Children born with Down syndrome 5,000 years ago were recognized as members of their communities, new research reveals.

DNA analysis of ancient human remains identified six people with the condition that causes learning disabilities or the more serious Edwards syndrome.

One case from a church cemetery in Finland dates to the 17th or 18th century, while the remaining five individuals, dating to between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago, were found at Bronze Age sites in Greece and Bulgaria, and in Iron Age sites in Spain.

The research team, whose findings were published in the journal Nature Communications, were able to obtain a wealth of additional information about the remains and burials.

Scientists discovered remains of oldest Down syndrome case ever recorded

The analysis has allowed the team to track the movement and mixing of people, and even discover ancient pathogens that affected their lives.

The researchers looked at data from 9,855 prehistoric and historical individuals and recorded the number and proportion of autosomal chromosomes.

An autosomal chromosome is the number of genes a person has: humans have 44 autosomal chromosomes and two chromosomes, but people who test positive for Down syndrome have an extra autosomal chromosome.

Down syndrome, a disease in which a person has an extra chromosome, today affects approximately one in every 1,000 births.

Until now, no systematic study of rare genetic diseases has been attempted.

While today people with Down syndrome can live long lives, often with the help of modern medicine, that was not the case in the past.

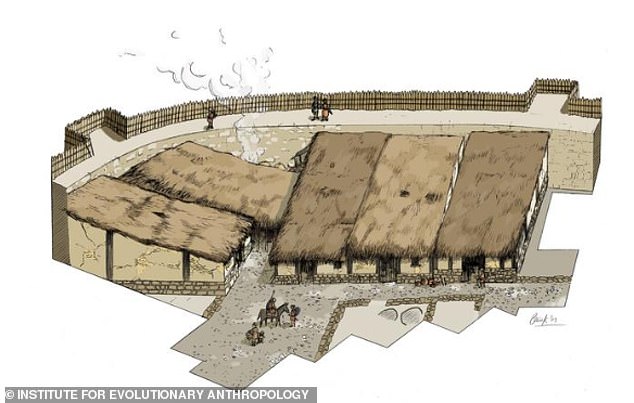

Researchers reconstructed what the Iron Age settlement in Las Eretas, Navarra, was like

Age estimates from skeletal remains showed that all six individuals died at a very young age, with only one child reaching around one year of age.

The five prehistoric burials were located within settlements and, in some cases, were accompanied by special objects such as colorful bead necklaces, bronze rings or sea shells.

People in Iron Age Spain normally cremated the deceased, but researchers noticed that one baby received an unusual burial beneath the floors in a decorated dwelling.

Dozens of other babies were discovered buried under the floor of nearby homes.

‘The main question was: What is so special about these children?’ Roberto Risch, archaeologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, said Science.

Lead author of the study, Dr Adam ‘Ben’ Rohrlach, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) in Germany, said: “These burials appear to show us that these individuals were cared for and appreciated as part of their ancient societies. ‘

Although the study aimed to find cases of Down syndrome, the researchers also discovered an individual with a different condition.

About 10,000 DNA samples were analyzed and one individual had an “unexpectedly high” fraction of ancient DNA sequences from chromosome 18 showing that he carried three copies of the chromosome.

Three copies of chromosome 18 are known to cause Edwards syndrome, a condition associated with more serious health problems than Down syndrome.

Remains of people with Down syndrome found in a Spanish Iron Age site

With an incidence of less than one case in every 3,000 births, Edwards syndrome also occurs much less frequently than Down syndrome.

The researchers found that in the six cases of Down syndrome detected and in the single case of Edwards syndrome, all individuals died before or shortly after birth, or at 16 months of age.

According to the study, researchers identified the individuals as being from Neolithic Ireland (3500 BC), Bronze Age Bulgaria (2700 BC), Greece (1300 BC), Iron Age Spain (600 BC) or post-medieval Finland (1720 BC). ).

The discovery was made in one of the Spanish Iron Age sites, in a town called Alto de la Cruz, near the Spanish city of Navarro.

“At the moment we cannot say why we found so many cases in these places,” Risch said.

‘But we know that they belonged to the few children who received the privilege of being buried inside houses after death. This is already an indication that they were perceived as special babies.’

As the number of DNA samples from ancient individuals continues to increase, the researchers plan to further expand their research in the future.

Dr. Kay Prüfer, also from MPI-EVA, coordinated the sequence analysis.

She said: “What we would like to learn is how ancient societies reacted to individuals who perhaps needed help or were just a little different.”