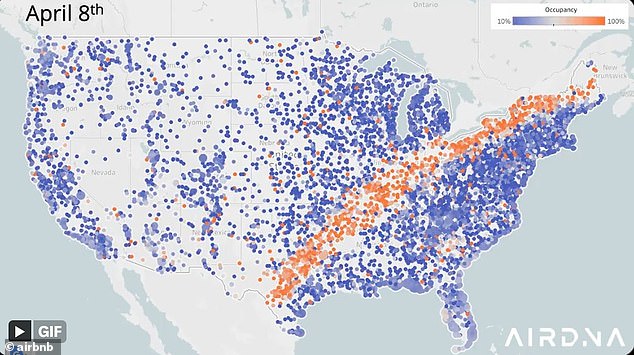

A map of Airbnb bookings in the United States has revealed how much solar eclipse hysteria has spread across the country.

The image shows Airbnb occupancy rates nationwide for April 8, when the moon completely blocks the face of the sun in one of the largest astronomical events of the decade.

The blue dots represent low occupancy, around 10%, and the orange dots represent maximum occupancy: 100%.

The map shows a large orange swath stretching from Maine to Texas, following the solar eclipse’s 100-mile-wide path of totality.

More than 20 million people in the United States traveled elsewhere to watch the previous eclipse, which occurred in 2017.

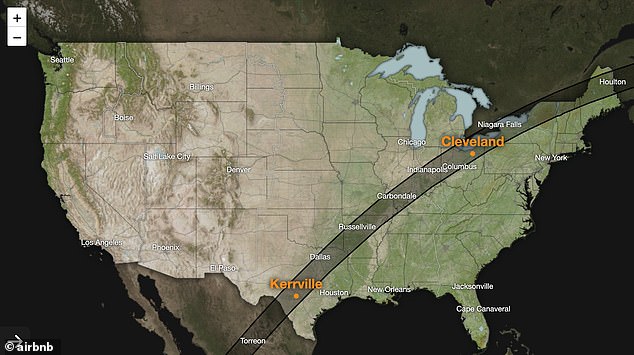

Experts estimate that millions more Americans will travel for this next solar eclipse, which will occur on Monday, and will begin in its entirety in Dallas, Texas, around 1:40 pm and last until 1:44 pm CDT.

A new Airbnb booking map reveals how desperate people are to find suitable accommodation to view the eclipse: orange dots showing 100% occupancy rates and blue dots showing only 10% occupancy rates.

High reserves follow the path of totality of the April 8 solar eclipse

This widespread surge in interest in the eclipse has benefited Airbnb, which appears poised to cash in on the solar craze.

The app, which offers short and long term accommodation, reported At the end of February they had recorded a ‘1,000% increase in searches for stays along the path of the solar eclipse of totality in the United States.’

They further noted that “Airbnb listings outnumber hotels by more than 15 times along the path of totality in North America, offering more amenities and in more communities along the path of totality.”

To accommodate the rush of skywatchers, more than 1,000 new Airbnb hosts “plan to welcome first-time guests to help meet demand.”

Within the path of totality, the cities that will receive the most visitors are Austin and Indianapolis followed by Cleveland, Dallas and Montreal.

Most travelers will come from New York City or Mexico City.

The eclipse, which briefly darkens the outside during the day, will be visible to about 32 million people across a narrow strip of North and Central America.

It will mark the first total solar eclipse visible anywhere in the world since December 2021, and the first seen from the US since August 2017.

Dr Greg Brown, astronomer at Royal Greenwich Observatory, said: “For North American observers, this is the best chance of seeing a total solar eclipse this decade.

“Nothing compares to the day turned into night that arises from a total eclipse.”

This motorhome/caravan in Pelham, Canada usually costs $129 a night and is reserved for Monday’s eclipse. Many tourists flock to places like this, where their views will be free of light pollution.

On April 8, the total solar eclipse will be visible along a ‘path of totality’, starting in Mexico and passing through Texas, where it will travel to New England and end in Canada.

Anywhere along the path of totality, people will see a partial eclipse followed by the total eclipse, and then a partial eclipse again.

Whatever your location along the path of totality, the total eclipse should be visible for about four minutes.

According to Dr. Brown, a total solar eclipse occurs when the moon and sun align “perfectly.”

He told MailOnline: “Only when it aligns perfectly, so that the center of the Sun and the center of the Moon pass in front of each other, is that a total solar eclipse occurs.”

The place where the total solar eclipse is visible is known as the point of totality, but this is just the very center of the moon’s ever-moving shadow.

Elsewhere in the Moon’s shadow, further from the center, a partial solar eclipse will be seen on April 8.

“The partial solar eclipse occurs because, from our point of view, the center of the Moon is slightly above or slightly below the center of the Sun,” Dr. Brown said.

On April 8, because the Moon will be at the closest point to Earth in its orbit (known as ‘perigee’), it will appear larger, big enough to cover the entire Moon.

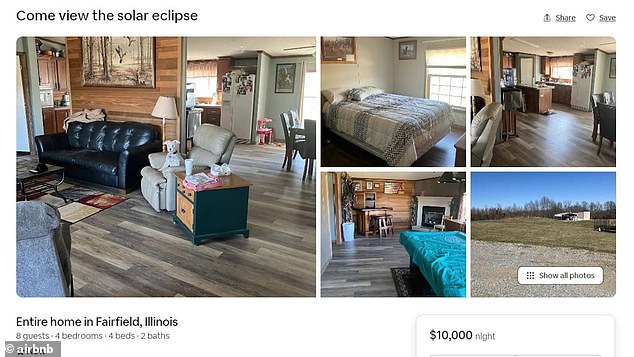

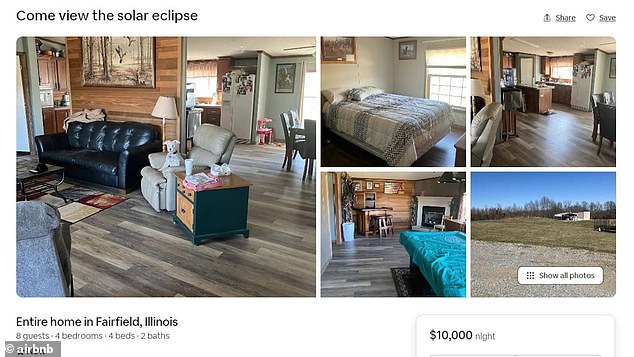

Some users spend huge sums of money on proper accommodation. This accommodation in Fairfield, Illinois, which has already been booked for the eclipse, will cost $11,412 for a single night when all rates are added up.

Airbnb said new data revealed that during the last eclipse, 10% of guests decided to book with Airbnb for the first time, inspired to try the app so they could observe the solar phenomenon.

Some of the listings come equipped with “telescopes and observatories designed to elevate any solar eclipse experience to stellar heights.”

In Fairfield, Illinois, an entire house is sold for the price of $10,000 per night, which, combined with other rates, actually totals $11,412 per night.

The property, four miles north of a dead-end road, features 25 open acres, four bedrooms and two bathrooms.

Other tourists are splurging on luxurious glamping sites, like this one in Clarksville, Arkansas, which says on its profile that ‘the entire place will be dedicated to the solar eclipse!’ Like many other places, the Clarksville Airbnb is already booked.

But now, new weather patterns and extensive cloud cover threaten to ruin the viewing experience for many travelers.

Parts of Texas, including Dallas, face an increased risk of view-obscuring thunderstorms.

And in addition to bad weather, there will also be an increase in traffic to contend with.

During the 2017 solar eclipse, there was a significant increase in traffic risks, according to cnn.

Some places are taking drastic measures to ensure the safety of their residents as their cities prepare to be overwhelmed by tourists.

In the Canadian region of Niagara, which is at the top of the eclipse path, officials declared a state of emergency to try to prepare for an influx of millions of tourists.

Niagara Falls is in the path of totality and will likely experience 100 percent coverage for about 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

Niagara Falls Mayor Jim Diodati estimates that around a million tourists will flock to see the spectacle – 14 times more visitors in a single day than the city normally sees in a year.

The state of emergency “strengthens the tools the region has at its disposal to safeguard the health and safety of residents and visitors and protect our critical infrastructure in any scenario that may arise,” according to the official announcement.

This listing in Tupper Lake, New York, has already been reserved for Monday’s eclipse for the price of $1,093. In 2017, 10% of Airbnb guests were new users and were encouraged to try the app to see the eclipse.

This glamping site in Clarksville, Arkansas, has already been booked for Monday’s eclipse. Located near Horsehead Lake, the site will cost visitors $330 per night. For this upcoming eclipse, more than 1,000 new hosts will join the app to offer their properties to the influx of visitors.

Some Airbnb accommodations, like this one booked in Austin, Texas, offer users telescopes, observatories, and other amenities to enhance their eclipse viewing experience.

But tourists seem undeterred. The next solar eclipse of this magnitude won’t occur again until 2079, making Monday’s event a once-in-a-lifetime experience for many.

Depending on where you are in the path of totality, the eclipse could last up to four minutes.

It is vitally important to view the eclipse through a pair of ISO 12312-2 certified glasses, as our eyes are extremely sensitive to light and can be seriously injured when exposed to direct sunlight.

As the sky darkens during a solar eclipse, observers along the path of totality will see the sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere, which appears as a ring of bright light and can cause eye damage.