Table of Contents

Friday

Outdoor theater on the Coachella stage

15:40 – Recording Safari 16:15 – Fade Out

16:45 – Young Miko 17:25 – L’Impératrice

6:00 pm – Sabrina Carpenter 6:45 pm – Deftones

19:35 – Lil Uzi Vert 20:10 – Everything always

21:05 – Featherweight 22:15 – Justice

23:20 – Lana del Rey

SonoraGobi

13:00 – Doom Dave 14:00 – Cimafunk

14:00 – Vomit 15:10 – Kokoroko

14:50 – Narrowhead 16:20 – Sid Sriram

3:50 pm – overnight trip home 5:20 pm – Chappell Roan

4:50 pm – The Beths 6:45 pm – Brittany Howard

5:55 pm – Eartheater 8:00 pm – Neil Francis

8:00pm – Black Country, New Road 9:15pm – Chloe Bailey

9:05 pm – Clown Core 10:30 pm – Suki Waterhouse

10:20 p.m. – Son Rompe Pera

Mojave Sahara

14:10 – DAYSONMERKET 14:00 – Sincerely, Manolo

3:15 pm – Shop at the mall 3:00 pm – Skin to skin

4:30 pm – The Japanese House 4:00 pm – Cloonee

5:40 pm – Faye Webster 5:20 pm – Ken Carson

18:55 – Tinashe 18:30 – Skepta

8:20 pm – Yoasobi 7:45 pm – Bizarrap

21:50 – Hatsune Miku 21:15 – Peggy Gou

23:15 – Anti Up 22:45 – ATEEZ

12:00 am – Steve Angello

Yuma Quasar

13:00 – Keyspan 17:00 – Patrick Mason

2:00 pm – Ben Sterling 7:15 pm – Green Velvet

15:00 – Miss Monique 20:30 – Honey Dijon

16:15 – Innellea 21:45 – Honey Dijon x Green Velvet

5:30 pm – RUBIO: ISH

18:45 – Kevin de Vries x Kolsch

20:15 – ANOTR

21:45 – Adriatic

23:15 – Gorgon City

Saturday

Outdoor theater on the Coachella stage

15:45 – Jaqck Glam 16:05 – Gabe Real

4:45 pm – Santa Fe Klan 5:00 pm – Vampire Weekend

6:05 pm – Sublime 6:10 pm – Blxst

19:40 – Blur 19:25 – Jon Batiste

21:25 – Without a doubt 20:40 – JUNGLE

23:40 – Tyler, the Creator 22:40 – Gesaffelstein

SonoraGobi

13:00 – Triste Juventurd x TOTEM 13:15 – Elusive

14:00 – Military pistol 14:05 – Erika de Casier

2:55 pm – Girl Ultra 3:10 pm – Young Parents

15:55 – The Aquabats 16:20 – Thursday

5:05 pm – The Addicts 5:30 pm – The Last Supper

6:15pm – Sonoran Depression 6:45pm – Palace

19:15 – The Red Pears 20:00 – Punto Never Oneohtriz

20:15 – bar italy 21:15 – San Levante

21:15 – Brutalism 3000 22:25 – Kevin Kaarl

23:20 – Orbital

Mojave Sahara

14:00 – ANIKA KAI 14:00 – Loboman

15:05 – Kenya Grace 15:10 – Starrza

4:10 pm – RAYE 4:30 pm – Destroy Lonely

5:25 pm – Kevin Abstract 5:40 pm – Purple Disco Machine

6:50 pm – Bleachers 7:10 pm – Grimes

20:05 – Charlotte de Witte 20:30 – Ice Spice

21:50 – Coi Leray 21:30 – ISOKNOCK

22:45 – The drums 22:50 – LE SSERAFIM

23:55 – Dom Dolla

Yuma Quasar

13:00 – Quimonos 17:00 – Carlita

14:00 – Maz 19:15 – Michael Bibi

3:00 p.m. – Mahmut Orhan

4:15 pm – Reprimand

17:30 – Will Clarke

18:45 – Ame x Marcel Dettmann

20:00 – Reinier Zonneveld

21:30 – Patrick Mason

11:00 p.m. – The Blessed Virgin

No Doubt will reunite on stage at Coachella on Saturday, April 11; seen above in 2015 in Los Angeles

Sunday

Outdoor theater on the Coachella stage

14:50 – LUDMILLA 15:55 – Tiffany Tyson

4:05 pm – YG Marley 5:05 pm – Renee Rapp

5:25pm – Carin León 6:25pm – La Rosa

18:50 – Bebe Rexha 19:50 – Khruangbin

20:20 – J Balvin 21:30 – Jhene Aiko

22:25 – Doja Cat

SonoraGobi

13:00 – Argenis 14:15 – waveGroove

13:55 – jiuujiuu 15:30 – Mdou Moctar

3:00 pm – Bb Trickz 4:40 pm – Jockstrap

3:55 pm – weak horse 5:50 pm – Olivia Dean

4:50pm – Hermanos Gutiérrez 7:00pm – Dos Conchas

6:05 pm – Eddie Zuko 8:20 pm – Barry can’t swim

19:05 – LATIN MAFIA 21:40 – ATARASHI GAKKO!

8:15 pm – Mandy, Indiana

9:20 pm – Toughest Guy

Mojave Sahara

2:00pm – Honey Roots 2:00pm – Bones

15:00 – FLO 15:00 – Tita Lau

4:10 pm – Recovery Sunday 4:00 pm – SPINALL

5:20 pm – 88 FUTURES Rising 5:10 pm – AP Dhillon

18:55 – Victoria Monet 18:20 – NAV

20:10 – Topics 19:45 – Anyma

21:25 – Lil Yachty 21:15 – DJ Snake

22:40 – BICEP 22:55 – John Summit

Yuma Quasar

1:00 pm – JOPLYN 4:00 pm – Shop at the mall

2:00 pm – DJ Seinfeld 6:15 pm – Jamie XX x Floating Points x Daphni

3:00pm – Flight Facilities

16:30 – Eli and Fur

6:00 pm – Adam Ten x Mita Gami

19:30 – Carlita

9:00 p.m. – Folamour

10:30 p.m. – ARTBAT

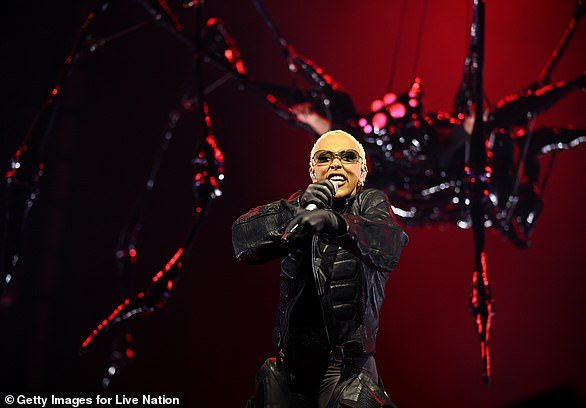

Doja Cat is scheduled to perform on stage at Coachella on Sunday, April 12; seen in 2023 in San Francisco