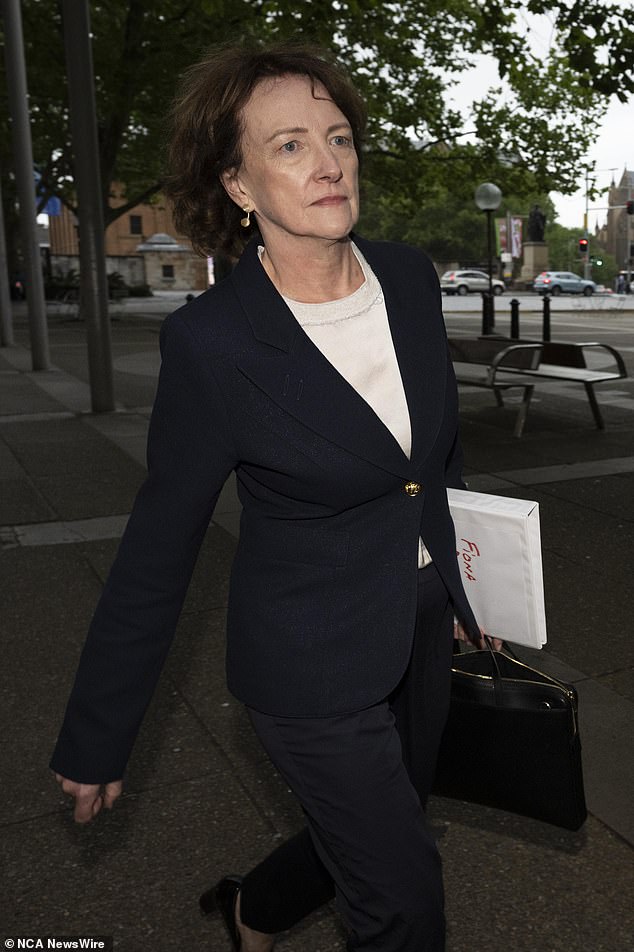

Daily Mail Australia has obtained a series of emails sent to Channel 10’s lawyers that show Fiona Brown, Ms Higgins and Bruce Lehrmann’s former boss in Parliament, threatening to sue the network and Wilkinson.

Brown objected to a Logies segment showing Wilkinson’s award-winning story The Project, originally broadcast in February 2021, which reveals Higgins’ allegations that she was allegedly raped by Lehrmann two years earlier.

Mr. Lehrmann has always denied the allegations.

Her lawyer sent a legal letter, stating that Ms Brown could expect to get $443,000 in damages from Network Ten if the case went to trial, but that she would accept a payout of $150,000.

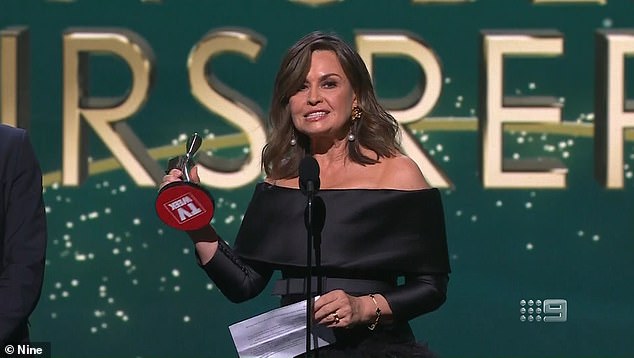

It was Wilkinson’s second legal headache since the June 2022 awards night; the first was that her Silver Logies victory speech over his interview with Higgins delayed Lehrmann’s criminal trial.

An email from Wilkinson to Ten’s lead litigator Tasha Smithies shows The Project host slamming Ms Brown’s complaint as “absolutely ridiculous”.

Fiona Brown appears in court in December during Bruce Lehrmann’s defamation trial against Network Ten and Lisa Wilkinson.

Lisa Wilkinson is pictured during her 2022 Logies acceptance speech

“Thank you for letting me know, Tasha,” he wrote on January 17, 2023. “The entire premise of your complaint is completely ridiculous… and the Logies thing is palpably false.”

Ms Brown complained that neither Wilkinson nor Ten asked the Logies not to broadcast the segment, a claim which was dismissed by Ten’s lawyers.

In her response to Wilkinson, Mrs Smithies wrote: “We hope this is the last time we hear from Fiona Brown.”

Brown was chief of staff to former defense industry minister Linda Reynolds in 2019 when Higgins alleges she was raped.

During her interview with The Project, Higgins claimed that Brown did not support her when she first revealed her alleged rape and made her choose between filing a complaint with the police or keeping her job.

Brown has long maintained that those claims were false and that he only tried to support Higgins after she first revealed the alleged rape to him, even offering to take her to the Australian Federal Police to make a formal complaint.

At the Logies, which were broadcast on Channel Nine, rather than Ten, a clip of the program was played before the winner was announced.

Lisa Wilkinson is pictured interviewing Brittany Higgins for the February 2021 episode of The Project.

Brittany Higgins is pictured with her fiancé David Sharaz in France, where they now live.

That clip included several statements Ms. Higgins made against Ms. Brown, which were not made clear in the correspondence obtained.

A week after the Logies, Ms Brown’s lawyer, Walter MacCallum, sent a notice of concern (the first step in the defamation process) to Thomson Geer, the law firm used by Network Ten.

In another letter dated 22 December 2022, MacCallum said Brown would settle for $150,000 in damages and an apology to be broadcast on The Project, and signed apologies from Wilkinson and Network Ten respectively.

“Network Ten and Ms. Wilkinson will together pay our client the full sum of $150,000 in lieu of damages,” the letter said.

“Network Ten and Ms Wilkinson will pay our client’s legal costs incurred before this offer was made and our client’s legal costs of any further negotiation or agreement of the terms of any required documentation, on an attorney/attorney basis. customer”.

In response, the network attempted to argue that Ms. Brown had left it too late to bring defamation proceedings because there is a one-year time limit, and the notice of concern was sent 16 months after The interview. Project would air.

The limitation period can be extended if the claimant (Mrs Brown, in this case) successfully argues that it was unreasonable to start the proceedings earlier, something Mr MacCallum said he would be willing to do.

Bruce Lehrmann is pictured outside the Federal Court in Sydney last week.

Ten also argued that he was not involved in the broadcast of that particular clip at the awards ceremony on Channel Nine.

However, MacCallum noted that the notice of concern after Logies was the second the network received regarding the way Ms. Brown was portrayed in the Project’s original interview in February 2021.

He said the network was aware of Ms Brown’s concerns regarding the original broadcast of The Project and asked why they did not anticipate that parts of the interview could be rebroadcast on the Logies.

MacCallum also questioned why the network did not ask for the clip to be removed from Nine’s website after the interview was broadcast, and pointed to the acceptance speech Wilkinson gave after the clip was shown.

During the acceptance speech, Wilkinson appeared to side with Higgins and refer to her as a proven rape victim rather than an alleged rape victim.

At the time, Mr. Lehrmann’s criminal trial was just days away.

Network Ten’s senior litigator Tasha Smithies is pictured outside the Federal Court last week.

The ACT Chief Justice moved the hearing as a direct result of the speech over fears it may have biased the jury against Mr Lehrmann, destroying his chance for a fair trial.

In his letter to Thomson Geer, MacCallum wrote: “Neither Ms Wilkinson’s speech, nor the interview footage nor the Logies presentation is, or was, an expression of opinion based on true or untrue facts.”

He said the combination of the interview extract and Wilkinson’s speech were problematic because, together, they implied that Ms Higgins’ allegations against Mr Lehrmann and her claims against Ms Brown were correct.

Ten rejected Ms Brown’s claim.

“Our clients maintain that any defamation action by their client would be futile and doomed to failure,” said attorney Marlia Saunders.

“While our clients wish their client no ill will, they will vigorously defend any proceedings brought against them.”

It was unclear what happened next, if anything.