As Swifties devour her latest work, Taylor Swift is shedding some baggage via the Department of Tortured Poets.

After the Grammy winner, 34, released her 11th studio album on Thursday night, she decided instagram with a statement about how the launch signals the passage of a personal page.

‘The Department of Tortured Poets. “An anthology of new works reflecting events, opinions and feelings from a fleeting, fatalistic moment in time, one that was both sensational and painful in equal measure,” the caption began.

‘This period of the author’s life is now over, the chapter is closed and walled up. There is nothing to avenge, no scores to settle once the wounds have healed.

“And upon further reflection, a good number of them turned out to be self-inflicted,” Swift added.

After Taylor Swift released her 11th studio album on Thursday night, she took to Instagram with a statement about how The Tortured Poets Department marks the turning of her personal page.

She wrote that the album marks a “closed, walled-off chapter”, as Swifties speculate about some of the lyrics’ meanings.

‘This writer firmly believes that our tears become sacred in the form of ink on a page. Once we have told our saddest story, we can be free of it.’

Swift wrote: “And then all that remains is tortured poetry.” THE DEPARTMENT OF TORTURED POETS is now available.

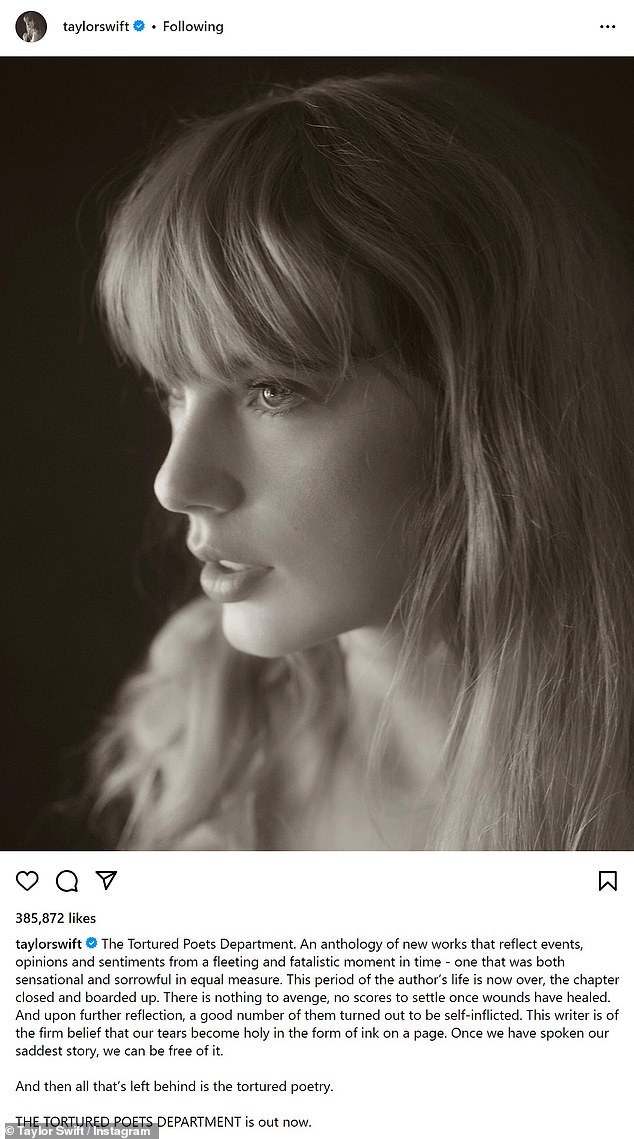

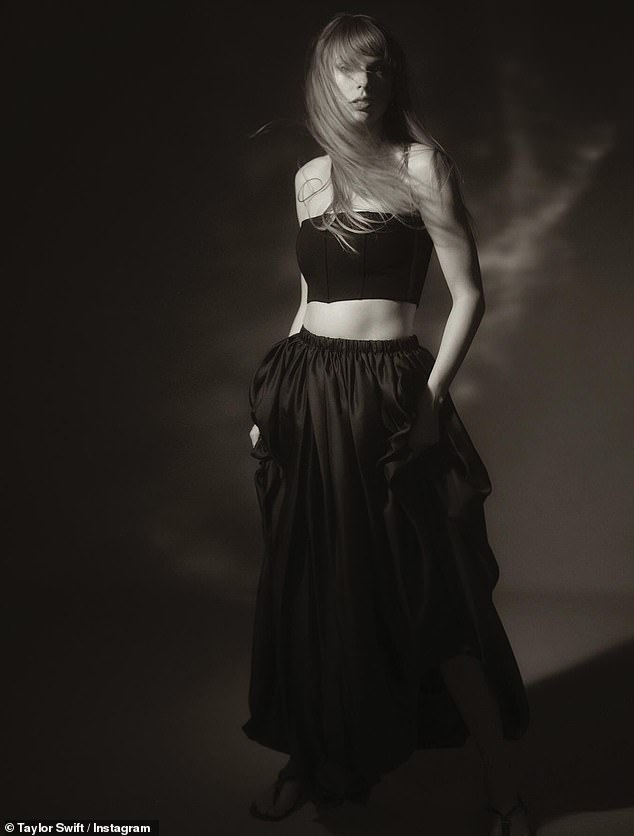

She shared the statement with some gorgeous black and white portraits from the album’s promotional shoot.

In anticipation of the album, Swifties have already sniffed out apparent nods to her boyfriend Travis Kelce in the lyrics, as well as her exes Joe Alwyn and Matty Healy.

Swift briefly dated Healy, 35, in 2023, following the end of her six-year relationship with Alwyn, 33.

Fans have speculated that the song title ‘So Long, London’ is a reference to the British actor, as well as the lyrics: ‘I wish I could forget how we almost had it all.’

The ‘Fortnight’ artist announced her latest album in February while accepting her lucky 13th Grammy Award, taking home Best Pop Album for Midnights.

After telling fans she would post the cover backstage, the image quickly racked up more than 2 million likes in five minutes.

She shared the statement with some gorgeous black and white portraits from the album’s promotional shoot.

In anticipation of the album, Swifties have already sniffed out apparent nods to her boyfriend Travis Kelce in the lyrics, as well as her exes Joe Alwyn and Matty Healy.

The ‘Fortnight’ artist announced her latest album in February while accepting her lucky 13th Grammy Award, taking home Best Pop Album for Midnights.

In March, Swift teased that it would be her most explicit album yet, with several tracks containing “profanity or language deemed to be sexual, violent or offensive in nature.”

Although the album reportedly leaked on social media earlier this week, TPD has broken Spotify’s record as the most pre-saved countdown page in the streaming platform’s history.

The release of TPD comes amid a two-month hiatus on Swift’s record-breaking Eras Tour, which resumes on May 9 in France.

The Department of Tortured Poets is now available for streaming and download.