Reports suggest that a medicinal gas used in thousands of hospitals across the United States may be causing cancer.

Ethylene oxide (EtO) is a colorless, odorless gas commonly used to clean hospital equipment, including ventilators, surgical kits, catheters, and gowns.

But studies suggest that when regularly inhaled, the chemical can cause harmful mutations in cells and increase the risk of cancer, including blood, stomach and breast cancer.

There are particular concerns for those who live near sterilization facilities where the gas can remain in the air for hours, repeatedly exposing people.

The EPA warned that there were 88 facilities using gas in 2022, and 23 of them had emissions levels in the local area that concerned officials.

Affected states included Missouri, Nebraska, Colorado, Utah, Oklahoma, Texas and Florida, among others.

Ural Grant was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer in 2019. He has lived in Memphis for 35 years.

Among them is Sterilization Services of Tennessee, which has raised alarm among residents of the nearby Mallory Heights Community Development Corporation in south Memphis.

Vera Holmes, president of the area’s CDC, is campaigning for action against polluted air.

She said ABC News: ‘Many people I know within my family who live in this area have died of cancer or now have cancer.’

One of the residents is Ural Grant, who has lived in Memphis for 35 years. Mr Grant was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer in 2019 and was told ABC News that many of their neighbors also have cancer.

“I thought this was my American dream: to have a home, to have a house,” he said. “But then it became kind of an American nightmare.”

Grant said he can’t afford to move because of his mounting medical bills, like many other residents of the working-class neighborhood.

EtO is used in many facilities to sterilize medical equipment such as ventilators, catheters, and syringes.

KeShaun Pearson, president of Memphis Community Against Pollution, told ABC News: ‘(Memphis) as a whole has an F in air pollutants and air quality, and 98 percent of the particular matter that makes up the pollution is here in south Memphis. ‘

Pearson believes the prevalence of toxic emissions in predominantly black neighborhoods is a sign of racial injustice.

‘That is not a coincidence. That’s by design. “This area specifically has been designed to be a place where people’s lives can be sacrificed,” she said.

The border city of Laredo, Texas, faces a similar battle.

The city of 250,000 residents, most of whom are working class and Hispanic, is home to several industrial warehouses, including Midwest Sterilization Corporation.

The company sterilizes up to 40 percent of the country’s medical kits. “This is one of the largest storage areas in the city,” Víctor Treviño Jr, a local lawyer who has lived in this city his entire life, told ABC News.

“We have residential areas right next to this industrial area, a couple of kilometers away.”

‘Laredo has a 95% Hispanic population. We have one of the highest poverty rates in the state. This is really a crisis for us right now.”

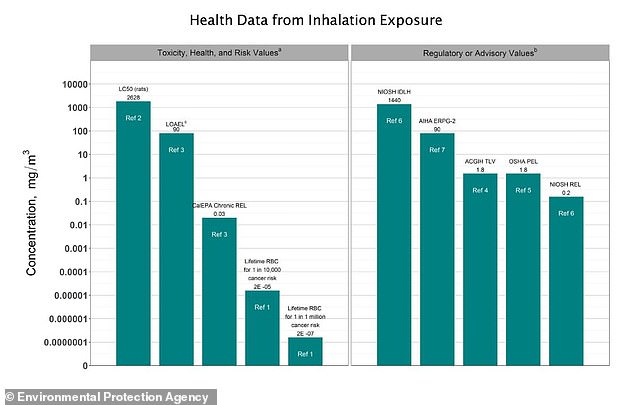

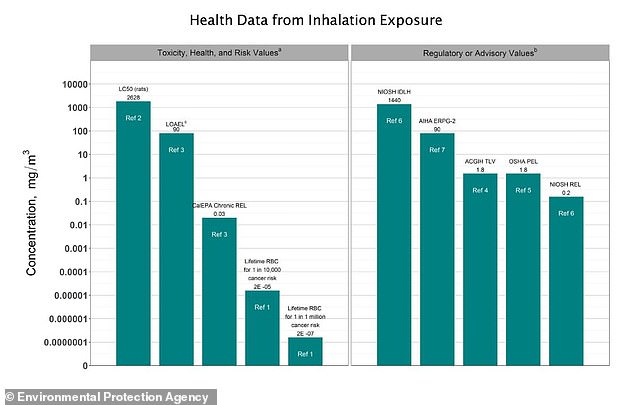

The EPA has found that EtO exposure “has been shown to cause lymphoid cancer and tumors of the brain, lung, connective tissue, uterus, and mammary gland in animals exposed to ethylene oxide by inhalation.”

The agency has concluded that EtO “is carcinogenic to humans via inhalation exposure.”

For the first time in 50 years, the EPA last month issued new rules that will require commercial sterilization using EpO to reduce emissions by more than 90 percent.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan said: “We have arrived at a historically sound rule that will protect the communities most at risk from toxic air pollution while ensuring there will be a process that safeguards the critical supply of sterile medical equipment. of our nation.”

Meanwhile, activists like Ms. Holmes continue to push to remove facilities that use EtO from their communities.

“People are tired,” he said. ‘They are afraid to speak or express themselves. But it’s up to us as leaders to step in and say, “Hey, we hear you and we can make some things happen.” It just takes the right team to do the right thing.”‘