The abdication of Edward VIII on December 11, 1936 was the culmination of a long standoff between the king, the Church and the government over Edward’s determination to marry the twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson.

Spiteful views on Edward’s private life finally burst onto the British public stage on December 3, 1936, and consumed the country for nine days, forcing a constitutional showdown that threatened the very fabric of national life.

Edward’s stubborn determination and his determined love for an unsuitable consort: these are the forces that have long been considered decisive in what became a defining moment of the 20th century British monarchy.

However, there is another equally influential but overlooked factor in how Edward arrived at his unprecedented decision: the fear bordering on paranoia that consumed Wallis in the final weeks of his reign.

A 1937 portrait of Wallis Simpson at the Kaiserhof Hotel in Berlin. She feared for her life when news of the King’s proposal finally broke and she fled London.

Wallis’s breaking point was a brick through the window of his house in Cumberland Terrace, next to Regent’s Park. This photograph was taken on December 3, 1936, the day her impending marriage to the King was made public.

The news of Mrs. Simpson’s friendship with the King was not well received by the public. Here, demonstrators protest against the impending abdication.

Now engaged, Edward and Mrs. Simpson are seen in Yugoslavia in 1936.

The first studio image of King Edward VIII and Mrs Wallis Warfield Simpson

Convinced that she was the target of the assassin’s bullet, the object of Edward’s all-consuming obsession fled England in a flurry of panic, leaving behind a lonely, sighing King, eager only to be reunited with the woman he loved.

It all started with a brick through a window…

On November 27, 1936, amid growing rumors about the relationship, and as Edward faced the question of marriage to Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, an unidentified man threw a brick through the house’s ground-floor window. of Wallis at 16 Cumberland Terrace.

In order not to miss his target, the attacker threw a second stone at Wallis’ neighbor, Lord Salisbury, just in case he had not found the correct address.

“A misguided bastard,” was how Max Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express, described the villain to Murphy. But maybe he’s a bastard with consequences.

In fact, the press baron came to believe that the broken windows had been “an even more influential factor than Baldwin in the king’s decision to abdicate without a fight.”

The episode certainly put Edward into overdrive. He interrupted his conversations with Baldwin at Buckingham Palace so he could personally escort Wallis to the safety of her home, Fort Belvedere in Windsor Great Park.

Wallis, Edward reflected, had found herself “outside the protection which at all times surrounds the person of the king”, and it became essential to him to extend around her the protective sphere of the royal orbit.

Until November 1936, the silent agreement between the monarch and the media had kept her name firmly out of the British press.

A portrait of Wallis Simpson from around 1936.

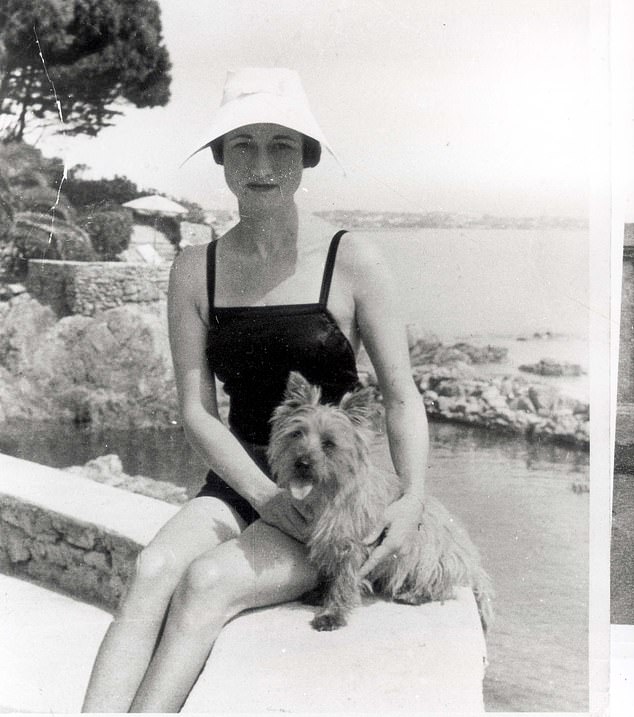

Wallis on holiday in the south of France in 1935 with her beloved dog and her slipper.

Mrs. Simpson obtained a divorce in 1936, the year of Edward’s accession to the throne. He made it clear to the British government that he was determined to marry her, whatever her obstacles.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor visit Government House in Nassau, Bahamas, in 1940

Unconcerned with public scrutiny, Edward had dazzled Wallis by transforming her comfortable middle-class existence with Ernest Simpson into one of unparalleled luxury.

Flaunting it with expensive jewelry and Parisian couture, Wallis became one of the fashion leaders of London society, a position she enjoyed.

‘Everyone succumbs to glamour; I dare anyone to say otherwise,’ she later reflected.

However, the explosion of hostilities, encapsulated in this single act of violence, shattered any illusions Wallis may have had about how the British public would react to her romance with Edward.

Her ‘physical shyness’, as Beaverbrook described it, came to light and fear overwhelmed her.

“That convinced her,” Beaverbrook continued, telling her husband’s ghostwriter, Charles JV Murphy, “that the British people were plotting to kill her. Her fears, in turn, awakened her courage. She rushed to protect her. And in doing so, she found herself siding with her against her own people.

However, even the protection of Fort Belvedere – a miniature fortress located in the shelter of Windsor Great Park – proved insufficient.

In less than a week, Wallis’s face, almost unknown in Britain, appeared in the headlines of the country’s newspapers. The anonymity she had enjoyed was destroyed and her world, as she later described it, “was blown up.”

Notoriety, at least for Wallis, translated into fear, and he became convinced that he was a target for assassination.

When she fled to France on the night of December 3, she left the country and a king who, as Beaverbrook emphasized, “had but one thought: to join her.”

On the way to Newhaven, where they were to catch the ferry to France, Wallis’s companion, Perry Brownlow, observed that she remained agitated, determined to escape, fearful of physical harm if she remained in Britain.

Her resolution proved disastrous, as deprived of any meaningful communication with Edward, she lost all influence. She was a witness rather than a participant in the final hours of the abdication crisis.

“I was fleeing for my life,” Wallis exclaimed to Murphy in March 1950 while describing the trip with Brownlow.

Dressed in a swimsuit, on her way to spend the day with glamorous American socialite Jayne Wrightsman, Wallis had appeared unexpectedly while Murphy and Edward were sitting together in “the white room overlooking the sea” at the financier’s palatial Palm Beach mansion. US. Young Robert.

Young was one of the Windsors’ closest friends in the United States and their frequent host.

Murphy had been helping Edward with the final revisions of his memoirs, scheduled to appear in the American photographic magazine Life, in May 1950, when Wallis burst in with a sudden, rebellious intervention: a complaint about the dangerous and traumatic circumstances of his escape. From great britain. and the population vengeful of it.

After hearing his wife’s dramatic pronouncement, the Duke of Windsor intervened, as Murphy noted, with “a slight objection”:

‘Honey, it wasn’t for your life. It was not so.’

The duchess, Murphy observed, “gazed him a stern look” and responded with unmistakable strength: “I was fleeing for my life.”

The disconnect between the couple was astonishing and convinced Murphy that the Windsors had “never discussed the circumstances of the abdication alone with thorough investigation.”

The front page of Beaverbrook’s Daily Express with a lead article on the abdication of King Edward VIII.

Edward VIII transmits his abdication to the nation and the Empire on December 11, 1936.

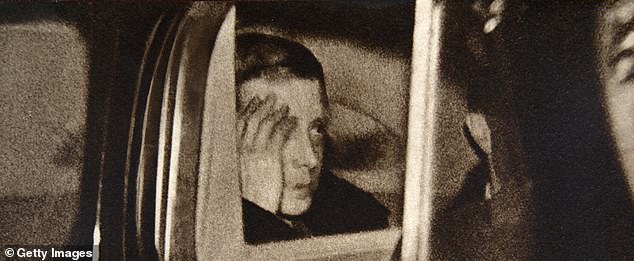

Edward VIII leaves Windsor Castle after his abdication speech

The moment showed Wallis at her fiercest and most determined, unafraid to contradict her most illustrious husband in what Murphy described as “the style of all self-assured wives” and fully demonstrated the qualities that Edward himself had identified in it: ‘independent… .demanding.’

However, in the final weeks of 1936 it was restlessness rather than fortitude that defined his actions and ultimately, as Murphy and others came to believe, the course of the king’s brief reign.

A brick thrown through a window ignited fear in a woman known for her steely determination.

And thus the calamity began.

- Jane Marguerite Tippett is the author of Once A King, the lost memoirs of Edward VIII published by Hodder & Stoughton, price £25