Forget expensive DNA testing and MRIs – you can test your age-related health in the comfort of your home.

Mayo Clinic researchers found that the amount of time a person was able to balance on one foot indicated key measures of the health of their bones, muscles and nerves.

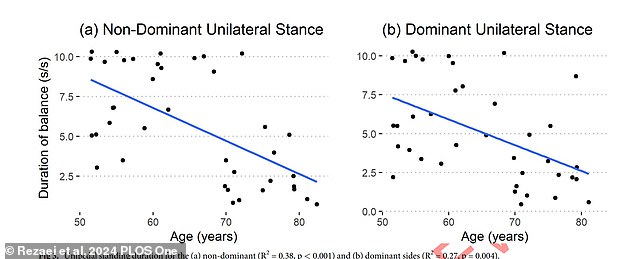

The average 50-year-old was able to balance for about nine seconds, while the average 80-year-old was closer to 3 seconds.

Standing on one foot requires your body to perform a series of complex tasks at the same time.

It requires combining information from small organs inside the ear that control balance, visual signals from the eyes, and multiple large muscle groups in the legs and trunk to stay upright.

This, the researchers say, makes it a simple and effective way to measure age-related changes in muscles, bones and nerves.

In 2019, the late Daily Mail contributor Dr. Michael Mosley discussed the benefits of practicing balancing on one leg.

He noted that if you can do it for ten seconds with your eyes closed, you should be in good health, regardless of your age.

The wellness world has turned longevity testing into an industry. Reality TV star Kim Kardashian made headlines last year for promoting full-body MRIs to screen for a host of age-related diseases.

Popular biohackers like Bryan Johnson measure everything from cholesterol to nighttime erections to get an idea of how they compare to other people their age.

But scientists, like those on the Mayo Clinic team, are looking for simpler, more cost-effective ways to give patients insight into their health, both at home and in the doctor’s office.

Science has long known that muscles, bones, and movement deteriorate as we age.

It is not clear whether strength, balance, or gait begin to decline first and therefore what is the best measure of age.

So researchers at the Mayo Clinic attempted to determine this by conducting a battery of movement-related tests on 40 participants between the ages of 50 and 80.

They excluded obese people and people with pre-existing conditions that would affect their balance or stride and created tests that measured their gait, balance and strength.

“I managed eight seconds, not bad for a 62-year-old,” said Dr Michael Mosley (pictured)

For the strength tests, they used a custom device to test participants’ grip strength and a test that involved extending the knee as quickly as possible.

In the walking test, participants walked forward and backward over a 26-foot course at a comfortable speed while wearing motion capture sensors three separate times.

They used measures such as speed, step length and stride length.

Finally, in the balance test, individuals were tested on two legs and one leg.

For the two-leg test, they were asked to look forward, once with their eyes open and once with their eyes closed, and place their feet on two force plates, which measure the force someone exerts on the ground.

For the one-leg test, physical therapists told participants to stand with their arms in whatever position was comfortable for them.

They were then timed lifting and holding one leg at a time, for as long as they could maintain balance.

The two graphs show the amount of time someone was able to balance on their dominant and non-dominant feet, one at a time. On the non-dominant foot, the amount of time participants could stand decreased by 2.2 seconds per decade.

The way they walked didn’t change significantly as people aged, but the amount of time their balance, grip, and knee strength changed. The findings were published in the journal Public Science Library.

The measure that changed the most with age was balance on one leg. The researchers said this is a good measure of frailty, independence, likelihood of falling and nerve damage in the extremities.

With each decade of age, the amount of time a person could stand on their non-dominant leg decreased by 2.2 seconds; Therefore, if a 50-year-old could balance for 15 seconds, a 60-year-old could balance for 12.8 seconds.

For the dominant leg, the amount of time they could endure decreased by 1.7 seconds per decade.

The researchers said this test could be implemented in doctors’ offices as an inexpensive, low-tech way to assess bone strength and aging.

They said: ‘This finding is significant because this measurement does not require specialized expertise, advanced tools or measurement and interpretation techniques. It can be done easily, even by individuals themselves.’

Having an idea of where your neuromuscular health is can help you create a wellness plan that works for you.

For example, if strength or bone mass is lacking, an individual could incorporate some light weight training into their routine to try to regain some strength.

The researchers concluded that these results “may help optimize these training and maintenance programs to improve balance and strength in the elderly population, thereby postponing or avoiding disability.”