The largest saltwater lake in the United States has been drying up, raising health fears as a “scary” level of “toxic dust” spreads across Utah.

Two recent studies have suggested that a dangerous level of toxic dust is spreading throughout the Salt Lake Valley as the Great Salt Lake continues to see rising and falling water levels, according to The Salt Lake Tribune.

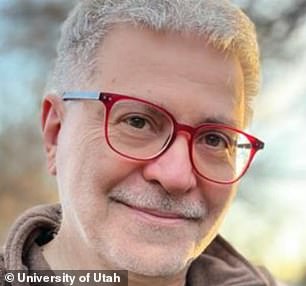

“What we’re really concerned about here is an increase in the rate of cancer in people who would be exposed to this over a long period of time,” Professor Kevin Perry of the University of Utah told The Tribune.

Although the research “doesn’t say the sky is falling and we’re all going to die,” it does show “concern,” according to Professor Kerry Kelly of the University of Utah.

“It’s definitely worth further examination,” he told The Tribune.

The Great Salt Lake is a terminal lake, meaning it receives runoff from a drainage basin in northern Utah and three other states. The only way for water to leave the lake is through evaporation.

Studies found a “frightening” amount of arsenic and other chemicals in the dust coming out of the lake, which millions of residents breathe, according to The Tribune.

Two recent studies have suggested that a dangerous level of toxic dust is spreading through the Salt Lake Valley as the Great Salt Lake continues to see rising and falling water levels.

One of the studies suggests that the dust coming out of the lake is more dangerous than other dust flying around the Valley and could pose a dangerous health effect, even though the government says the levels are fine.

But research samples taken from the Weber River, which flows into the Great Lake, suggested there is a harmful level of toxins in the sediment.

However, the Utah Division of Air Quality said the level of dust deposited compared to what a person inhales can be different, and its analysis of PM10 dust samples, which are smaller than a human hair, showed no no increase in severity, according to The Tribuna.

But Kelly, Perry and fellow Utah professor Diego Fernandez believe more studies need to be done, and done quickly.

“We really need to think about how to best create a sampling network that can capture all of these dust events so we can know how frequent they are and how bad they really are,” Perry, known as “Dr. Dust,” told the outlet. .

“What we’re really concerned about is an increase in the rate of cancer in people who would be exposed to this over a long period of time,” said Kevin Perry, a professor at the University of Utah. Diego Fernández believes that more studies are needed to know the true extent of toxicity

Although the research “doesn’t say the sky is falling and we’re all going to die,” it does show “concern,” according to Professor Kerry Kelly of the University of Utah. “It’s definitely worth continuing to look at,” he said.

The Great Salt Lake is an emerging source of dust, Perry said, and his most recent study found that sediments in dust can become more bioavailable and potentially harmful if breathed in, especially during a dust storm.

“We need to know the concentrations that people are actually breathing to know if they are harmful or not,” he said.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have that information,” he said.

Part of the reason scientists don’t have access to that information is because there are no monitoring systems to track PM10 particles, which the large lake primarily has.

Although the Division of Air Quality allocated $275,000 for five new monitors, none of them have been installed, according to The Tribune.

The government agency is in the process of placing monitoring systems near major populated areas, but “they do not have monitors that more frequently capture dust from the Great Salt Lake,” a spokesperson told The Tribune.

The second study found similar results to Perry’s study and looked for concentrations of copper, thallium, arsenic, mercury, lead and zinc, which can be toxic at high levels.

Cooper remained elevated compared to previous studies. Arsenic was also “significantly higher” in areas of Gilbert Bay west of Antelope Island, according to The Tribune.

Thallium also increased, and lead and zinc increased in some areas.

Scientists believe the best way to combat toxic dust is to keep the lake filled with water to keep the sediment buried.

They also believe they need “sampling of where the dust is going, like Syracuse, Ogden and Layton,” Perry said.

And Fernández insists that more studies need to be carried out to know the true duration of the poison and how it will affect residents in the long term.