Suffering a sports-related concussion does not increase your risk of long-term brain damage, as long as you don’t play professionally, a new study suggests.

British researchers have found that head injuries while playing football or rugby not only did not increase the likelihood of cognitive decline in old age, but were even linked to a protective effect.

Contact sports have been marred by controversy over their links to dementia and other brain diseases in players, thought to be a result of frequent head impacts.

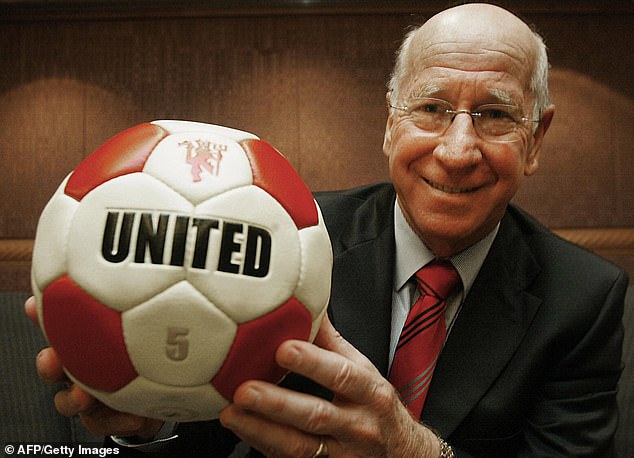

The most famous case is that of former English footballer Sir Bobby Charlton, who died at the age of 86 in 2023 after suffering from dementia.

Sir Bobby Charlton (pictured, holding a football with the word United written on it during an interview with local press at a Hong Kong hotel in 2005) died aged 86 from dementia in 2023.

Former England and West Bromwich Albion striker Jeff Astle has died aged 59 from an early-onset illness, apparently due to repeated head trauma.

Former rugby player Steve Thompson was also diagnosed with early-onset dementia at the age of 43.

A 2023 study commissioned by the Football Association and the Professional Footballers’ Association found that professional footballers are three times more likely to be diagnosed with dementia than the general population.

But the latest study suggests that amateur players may not fall victim to the same fate.

The study is the largest to date examining the long-term cognitive effects of sports-related concussions.

Researchers at the University of South Wales found that those who suffered a concussion while playing sports during their lifetime had slightly better cognitive performance than those who did not report having suffered concussions.

The study, published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, analyzed data from more than 15,000 participants in the UK Brain Aging Study of people aged between 50 and 90.

Researchers collected lifetime concussion histories from 15,214 participants using the Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire.

Among them, 6227 (39.5 percent) reported at least one concussion and 510 (3.2 percent) at least one moderate-severe concussion.

Former rugby player Steve Thompson was also diagnosed with early-onset dementia at the age of 43.

The former hooker revealed in 2022 that he no longer remembered winning the World Cup

On average, participants reported having suffered their last head injury an average of 29 years before the study and their first head injury an average of 39 years earlier.

Cognitive function was compared between those who had zero, one, two, or more than three concussions while playing sports and also between those who had zero, one, two, or more than three non-sports-related concussions.

The group that suffered sports-related concussions showed a 4.5 percent improvement in working memory, compared to those who did not have any concussions, and a 7.9 percent increase in reasoning ability.

People who suffered a sports-related concussion had better verbal reasoning and attention compared to those who did not suffer one.

But participants with more than three non-sports-related concussions, including accidents and assaults, had poorer processing speed and attention, and a declining trajectory of verbal reasoning with age.

A coroner ruled that Jeff Astle had died in 2002 from “industrial disease”, but former England and West Bromwich Albion striker Jeff Astle was said to have died aged 59 from repeated head trauma.

‘This study suggests that sport may have long-term benefits that could offset any negative effects of concussions, which could have important implications for policy decisions around participation in contact sports.

“It may also be that non-sport-related head injuries cause greater brain damage than sport-related concussions,” said lead author Professor Vanessa Raymont of the University of Oxford and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

He added that the study had some limitations, such as that older participants remembered details of events that occurred three decades ago, which may have affected their reporting of head injuries.

While most studies focus on the effects of concussion on younger athletes in the immediate period following their head injuries, this research reveals the effect on those in the middle and older years following concussions.

Dr Matt Lennon, MD, PhD, a researcher at the UNSW Medicine and Health Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA) and lead author of the study, says the results show that playing sports has long-term cognitive benefits.

He said: “While these results do not indicate the safety of any particular sport, they do indicate that sports in general may have greater beneficial effects on long-term cognitive health than the harm they cause, even in those who have suffered a concussion.”

“This finding should not be overstated: the beneficial effects were small and in people who had suffered two or more sport-related concussions there was no longer any benefit from the concussion,” he added.

But he stressed that this study does not apply to concussions in professional athletes, whose head injuries tend to be more frequent, debilitating and severe.

Anne Corbett, a professor at the University of Exeter and lead investigator of the PROTECT study, said: ‘What we see emerging is a completely different profile of brain health outcomes for people who sustain concussions as a result of sport compared to those who suffer concussions that are not sport-related.

‘Concussions that occur during sports do not cause brain health problems, while other types of concussions do, especially when people experience multiple concussions.

‘In fact, people who play sports appear to have better brain health regardless of whether they have suffered a concussion while playing sports or not.’