When George Washington was a child, the story goes that he cut down a family cherry tree and then confessed with the immortal words: “Father, I cannot lie…”

If only all politicians were this honest. The story is probably apocryphal and created by one of Washington’s early biographers, Mason Locke Weems. But Washington, for which the nation’s capital is named, was responsible for many real achievements.

This becomes clear when visiting Mount Vernon in Virginia, the home of America’s first president, overlooking the Potomac River, 16 miles south of the White House.

Before overseeing the drafting of the Constitution and defeating the English (with the help of the French) and consolidating American independence at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, Washington had moved into his family home in 1754.

His father had built the grand mansion in colonial Virginia on 8,000 acres about 20 years earlier.

George inherited the estate, which produced whiskey, raised cattle, and grew tobacco on the plantation (largely worked by slaves) after the deaths of his father and older brother.

The slave quarters are to the left of the lawn that leads to the imposing façade of the house. Inside there are rough-hewn wooden bunk beds and brick floors. In the last year of Washington’s life, in 1799, more than 300 enslaved African Americans lived on the Mount Vernon plantation.

The main house has a terrace with panoramic views of Maryland’s thick forests across the Potomac Whirlpool.

Tom Chesshyre visits Mount Vernon, pictured, the home of the first US president, George Washington.

A four poster bed inside Mount Vernon. The interior also features framed landscapes and portraits, a piano, and decorative stucco ceilings.

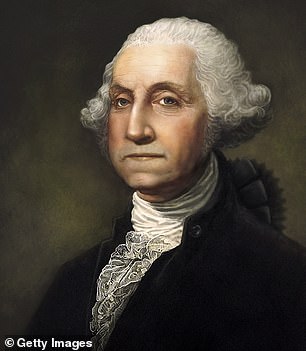

Washington (above) moved into the family home in 1754.

This forest has been purchased by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, which oversees the property (now 500 acres), so visitors will always be able to enjoy the view as Washington, his wife Martha, and their children would have done. Their son and daughter were from Marta’s previous marriage (they did not have their own).

The house appears to be made of stone, although it is made of wood and covered with a masonry-like sand mixture.

Inside there is a prominent staircase and a hall with rooms decorated in bright greens and blues, with framed landscapes and portraits, a piano and decorative stucco ceilings.

Significantly, the room displays a box with a key to the Bastille in Paris, a symbol of the French Revolution in 1789 given to Washington by the Marquis de Lafayette, a French military officer who joined the Continental Army and aided in victory in Yorktown.

Washington died at age 67 from a throat complication; He rests in a tomb to the right of the house, near a slave cemetery.

“The slave quarters (above) are to the left of the lawn leading to the imposing façade of the house,” says Tom.

In his study is the desk where he wrote his will, in which he freed his slaves upon Marta’s death.

Washington had been influenced by abolitionists, one guide says, adding that his decision to serve only two four-year terms sets an “important precedent.”

Washington did not want to be a “king.” It is unclear what he would make of the ongoing fight for the White House; Suffice it to say that the United States he led in the 18th century are far removed from those of today.