A lung infection lurking in drinking water has killed dozens of Americans and sent hundreds to the emergency room, a new official report warns.

From 2015 to 2020, the bacterium Legionella caused 184 outbreaks in the United States, resulting in 786 illnesses, 544 hospitalizations, and 86 deaths.

The CDC looked at other disease-causing pathogens and resulting outbreaks, including norovirus and the bacteria Shigella, bringing the total number of water-related disease outbreaks to 214.

The new CDC report said most outbreaks and illnesses — 79 percent and 52 percent — could be traced back to public water systems that supply tap water to homes, office buildings and hospitals.

Outbreaks caused by legionella specifically increased after 2015, according to the report’s authors, who urged public health departments across the country to strengthen their capacity to detect water-related disease threats as they arise.

CDC officials investigated a total of 214 disease outbreaks linked to pathogens lurking in drinking water, including legionella, shigella and norovirus

The CDC investigators said: ‘During 2015-2020, Legionella-associated outbreaks continued to increase and were the leading cause of nationally reported drinking water-related outbreaks, hospitalizations and deaths.

“This trend was primarily influenced by the increasing number and proportion of Legionella-associated outbreaks associated with community and non-community water systems.”

Legionella bacteria is spread when a person inhales aerosols that have been contaminated with it, including from water towers, air conditioners, hot and cold water systems, humidifiers, and hot tubs.

The microscopic pathogen can cause Legionnaires’ disease, a potentially fatal pneumonia, or Pontiac fever, a less serious illness.

About one in 10 people who get sick will die. The chances of death are higher when the disease is contracted in a hospital, where at least one in four die.

Last year, 71-year-old Barbara Kruschwitz of Massachusetts died of Legionnaires’ disease just a week after staying at the Mountain View Grand Resort in Whitefield.

Her husband Henry said she had been swimming in the pool and hot tub at the resort, but he had not.

He said: ‘Her heart had stopped and she could not be revived. And – that’s about as much as I can say.’

Early symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease include fever, loss of appetite, headache, lethargy, muscle aches and diarrhea. Severity can range from a mild cough to fatal pneumonia, and early treatment of infection with antibiotics is key to survival.

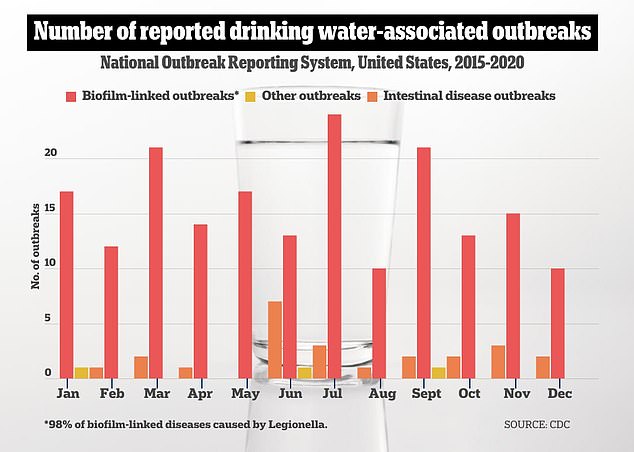

Reported outbreaks included 187 biofilm-associated, 24 enteric disease-associated, and three other unknown sources. Biofilms form on surfaces in water systems and act as an ideal reservoir for bacteria to grow and spread

Legionella can colonize and grow in complex communities of microorganisms called biofilms that form on surfaces in water systems. Once there, the bacteria seep into the water and become aerosolized.

Plumbing systems, especially those associated with hot water, such as hot water tanks and distribution pipes, can also serve as reservoirs for legionella bacteria to multiply. From there, it can contaminate water in pipes. Stagnant or low-flow areas in pipes also promote the growth of legionella.

Water treatment plants typically use a disinfectant such as chlorine to clean the drinking water system. In 79 outbreak reports, chlorine was listed as the disinfectant used, while 99 reports did not include the type of disinfectant or treatment used.

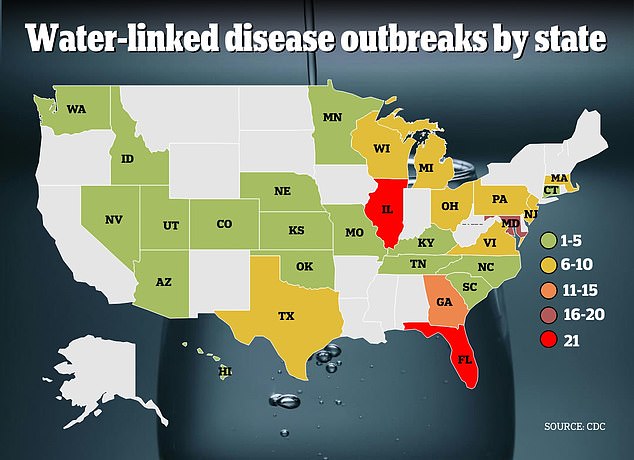

In the new report, CDC officials compiled reports of 214 outbreaks across 28 states, including those caused by legionella, norovirus, Shigella, Campylobacter, E. coli and other unspecified pathogens. In total, there were 2,140 illnesses, 563 hospitalizations, and 88 deaths associated with these pathogens.

Of these total outbreaks, 187 involved pathogens growing in biofilms and entering the water supply. And Legionella growing in biofilms caused the largest number of outbreaks, 184, of them all.

Most disease outbreaks were linked to public water systems, which supply most homes and are monitored by city governments.

Seventeen outbreaks were linked to private water systems, such as wells that some people use to supply their homes. Most of the infections were reported in Illinois, Florida and Maryland.

The number of legionella outbreaks fluctuated during the study period, from 14 in 2015 to 31 in 2016, then lower to 30 in 2017, up again to 34 in 2018, down to 33 in 2019 and 18 in 2020.

Scientists did not provide a possible explanation for the peaks and troughs.

However, Covid-era lockdowns, stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures led to reduced human activity in public spaces such as offices, hotels and recreational facilities where Legionella is most commonly found, limiting the bacteria’s ability to grow and spread.

Legionella bacteria can multiply significantly in hot water systems in large buildings such as hospitals due to several factors, such as water temperatures below 50 degrees Celsius, areas where the water does not flow well and collects, the presence of amoebas and other bacteria, and materials used in the pipes.

Hospitals, long-term care facilities, and rehab clinics were the most common sources of exposure, accounting for 113 of the 214 total outbreaks.

While the CDC report stops at 2020, local reports of outbreaks from 2023 to 2024 suggest legionella bacteria may pose a greater threat to public health today than they did three or four years ago.

For example, northern Minnesota is grappling with an outbreak that has sickened 15 people and sent 11 of them to the hospital since last April. So far no one has died.

In 2023, the statewide tally was 134 cases related to Legionnaires’ disease, including six deaths.

Also last year in New Jersey, health officials reported that 21 people in Middlesex County and 20 people in Union County became ill and tested positive for legionella. The tests were carried out between August 3 and October 24, when the symptoms occurred.

The state usually records 250 to 375 cases of Legionnaires’ disease annually.