A group of American soldiers fighting in Israel Defense Forces (IDF) units in Gaza are under review after creating a social media profile dedicated to sharing images of blindfolded Palestinian prisoners and calling on people to “join the hunt” for Hamas.

The ‘Hamas Hunting Club’ has released a series of images since its creation in November showing dozens of Palestinian detainees blindfolded, sitting on the ground and with their arms tied.

Other images with a location tag from Gaza City appear to show club members posing for the camera and brandishing assault rifles while disheveled and handcuffed Palestinians remain unable to see through the rags covering their faces.

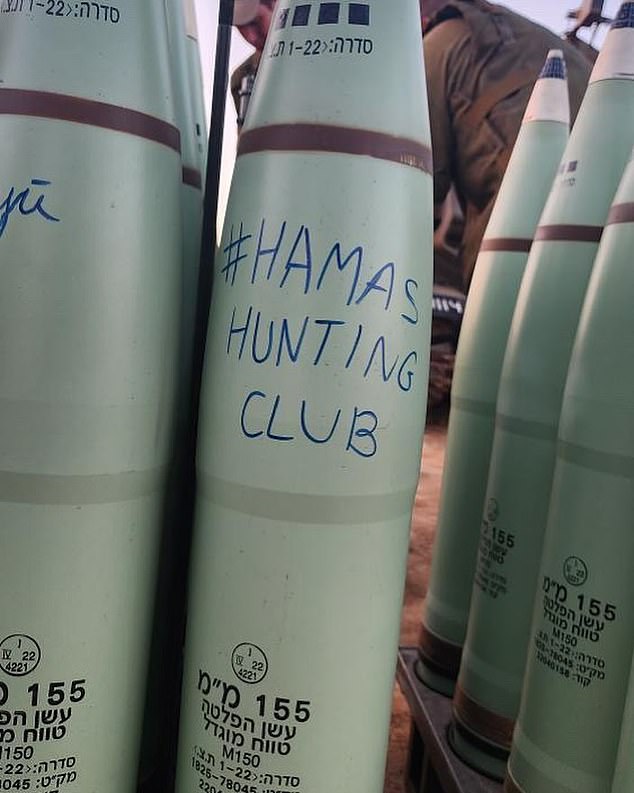

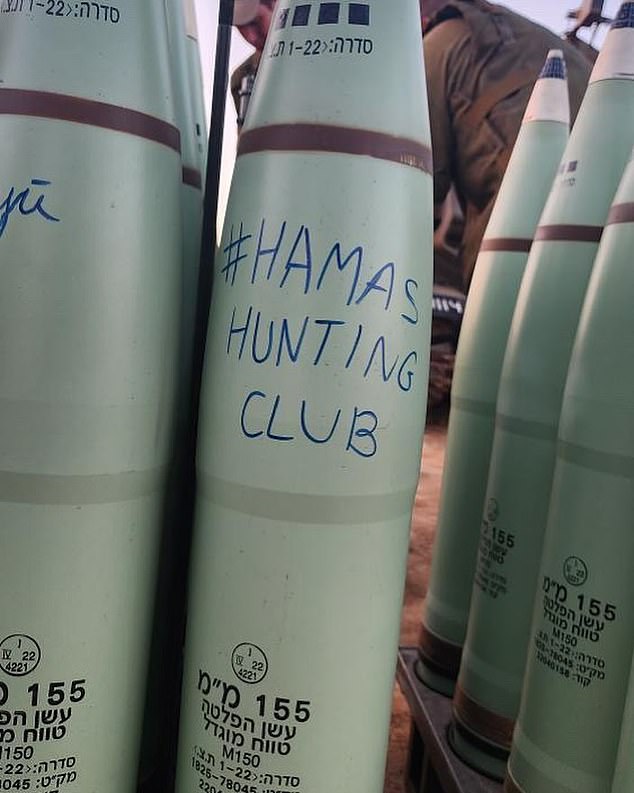

Another photo showed a smiling man holding an artillery shell destined for Gaza that had the words “send nudes” emblazoned on it.

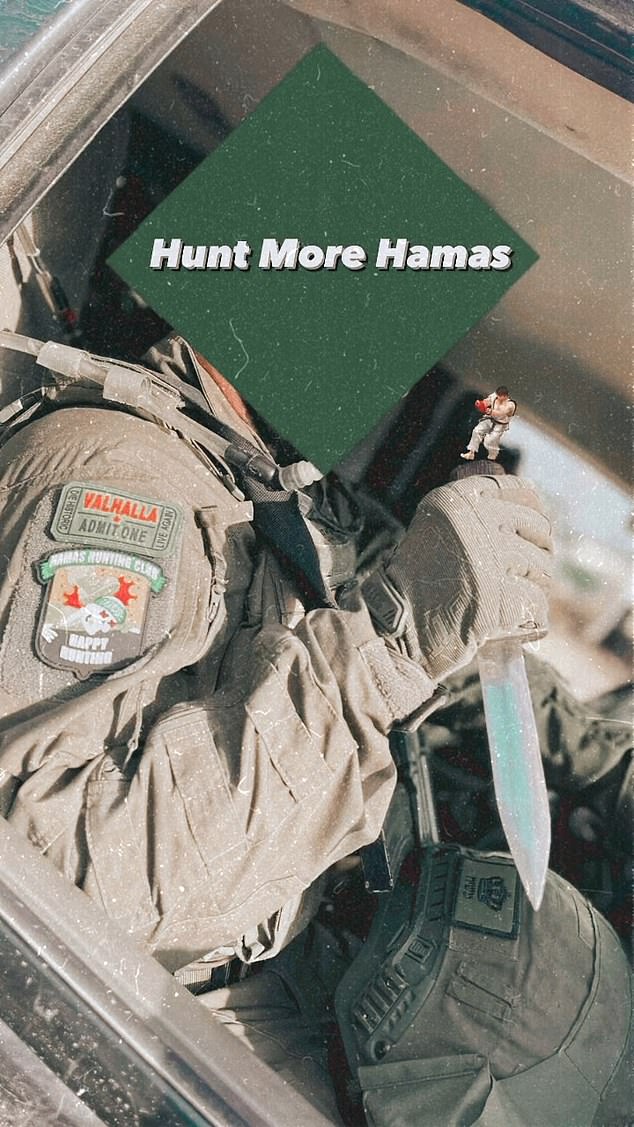

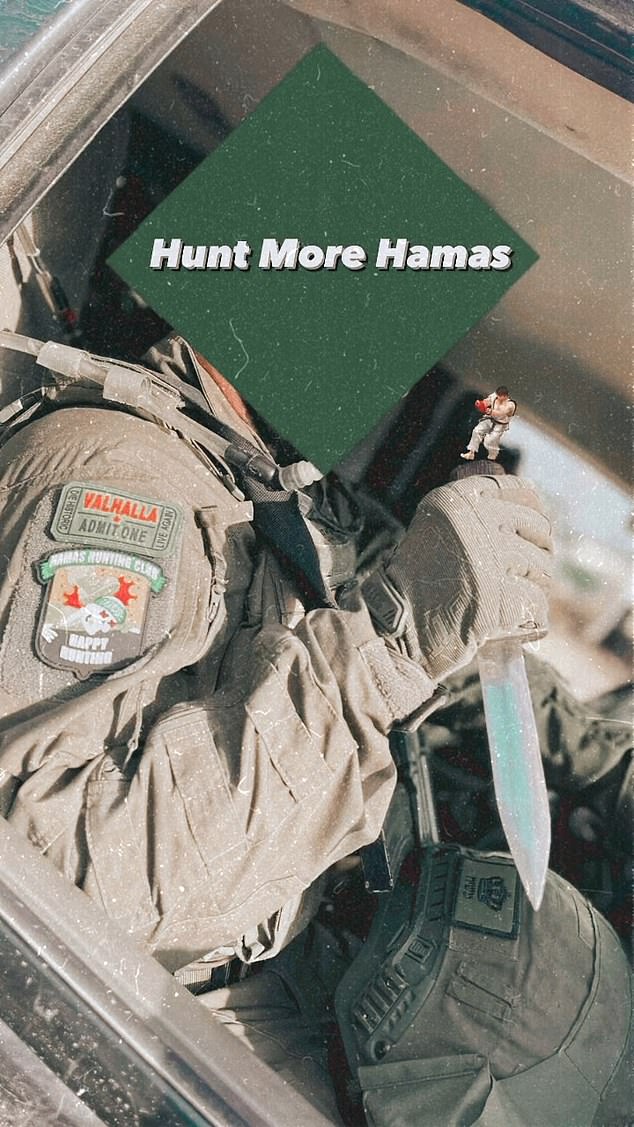

In almost every image, soldiers are seen wearing or holding the club’s distinctive patch: an image of a Hamas fighter’s skull crushed under an IDF boot.

And some posts even included clips of soldiers heading into battle overlaid with popular tracks by American rappers Eminem, Wiz Khalifa and Megan Thee Stallion.

Imploring social media users to “join the club,” page administrators are now distributing Hamas Hunting Club patches and other products to a growing number of followers.

The ‘Hamas Hunting Club’ has released a series of images since its creation in November that showed dozens of Palestinian detainees blindfolded, sitting on the ground and with their arms tied.

The soldiers are seen posing for the camera next to the captives and holding the Hamas Hunting Club patch.

Artillery munitions were seen emblazoned with the words “send naked.”

In almost every image, soldiers are seen wearing or holding the club’s distinctive patch: an image of a Hamas fighter’s skull crushed under an IDF boot.

Imploring social media users to “join the club,” page administrators are now distributing Hamas Hunting Club patches and other products to a growing number of followers.

The IDF has previously investigated several of its soldiers after images of them humiliating Palestinian detainees were shared on social media, and has sought to discourage such behavior as international pressure mounts on Tel-Aviv to agree to a ceasefire. the fire.

In one incident, an IDF reservist was discharged after being filmed abusing seven Palestinian workers near Hebron in the West Bank after they were caught trying to enter Israel without a permit.

The images showed Palestinian men naked or semi-naked, blindfolded and handcuffed, and screaming in pain. One of them is being dragged along the ground.

A screenshot of the video shows a soldier stepping on the head of one of the Palestinians with his boot, while another points a gun at him.

In another scene of violence caught on camera, a soldier kicks a blindfolded Palestinian in the stomach, then spits on him and insults him in Arabic.

They then leave him to languish in pain on the concrete while covering him with an Israeli flag.

In a statement responding to the clips late last year, the IDF said: ‘The (soldiers’) conduct that emerges from these scenes is serious and inconsistent with the IDF’s values.

‘The incidents are under investigation. IDF commanders will hold talks with all soldiers on the front. A soldier has been dismissed from reserve duty.’

However, critics of the IDF have claimed that there is little chance that its soldiers will face punishment for such treatment of detainees, which they say contradicts the Geneva Conventions which dictate that detainees must be treated humanely and protected from “insults and public curiosity.”

Many of the soldiers seen in the images shared by the Hamas Hunting Group profile have their faces blurred, but some were willing to share their identities openly.

MailOnline has contacted the IDF for comment on the Hamas Hunting Group and the status of its investigations into the account.

Some soldiers had their faces blurred, but others openly revealed their identity on social media.

In this social media post, a member of the Hamas Hunting Club is seen holding a knife.

Artillery shells are seen with the words “Hamas Hunting Club.”

Club administrators are encouraging more social media users to join the movement.

The Hamas Hunting Club sells products on social networks to thousands of followers

The IDF has previously investigated several of its soldiers after images of them humiliating Palestinian detainees were shared on social media.

There have been several cases in which Israeli troops humiliated and posed with Palestinian captives.

The war between Israel and Hamas is now entering its sixth month, and the intensity of the fighting has left much of the Gaza Strip in ruins and many people, especially in the devastated northern region, struggling for food to survive.

The United States, Qatar and Egypt have spent weeks trying to negotiate a new armistice deal in which Hamas would free up to 40 hostages in exchange for a six-week ceasefire, the release of some Palestinian prisoners and a major influx of aid to the territory. isolated.

But talks have so far made no progress despite international pressure to end the fighting.

Aid groups have said it has become nearly impossible to deliver supplies in most of Gaza due to difficulty coordinating with the Israeli military, ongoing hostilities and a breakdown in law and order.

Israel launched its offensive after Hamas-led militants stormed the border on October 7, killing about 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and kidnapping about 250.

More than 100 hostages were freed in November in exchange for 240 Palestinians imprisoned by Israel, but the sides have failed to agree on a cessation of hostilities since then.

Meanwhile, the total Palestinian death toll exceeds 30,700, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, which also It says more than 72,000 people have been injured.

British Foreign Secretary David Cameron said this week he will warn a member of Israel’s War Cabinet that allies’ patience is wearing thin over the dire humanitarian situation in Gaza.

Cameron will meet today with former Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz, who will stop in London on his return from a trip to Washington.

Cameron told members of Parliament’s House of Lords on Tuesday that people in Gaza “are starving” and that Israel must allow in more humanitarian aid.

“We have asked the Israelis for a number of things, but I must inform the House that the amount of aid they received in February was about half of what they received in January,” he said.

“Patience therefore needs to be exhausted and a whole series of warnings need to be given, starting, I hope, with a meeting I will have with Minister Gantz when he visits the UK.”

Gantz, a rival of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, is visiting Washington and London without the approval of the Israeli prime minister.