BBC Radio presenter Garry Richardson has left Radio 4’s Today program after 43 years with his last show on September 9, exactly 50 years after he joined the corporation.

The news reporter, 68, whose voice is known to millions of people as he reads headlines from around the sports world, shared an emotional statement after his departure was confirmed.

Saying: “I’ve had a great time working for the BBC alongside my sporting and showbiz heroes.”

“I’ll still stream from time to time, the only difference will be I won’t set my alarm for 2.45am and that’s a lovely idea.”

BBC Radio presenter Garry Richardson, 68, has left Radio 4’s Today program after 43 years with his last show on September 9, exactly 50 years since he joined the corporation.

The journalist, whose voice is known to millions of people because he reads headlines from around the sports world, shared an emotional statement after his departure was confirmed.

Garry joined the BBC in 1974 as a researcher before moving into radio and then joining the Today program in 1981.

He previously presented BBC Radio 5 Live’s Sportsweek for 20 years until his final episode in 2019.

Today editor Owenna Griffiths said: “Garry quickly became a familiar part of my morning when I started listening to Today at university.”

“It has been a privilege to work with him over the years and, along with many, many other Today listeners, I will miss him enormously.”

While BBC director general Tim Davie praised “legendary presenter” Garry, saying in a statement: “Many of us have woken up to him bringing the latest sports news for more than four decades. He has brought wisdom, insight and a smile with every transmission’.

Before adding: ‘On behalf of us all, I would like to thank Garry for everything he has done, fifty years at the BBC is an incredible milestone.’

It comes after Radio 2 fans criticized the BBC for giving Paddy McGuinness a new regular Sunday show while criticizing the broadcaster’s “obsession” with filling radio slots with celebrities.

Paddy, 50, will front a new Sunday show on Radio 2, replacing Michael Ball’s original Sunday slot of 11am to 1pm.

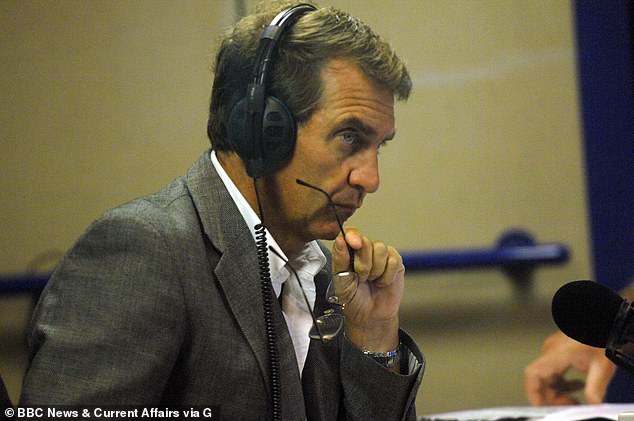

Saying: ‘I’ve had a wonderful time working for the BBC alongside my sporting and showbiz heroes’ (Garry pictured interviewing Serena Williams)

Garry joined the BBC in 1974 as a researcher before moving to radio and then the Today program in 1981.

Meanwhile, it is now confirmed that Michael presents Love Songs With Michael Ball from 9am to 11am from June, taking over Love Songs from Steve Wright following the veteran DJ’s sudden death earlier this year..

Following the announcement, Radio 2 fans took to X, formerly known as Twitter, to criticize the decision and ask the BBC to consider hiring talented local DJs.

They wrote: ‘Seriously @BBCRadio2, can’t you find new talent on local radio instead of horrible “celebrities”? No wonder people are turning away.

‘Do you agree with what happened to choosing and giving a chance to talented local DJs instead of giving away radio shows to celebrities? “They seem obsessed with doing this.”

‘Is there REALLY no one else???? I would be very discouraged from trying to start a career in radio when you see decisions like this.’

‘Why do they give airtime to celebrities, poor ones at that, instead of encouraging new talent? I’m glad Michael Ball, Bob Harris and Tony Blackburn are still around!’

Paddy’s new show comes after it was revealed that comedian Romesh Ranganathan will take over Claudia Winkleman’s Saturday show on Radio 2 from next week.

It comes after Radio 2 fans criticized the BBC for giving Paddy McGuinness a new regular Sunday show while criticizing the broadcaster’s ‘obsession’ with filling radio slots with celebrities.