A former RAF engineer and his wife are signing up to become the first British couple to use a double suicide capsule.

Peter and Christine Scott, who have been married for 46 years, made the decision after former nurse Christine, 80, was diagnosed with early-stage vascular dementia several weeks ago.

The couple want to travel to Switzerland to die in each other’s arms in the death capsule, known as Sarco, to mark the end of their long and happy marriage.

Following an emotional family summit during which the couple shared their fears of suffering years of illness on a failing NHS and losing their home and life savings to pay the crippling costs of care, their son and daughter have reluctantly said they will respect their choice.

Peter, 86, and Christine, who have six grandchildren, are now in the process of registering with The Last Resort, a Switzerland-based organisation offering assisted dying at the Sarco, which opened in July.

Peter and Christine Scott, who have been married for 46 years, made the decision after former nurse Christine, 80, was diagnosed with early-stage vascular dementia several weeks ago.

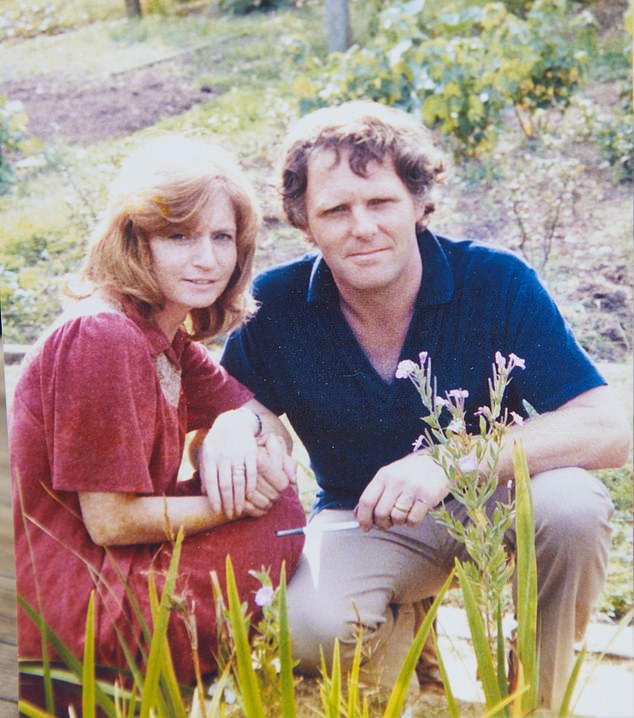

Peter and Chris Scott about 35 years ago

The capsule works by replacing the air, which is 21 percent oxygen and 79 percent nitrogen, with 100 percent nitrogen. This quickly renders the occupant unconscious and they then stop breathing in a process that takes less than ten minutes.

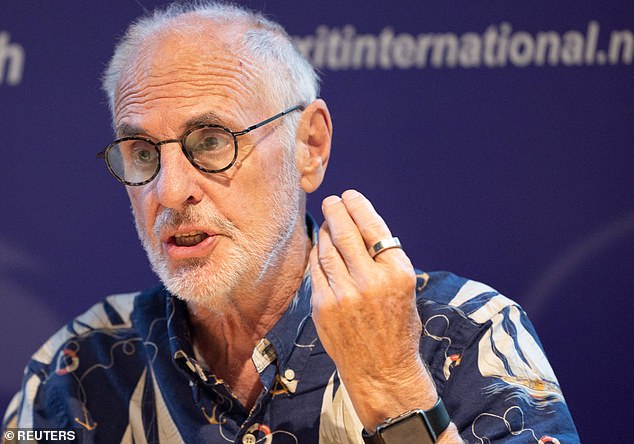

It has not yet been tested, but its creator, Australian Philip Nitschke (nicknamed Doctor Death by right-to-life opponents), hopes the first suicide will happen soon. The Scotts say they will wait until the machine’s new sister model is launched later this year.

In an extraordinarily frank interview at their home in the Suffolk village of Mellis, they revealed their plans in the hope of lending weight to the campaign to allow assisted dying in the UK, where it is illegal.

A Labour MP is now considering introducing a private bill after Sir Keir Starmer backed holding a free vote in the House of Commons on the issue.

Peter said: ‘We have lived long, happy, healthy and full lives, but here we are in old age and it does not bring us good results.

‘The idea of watching Chris’s mental abilities slowly decline in parallel with my own physical decline is horrifying to me.

Obviously, I would care for her to the point where she couldn’t, but she has cared for enough people with dementia during her career to be confident that she wants to remain in control of herself and her life. Assisted dying gives her that opportunity and she wouldn’t want to go on living without it.

Australian-born Philip Nitschke, nicknamed Doctor Death by opponents of the right to life, expects the first suicide to occur soon.

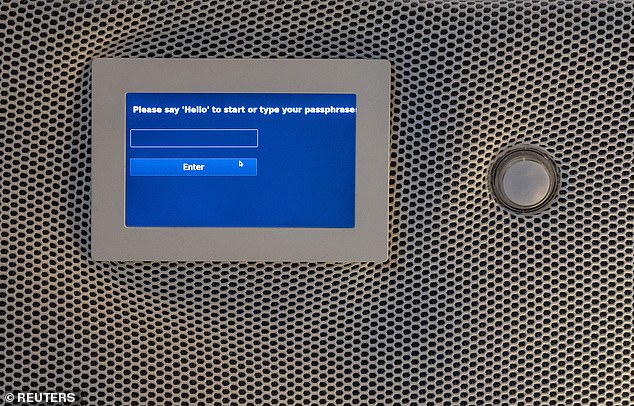

A view of the Sarco suicide machine, a 3D-printed capsule that gives the user maximum control over the moment of their death.

A view shows the login screen and the pure nitrogen release button on the Sarco suicide machine

‘We understand that other people may not share our feelings and we respect their position. What we want is the right to choose. I find it deeply depressing that we cannot do that here in the UK.

‘But if we consider the alternative, the chances of getting quick NHS treatment for the ailments of old age seem pretty remote, so we end up stuck with illness and pain.

‘I don’t want to go to a health care facility, lie in bed drooling and incontinent – that’s not what I call life.

“In the end, the government steps in and takes your savings and your house to pay for everything.”

Currently struggling with all the paperwork required for the complete application.

He is concerned about Christine’s request, as assisted suicide is more difficult to obtain for patients with dementia than for people with terminal cancer, for example.

The Sarco was invented at the request of British stroke victim Tony Nicklinson, who was left conscious but unable to move or speak after suffering a stroke.

He approached Nitschke to create a death capsule that could operate in the blink of an eye, the only communication he had left.

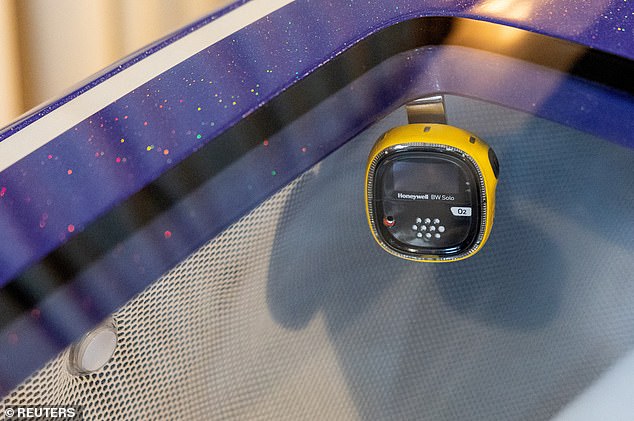

A person stands near the Sarco suicide machine during a presentation of The Last Resort in Zurich, Switzerland, July 17, 2024

View of the O2 detector and pure nitrogen release button on the Sarco suicide machine

Nicklinson, who pleaded with the courts to allow him to die legally but was denied his request, eventually starved himself to death in 2012, before Sarco was created.

The capsule works by replacing the air, which is made up of 21 percent oxygen and 79 percent nitrogen, with 100 percent nitrogen. This quickly renders the occupant unconscious and then causes them to stop breathing in a process that takes less than ten minutes.

A camera inside the capsule records his final moments and the images are handed over to a coroner.

The Sarco, which is being made using a 3D printer, is expected to be free of charge, but people must be able to pay for funeral homes to remove their body afterwards. Peter and Christine would like to be cremated and have their ashes repatriated and scattered in their local church cemetery.

The only additional cost currently known would be £16 for the liquid nitrogen used in the capsule, making it cheaper than other assisted dying clinics, which typically charge £10,000.

Speaking to the Mail on Sunday, Dr Nitschke confirmed his partner’s suicide capsule was ready for launch. He said: “The two-person capsule works exactly the same as the one-person Sarco, but there’s only one button so they’ll decide between them who’s going to press it. They can then hug each other and one of them will press the button.”

The Sarco was invented at the request of British stroke victim Tony Nicklinson, who was left conscious but unable to move or speak after suffering a stroke.

Christine has already planned her final days. ‘I would like to go for a walk with Peter in the Swiss Alps, along a river. I would have a beautiful fish dish for my last dinner and enjoy a great bottle of Merlot.

‘I would make a playlist that included Wild Cat Blues and Cliff Richard’s The Young Ones and I found a poem called Miss Me But Let Me Go, which sums up exactly how I feel.’

Unsurprisingly, the 1930s song Goodbye by American songwriter Gordon Jenkins will be on Peter’s playlist. A former RAF aircraft engineer, he worked in the aviation industry around the world before returning to his native East Anglia to forge a second career as a careers adviser.

He and Christine fell in love at first sight after meeting at a jazz club. She was a nurse and had a young daughter from her first marriage. After they married, they had a son together.

Their children have been encouraging them to move into a retirement community, but the couple are determined to make assisted dying a possibility.

Christine says: “It’s a beautiful life, but I have this diagnosis and it has crystallised our thinking. Medicine can slow down vascular dementia, but it can’t stop it. The moment I thought I was losing it, I said, ‘This is it, Pete, I don’t want to go on.'”

And he added: “I told him: ‘You decide and I will be with you’. For me, death is not a problem.”

‘I would give him a big hug and say, “I hope to see you later.”