Many of us harbor vain fantasies about creating a multimillion-dollar business from scratch, living in a mansion, and flying to work by helicopter. Richard Harpin was there, he did that and now he wants to share his formula with other aspiring tycoons.

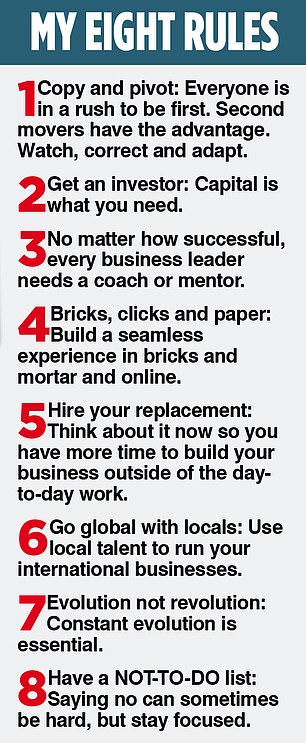

He’s telling the world his eight secrets to creating a billion-pound business.

The secrets, which include finding a mentor and making sure to hire a replacement, might at first seem more like common sense than a spectacular, eye-opening plan. But that’s easier said than done and he believes he would have done even better as an entrepreneur if he had discovered these nuggets sooner.

He set up his company HomeServe, selling home disaster insurance policies, in 1993 and sold it 30 years later for £4bn, making himself £500m from the deal.

‘My secrets are the eight things that, looking back over 30 years ago, I know now and wish I knew then. If he had, he could have grown HomeServe in half the time. Which of the eight is the most powerful secret depends on where the company is in its journey.”

Success: Richard Harpin set up his company HomeServe, which sells home disaster insurance policies, in 1993 and sold it 30 years later for £4bn.

One of the most important, at any time, he says, is to have a “don’t do” list.

“My mistakes are largely due to the fact that I am a typical businessman who tries to make too many ideas a reality,” he says. ‘Every company should have a hedgehog strategy. If someone comes with crazy ideas, get nervous and tell them to get lost because they need to stay focused.’

Among its secrets is also finding good investors and not being ashamed of copying good ideas if you can do them better.

“There are a lot of more complicated business theories,” says Harpin, but adds: “I’m a Yorkshireman and I hope to keep my feet on the ground.”

His latest idea is ‘coaching’, a concept that he has as a registered trademark and which is a mix of coaching and mentoring. The word (dare I say it) sounds a bit pretentious for Yorkshire, but he is the billionaire, not me.

“If I had known the eight secrets at the beginning of my career, I could have achieved success with HomeServe in 15 years instead of 30.”

‘As a country, if we convert more medium-sized businesses into large ones, we wouldn’t have to worry about government help to boost the economy. They would be entrepreneurs who would take success into their own hands.’

Harpin, 59, is putting his money where his mouth is, betting £165m of his personal fortune on younger entrepreneurs who he believes can build multi-billion pound businesses.

Companies it has supported so far include outdoor clothing retailers Passenger and Acai, luggage brand Stubble & Co and hair extension company Added Longitudes.

By now, budding billionaires will no doubt be wondering if Harpin could also become their Fairy Godfather.

Instead of setting up Dragons’ Den-style auditions, he searches for companies by turning to two researchers who have compiled a list of 11,000 medium-sized companies.

‘They check them at a rate of about 100 a week. I put in between £5m and £15m per company.

He prefers to support retail companies that already make “a couple of million pounds” of profits.

Another of his eight secrets is what he calls “bricks, clicks and paper”, meaning that retail businesses must cover all sales channels: the high street, online and catalogs and directories.

Checkatrade, which helps homeowners find traders, finds the mini-directories it sends through mailboxes to be surprisingly successful.

He says he hasn’t checked his earnings yet, but he made £5 million from an initial stake of £750,000 in his only sale so far, from Enterprise Nation, a community of small businesses and advisors aiming to shorten the path to support .

Harpin says he has “killer questions” that he uses when hiring or investing, so it seems fair to turn the tables. When I ask him to describe a moment of adversity from his childhood, he dives straight into Lord of the Flies territory.

Hooked: As a schoolboy, Richard Harpin built a business selling fly fishing lures, which proved popular as earrings.

‘At Scout camp, some kids watched me with wooden stakes in an anthill, because my mother was the Cub Scout leader. I was there for about an hour and the ants were biting me. I was about 12 years old at the time. Today it would be seen as bullying, but it made me more determined.”

The episode did not deter him from the Scouts. He is a big supporter and introduced an entrepreneur badge in 2010, which is still in place.

Harpin himself started businesses when he was still wearing shorts. The first was to sell fly fishing lures, which look like insects and are tied to a hook as bait. He found a market in women who wore them as earrings.

“I knew I was an entrepreneur from the age of four,” he says. He continued his fly fishing adventure until he graduated, earning enough to put down a deposit on his first house.

At the age of nine he began raising white rabbits for conjurers and became a boy magician at the age of 11.

Born in Huddersfield and raised in Northumberland, Harpin describes himself as “a northerner through and through”. After graduating in economics at York, he began working in marketing at Procter & Gamble, the American consumer goods giant, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

“My first job was a marketing assistant at Fairy Liquid, that’s why my hands are so soft,” she jokes. His contemporaries included BT’s new boss, Allison Kirkby, and two of his predecessors, Philip Jansen and Gavin Patterson.

When I first met Harpin in 2008, he was traveling by helicopter between his home in Yorkshire and his workplace at HomeServe in Walsall, in the West Midlands. He would get up at five in the morning, go swimming outdoors at his gym in Lichfield, Staffordshire, and fly home so he could swim again with his young children.

A major Conservative donor, he lent one of his helicopters to Rishi Sunak to fly to engagements, sparking controversy over why the Prime Minister didn’t take the train.

On the cusp of his seventh decade he still lives at a dizzying pace.

“I don’t want to retire to a desert island, I want to work forever,” he says. She is developing career goals “for the next 30 years.”

His new role model, he says, is Malcolm Healey, a fellow Yorkshireman and founder of Wren Kitchens. Harpin says: ‘He is 79 years old and still works full time. Wren Kitchens is his fourth business.

Far from being an overnight triumph, HomeServe struggled in its early days. Several ideas didn’t work until he came up with one that did: plumbing insurance for South Staffordshire Water. By the mid-2000s, HomeServe was eclipsing its parent company and was listed on the stock market at a valuation of £300m.

There have been serious setbacks, including a £30m fine a decade ago for mis-selling policies and failing to investigate complaints properly. At the time, a remorseful Harpin apologized and said he had “transformed” the company.

“The best time to start a business (and grow it) is during difficult economic conditions,” he says. “Because if you can do that, then think about what will happen when we get back to higher levels of growth.”

But he adds: ‘More attention should be paid to the financing of medium-sized companies. I can only contribute £165 million of my money.

“I can’t do it all alone.”

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.