From unexplored trenches to the Bermuda Triangle, the world’s oceans are full of unsolved mysteries.

But one of the strangest questions is why a vast swath of the Atlantic Ocean has suddenly begun cooling at record speeds.

Through March, the central Atlantic had experienced its warmest weather event since 1982, with highs of 30° (86°F).

However, this was followed by a dramatic change in temperature, with surface water temperatures dropping below 25 °C (72 °F), and scientists still don’t know what caused it.

Michael McPhaden of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said Living science“We’re still scratching our heads wondering what’s really going on.”

Scientists have been left baffled as to why a large area of the Atlantic Ocean (pictured) suddenly began cooling at an unprecedented rate.

Scientists are currently intensively monitoring the stretch of water, which stretches a few degrees on either side of the equator between Brazil and the coast of East Africa.

It’s not just that this region, known as the central equatorial Atlantic, is cooling, which is unusual, but rather the speed of the change.

Each year, the central equatorial Atlantic oscillates through its temperature cycle, reaching its warmest points in March and April before cooling in the summer.

However, beginning in June, surface water temperatures began to fall at an unprecedented rate.

In mid-June, temperatures in this region were 0.5 to 1.0 °C (0.9 to 1.8 °F) cooler than average for this time of year.

In June, a large area of the central equatorial Atlantic unexpectedly reached temperatures well below average for this time of year without any apparent cause.

Water temperatures have begun to rise toward normal levels, but scientists are puzzled as to what caused the sudden cooling in the first place.

Dr McPhaden says: “It could be some transient feature that has developed from processes we don’t understand very well.”

Generally, cooler summer waters in the Atlantic are associated with stronger trade winds blowing over the equator.

These strong winds drag warmer surface waters into the cooler deep ocean waters and bring them to the surface in a process called equatorial upwelling.

In a normal year (pictured), strong winds over the equator sweep warm water away from the surface and allow cooler water to rise from below (illustrated in purple).

What makes this year so unusual is that winds over the cold region (pictured) are actually weaker than normal, a condition normally associated with warmer temperatures.

However, winds in the rapidly cooling region were actually weaker than normal this year, typically a sign that warmer waters are coming.

There were some strong winds in early May that may have started the cooling process, but Dr McPhaden notes that “they haven’t increased as much as they have decreased the temperature.”

Dr McPhaden says that while man-made climate change cannot be ruled out as a cause, it is unlikely to be responsible.

“At first glance, this is simply a natural variation in the climate system in the equatorial Atlantic,” says Dr McPhaden.

A half-degree variation on either side of the average may not seem like cause for much fuss, but scientists are keeping a close eye on this region of the ocean.

The reason is that prolonged cooling in the central equatorial Pacific could be a sign that an Atlantic La Niña event is on the way.

The abnormally rapid cooling followed the warmest weather event since 1982, when temperatures reached 30°C.

The concern is that this cooling event could evolve into an Atlantic Niña event, which is defined by three months of cooler than average temperatures.

Like their better-known cousins, the Pacific El Niño and La Niña, Atlantic El Niño/Niña are the intense peaks and valleys of ocean warming and cooling cycles.

If below-average water temperatures persist for three months, this would be enough to classify it as an Atlantic La Niña, something that has not happened since 2013.

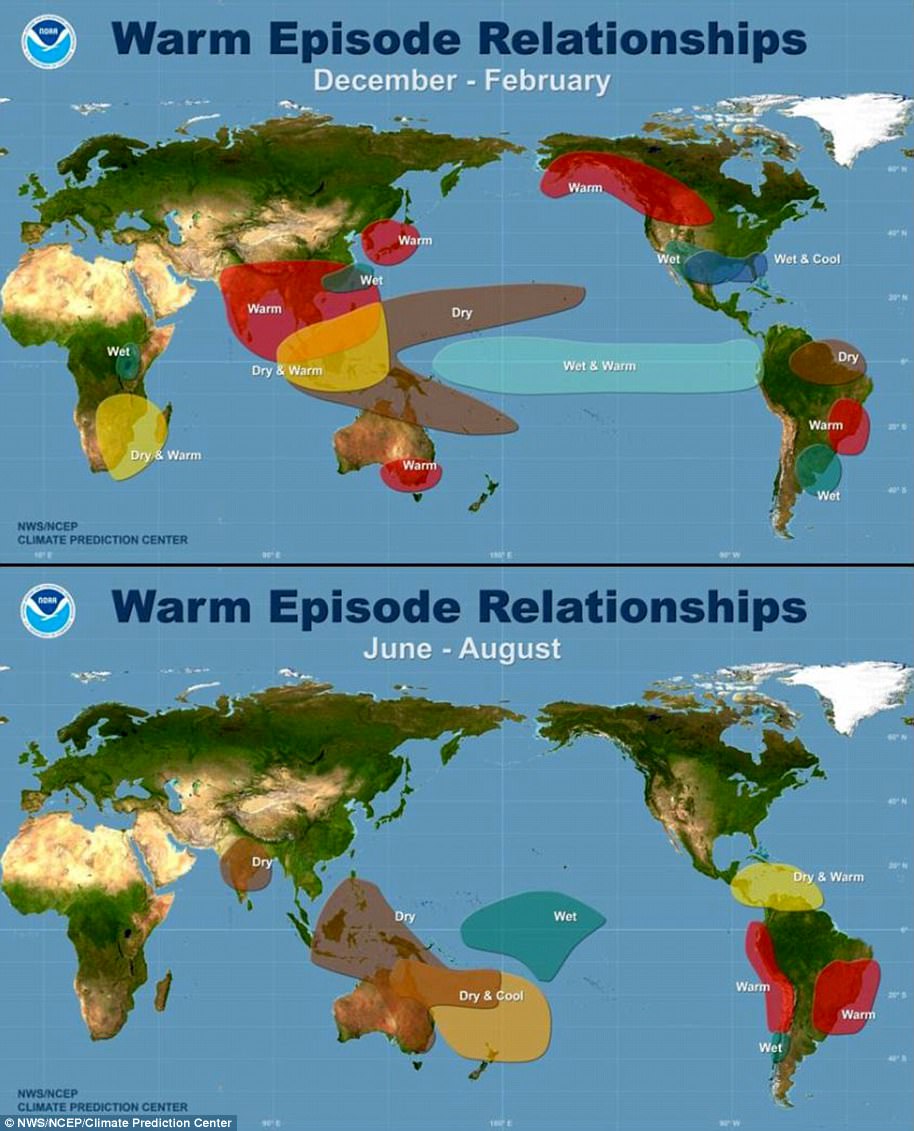

This is a concern as Atlantic La Niña events can have widespread impacts on nearby weather systems.

In A recent blog postNOAA scientist Dr. Franz Tuchen wrote: ‘Reduced rainfall in the Sahel region, increased rainfall in the Gulf of Guinea, and seasonal changes in the rainy season in northeastern South America have all been attributed to Atlantic El Niño events.’

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season is expected to be “extraordinary” as authorities have estimated there could be as many as 13 tropical cyclones. However, an Atlantic Niña could reduce the severity of the season

Exceptionally cold Atlantic temperatures in 2012 and 2013 led to devastating flooding in Brazil. Pictured: Flooded streets in Rio de Janeiro

In 2012, Brazil suffered severe droughts in the Northeast and floods in the Amazon region that coincided with unusually cold Atlantic waters.

In 2013, a phenomenon known as La Niña Atlantica was also followed by devastating floods in large areas of Brazil, including Rio de Janeiro.

Research published that year A study by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research concluded that the disruption of an Atlantic Niña was the likely cause.

On the more positive side, warm El Niño events in the Atlantic have been shown to increase the likelihood of powerful hurricanes forming near the Cape Verde Islands.

If this cooling event persists long enough to trigger a full-blown Atlantic La Niña, cooler waters could limit the increased hurricane activity expected this year.

Dr Tuchen says: “It will be interesting to monitor whether this Atlantic Niña fully develops and, if so, whether it has a dampening effect on hurricane activity as the season progresses.”