A small ranching community in Colorado has been torn apart as newly released wolves have slaughtered a staggering amount of livestock in just a few days.

Conway Farrell, a rancher in Grand County, about 30 minutes from the Rocky Mountains, said his father discovered a dead calf Sunday, the fifth cattle lost in 11 days.

‘Yes, I’m screwed. “Everyone here is getting nervous and at their wits’ end,” Farrell told the Coloradoan. “It feels like you’re getting slapped every damn minute.”

In December, state wildlife officials released wolves into a remote forest in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. The release arose from a voter-approved reintroduction program that aims to repopulate the endangered species.

Now, Farrell said tensions have risen between ranchers and Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials in the city.

“We see them in the supermarket and they’re all sitting there trying to act like we’re all happy, but what’s going on behind the scenes every day is tremendously disturbing,” he said.

Grand County rancher Conway Farrell said his father discovered a dead yearling, or baby cow, on Sunday, the fifth cattle lost in 11 days.

Farrell, who was previously hesitant to speak up, decided he had to as his frustration with the current problem had increased. (pictured: the dead calf found on Ferrell’s land)

Proposition 114 required the Parks and Wildlife Commission to “develop a plan to restore and manage gray wolves in Colorado, using the best available scientific data” and “hold hearings across the state to acquire information that would be considered in developing of said plan,” according to CPW.

The state wildlife agency has a policy that prevents them from sharing the movements of wolves based on the number of their collars, including one wolf that died.

Ferrell and his fellow ranchers decided to use their own hunting cameras over the past few months to track the predators on their own.

He said he and other ranchers have “high confidence” that wolf 2309 and wolf 2312 of the Weneha pack are responsible for the recent attacks.

He added that Colorado Parks and Wildlife Director Jeff Davis has created a “disgustingly huge disconnect” between ranchers and wildlife officials.

“Once Governor Polis opened that door to release the first wolf, to me that means they are the responsibility of the state,” he said.

‘But if you annoy them, the agreement says that the State is not responsible for anything and that it is your responsibility. ‘How fair is that?’

On Tuesday, the Colorado Department of Agriculture said it will dedicate up to $20,000 to ‘non-lethal deterrent measures’ for the Middle Park Cattlemen’s Association, including night patrols and herd protection for ranchers and their livestock.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife told the Coloradoan, “CPW will again review this specific situation with USFWS to ensure actions comply with all state and federal laws and regulations and the Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan.”

Ferrell noted that it has also not been easy to deal with the presence of agents around Kremmling, a small town with a population of only 1,500 inhabitants.

“We can’t even go to school to pick up our kids without running into one of these guys,” he explained.

In December, packs of wolves were released as part of a voter-approved reintroduction program that aims to repopulate the endangered species.

Ferrell said tensions have risen between ranchers and Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials since the wolves were released.

“I don’t believe in stress, but I’m starting to.”

‘Just get up and go to work. Yes, you have problems but you solve them every day. But they have us to the point where we cannot solve the problem we have,’ he added.

In December, two juvenile female wolves, two males and one adult male, were released after being captured in Oregon and came from Oregon’s Five Points, Noregaard and Wenaha packs.

Before being released, the CPW They collected genetic material (tissue and blood samples) before fitting each animal with a GPS satellite collar for tracking.

The wolves also received vaccines and were treated against endoparasites and ectoparasites.

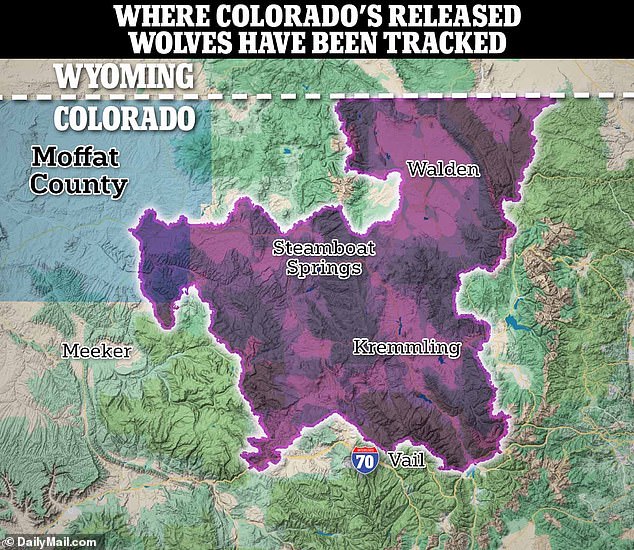

According to the Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan, wolves can travel up to 140 miles from where they were released.

In February, Wyoming ranchers became concerned about the presence of wolves after they were released near the state line.

“Wolves can travel 50 miles a day, (so) that doesn’t surprise me at all,” Howard Cooper told Cowboy State Daily.

Wolves have been sighted in Walden, just 20 miles from Wyoming, meaning the predators could theoretically cross into the Cowboy State.

Like Ferrell, Cooper opposes the reintroduction of gray wolves to the neighboring state and has even backed a lobby group that aims to prevent new wolf releases.

In Colorado it is illegal for the general public to hunt or kill wolves, as they are protected by the federal government.

But by crossing the line, a wolf that enters Wyoming’s 53-million-acre “predator zone” – which covers about 85 percent of the state – goes from being an “endangered” animal to one that You can shoot him as soon as you see him.

In March, a pack of recently released wolves was tracked making their way toward state lines and approaching the Wyoming border.

Two wolves were confirmed to have recently entered Moffat County, located less than 50 miles from the Wyoming border.

In February, ranchers in Wyoming became concerned about the presence of wolves after they were released near the state line.

In the state of Colorado it is illegal for the general public to hunt or kill wolves, as they are protected by the federal government.

John Michael Williams, a Colorado resident who runs the ‘Colorado Wolf Tracker’ Facebook page estimated the duo could cross the border within four to six weeks of being spotted.

‘If you had a crystal ball, what would you think? I think at some point in the next four to six weeks we will have a crossover, or maybe a couple of crossovers.’

“And I think we’re going to see some of them get shot,” Williams said. Cowboy State Journal.

The Colorado Sun reported that at least one wolf died after crossing into Wyoming.

The publication cited reports from ranchers and other interested parties, but Wyoming officials declined to confirm the death.

Rather, they claimed the information was confidential under an 11-year-old state policy aimed at masking the identity of people who legally kill wolves in the state.

Reintroduction has proven to be a contentious point. Gray wolves were nearly hunted to extinction in the 20th century.

In 1905, the federal government infected animals with mange. A decade later, Congress passed a law requiring their removal from federal lands.

By 1960, the animals had been practically exterminated from their former habitat, under the same pretext that they represented a threat to livestock and large game.