Sean Garinger’s ex Selena Gutierrez has broken her silence in the wake of his tragic and untimely death, revealing that she was 200 days sober and had been “very happy” spending time with her two young daughters just a week earlier.

Sean, 20, who appeared on MTV’s 16 and Pregnant, died last Wednesday when an all-terrain vehicle he had attempted to move in front of his home in Boone, North Carolina, overturned and landed on top of him.

Speaking to DailyMail.com for the first time since the tragic accident, Selena, also 20, described Sean as her “first love, my first everything” as she lamented how to break the news to her daughters. Dareli, three, and Esmi, 19 months.

“Sean and I weren’t on the best of terms, but we had finally moved on with our lives,” she said. ‘We never really spoke one on one, it was always through my sisters or his mother and he was better. He was more than 200 days sober. He had just come to visit the girls a week before.

Sean Garinger had been sober for 200 days and was ‘very happy’ to see his daughters Dareli, three years old, and Esmi, 19 months, just a week before he died.

Sean and Selena, both 20, appeared on the sixth season of 16 and Pregnant, which documented their journey as new parents.

‘I know from what his mother said that he was happier than ever to see them. The girls loved him. She was planning to come back and see them on her own.

‘I know he was at school. She left rehab and moved with her mother to Carolina. My heart aches for her.’

He added: “I wish we had had another good conversation about everything.”

The former reality star recalled how she was getting ready in her room in Fountain, Colorado, when her sister walked in to give her the devastating news last week, leaving her in shock.

Selena said: “She just looked at me and said, ‘Sean’s gone.’ I was like ‘what do you mean?’ She said, ‘Sean’s dead.’

“I remember being shocked and saying, ‘No way, you’re lying.’ She said, ‘No, (Sean’s mom) just called me.’

Sean and Selena appeared on the sixth season of 16 and Pregnant, which documented their journey to becoming parents for the first time in 2020.

Their struggles also appeared on the reality show, with Selena accusing Sean of cheating on her while she was pregnant.

Selena is struggling with how she will break the devastating news to her daughters in the future.

Selena’s older sister Thalia, 25, also paid tribute to Sean and said her “heart will forever break” for her nieces.

Sean was killed when an all-terrain vehicle he was planning to move rolled over on top of him.

They also got into a fight and Selena was allegedly arrested.

But despite their tumultuous time together, the mother-of-two said she had been “crushed” by the news and was struggling with how to tell her young daughters.

“No matter the circumstances, that was the father of my children,” she said. ‘Not only was I with him for over nine years, but he was my first love, my first everything and we had two beautiful daughters for whom I will always be grateful.

‘They didn’t deserve this, they need their dad. I don’t know how I’m going to tell them when they’re older.’

Selena’s older sister Thalia, 25, also paid tribute to Sean, saying her “heart will forever break” for her nieces, who will only know their father through “photos and videos.”

“Sean’s loss was very sudden and tragic,” she told DailyMail.com. ‘The last few months of his life he was trying to get better for my nieces. It’s really sad to see his life cut short.

‘We all had a different relationship with Sean. As for me, we were close until there were family conflicts and then the last time I saw him it was like everything was back to “normal” – he was goofy and definitely knew how to push your buttons, but that was his way of showing love. .’

She continued: ‘My deepest condolences to his family, especially his mother. As for my nieces, my heart will forever break for them. They never really had the opportunity to meet her father. The only thing that remains are photographs and videos of him.

Sean’s mother, Mary Hobbs, 40, witnessed the accident which “crushed” his skull. She ‘lay down next to’ him on the ground before rescuers arrived.

“I ran to the neighbors trying to get someone to help me get the ATV off of him,” he told the US Sun. ‘Nobody answered. I ran towards him. At that moment I realized that he was no longer alive.

‘There was a big part of my heart that died with my son on Wednesday. He was my only son, my rock, my strength when I had none left.’

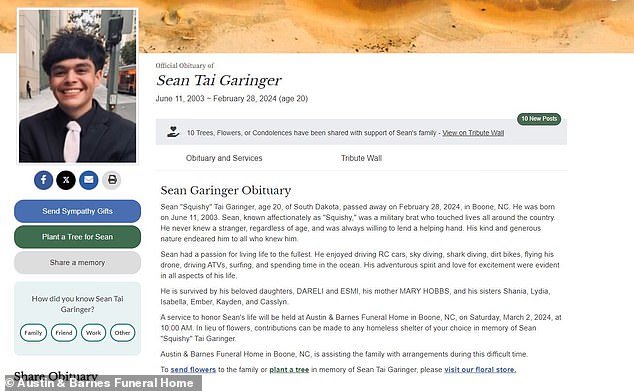

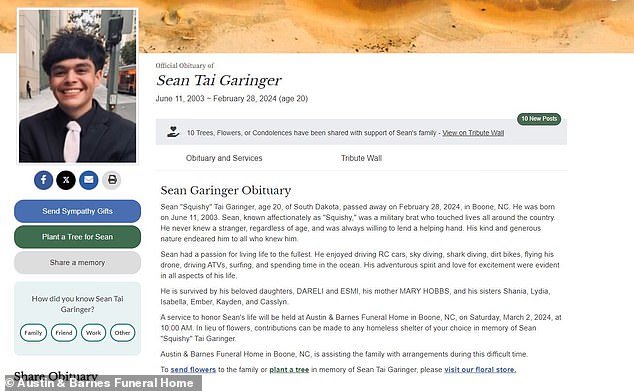

According to an obituary published by Austin & Barnes Funeral Home, Sean was affectionately known as ‘Squishy.’

Maj. Kelly Redmon of the Watauga County Sheriff’s Office told the Watauga Democrat on March 1 that Watauga Medics and the Watauga County Sheriff’s Office had responded to the fatal crash, identifying Sean as the victim.

“Our hearts are heavy with pain at the loss experienced by the victim’s family and loved ones,” WCSO said in a news release.

According to an obituary published by Austin and Barnes Funeral HomeSean was “affectionately known as “Squishy”” and was a “military brat who impacted lives across the country.”

It said: “He never met a stranger, no matter their age, and was always willing to lend a hand.” His kind and generous nature endeared him to all who knew him.

The obituary noted that Sean “had a passion for living life to the fullest” and said that “his adventurous spirit and love of excitement were evident in all aspects of his life.”

“He enjoyed driving RC cars, skydiving, shark diving, dirt bikes, flying his drone, driving ATVs, surfing, and spending time in the ocean.”

A memorial service was held Saturday at Austin & Barnes Funeral Home.