The competition is strong, but in my opinion the most important geopolitical statement so far this year came on Monday from an obscure Israeli news site.

A member of Saudi Arabia’s royal family had reportedly told broadcaster Kan that in his opinion Iran had started the Gaza war by ordering its proxy group Hamas to massacre Israelis on October 7.

Tehran’s intention, according to this unnamed royal, was to thwart the imminent normalization of diplomatic relations between Israel and the Saudis.

Why is that so important? Because it symbolizes the extraordinary transformation taking place in Middle East politics. For a Saudi royal to express such a view – that a Muslim country instigated the conflict in order to sow discord – would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. But that’s not the only way the winds of change are resetting alliances in this volatile region.

Iranians gather in Tehran to demonstrate in support of their government’s attack on Israel

On Saturday night, Iran’s ayatollahs inflicted their first direct attack on Israel since coming to power with the 1979 revolution.

For 45 years, the Islamic Republic has plotted the destruction of what its Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei calls “the evil Zionist regime.” But it has left the actual attacks to its proxies, such as Hamas and Hezbollah.

This new attack caused almost no damage, thanks to the defensive coalition that shot down almost all the weapons directed against Israel.

Allies such as the United States and the United Kingdom played a role in this. But they were joined by two other countries for whom defending the Jewish state would have been a fantasy until recently: Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

For most of the time Israel has existed, Saudi Arabia, as one of the world’s leading Muslim nations and home to the holy city of Mecca, has been its implacable enemy. But now it is on the verge of not only tolerating Israel but becoming an ally.

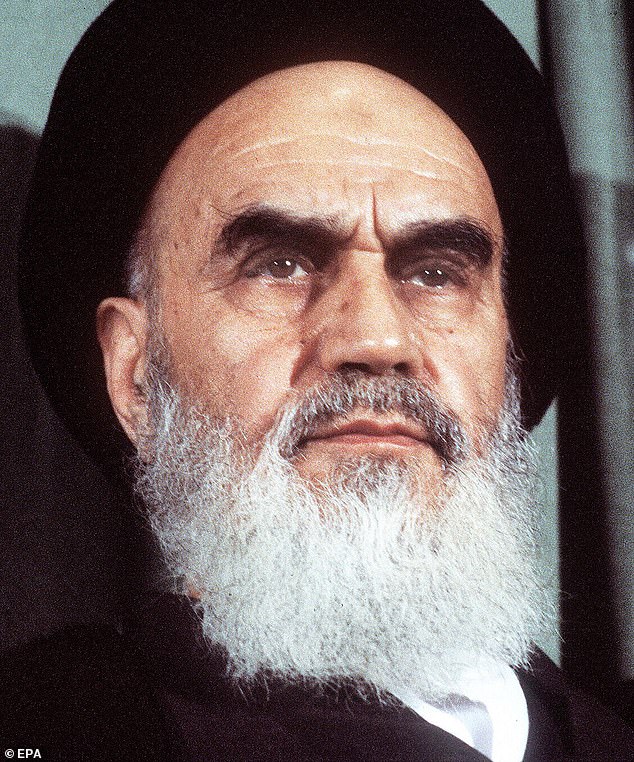

Ayatollah Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini was the supreme leader of Iran from 1979, after the Islamic Revolution, until his death ten years later.

Khomeini supporters march in Tehran in 1979, when the mullahs had taken power.

Similarly, back in 1967, Jordan invaded Israel, a disastrous move that saw it lose the territories of East Jerusalem and the West Bank. However, now Jordan has also stood by Israel to protect it from Iranian bombs. This new spirit of cooperation continues: just yesterday it emerged that both the Saudis and the United Arab Emirates had passed useful intelligence to the United States for use in the defense of Israel, and Jordan also agreed to allow US and Arab fighter jets “other countries” will use their airspace, in addition to sending their own planes.

One thing is clear. The rise of Iran – and its chilling proximity to a nuclear weapon – has brought old enemies closer together.

Iran now dominates a vast region from its borders with Iraq, through Syria and Lebanon, to the Mediterranean. Through its Yemeni proxies, the Houthis, and its own navy, it is causing chaos in the Red Sea, one of the world’s key maritime trade routes.

And it has turned the Palestinian cause into a strategic vehicle for its own ambitions through two other proxies, Hamas (Gaza) and Hezbollah (Lebanon). This chaotic and meddlesome statecraft has horrified other Muslim countries.

Middle Eastern history used to be “Israel against everyone else.” However, as a result of Iran’s behavior, this is no longer true. And this means that the prospects for long-term peace are, surprising as you may hear, bright.

To understand how all this has happened, it is necessary to go back to the very roots of Islam and the schism within it. In 610 AD, Muhammad revealed a new faith. When he died in 632 AD, he and Islam were all-powerful in Arabia, and within a century had subjugated an empire stretching from Central Asia to Spain.

For most of the time Israel has existed, Saudi Arabia, as one of the world’s leading Muslim nations and home to the holy city of Mecca, has been its implacable enemy, writes Stephen Pollard.

But Islam was divided over who should succeed the Prophet.

One faction argued that leadership should pass through their lineage. They became known as Shiites, from shi’atu Ali, which in Arabic means “supporters of Ali”, who was Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law.

The others, the Sunnis (followers of the ‘sunna’, or ‘way’ in Arabic), said leadership should be determined based on merit.

Ali was elected “caliph” (spiritual leader) in 656 AD, but within five years he was assassinated, enshrining a lasting division. Fast forward to 2024, about 85 percent of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims are Sunni, while 15 percent are Shia.

Two countries now compete for the leadership of Islam: Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shiite Iran. Since the mullahs took power in Tehran 45 years ago, mutual hatred between the sects has only grown.

As a minority within Islam, Shiites have historically been treated as subordinates in Sunni-dominated countries. But there has been significant growth in the Shiite population in the Gulf nations, to the point that in some they are almost a majority. This has increased anxiety among Sunni rulers over the growing power of Shiite Iran. In the Gulf States, such as the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain and especially Saudi Arabia, the Shiite threat – in other words, the threat from Iran – is considered existential.

Egypt, which has had a peace treaty with Israel since 1979, is also an enemy of the mullahs. In the 2006 Lebanon war between Israel and Hezbollah, Sunni countries behind the scenes wanted Israel to triumph, just as Jordan, Egypt and especially Saudi Arabia are now said to want Israel to destroy Hamas in Gaza.

The growing rapprochement of some Sunni countries materialized in the Abraham Accords of 2020, which normalized relations between the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Israel, and later between Morocco and Sudan.

There is, then, a logic in the ever-deepening alliances between the Sunni states and Israel. Arab nations understand that while Israel has no ambitions to dominate its neighbors, Iran seeks to control the entire Middle East.

It is necessary to emphasize that the vast majority of Sunnis and Shiites would prefer to continue with their lives rather than be involved in these disputes. But it is also true that if you do not understand this division, you cannot understand the Middle East at all.