…when I ask my mother if she remembers, her answer is the same: ‘Vaguely.’

And I believe him. Because much of my early childhood is vague. Some things, however, I remember with absolute clarity. At seven I knew something was wrong. I didn’t care about things like other kids. Certain emotions, such as happiness and anger, emerged naturally, if somewhat sporadically.

But social emotions (things like guilt, empathy, remorse, and even love) did not. Most of the time I didn’t feel anything. So I did “bad” things to make the nothingness go away. It was like a compulsion.

If you had asked me back then, I would have described this compulsion as a pressure, a kind of tension that was building up in my head. It was as if the mercury was slowly rising in an old-fashioned thermometer.

It was barely noticeable at first, just a blip on my otherwise peaceful cognitive radar. But over time it would grow stronger. The quickest way to relieve the pressure was to do something undeniably wrong, something I knew would make anyone else feel one of the emotions I couldn’t feel. So that’s what I did.

As a child, I didn’t realize there were other options. I didn’t know anything about emotions or psychology. She didn’t understand that the human brain has evolved to function with empathy, or that the stress of living without natural access to feelings is believed to be one of the causes of compulsive acts of violence and destructive behavior.

Gagne was eight years old at the time of the stabbing.

All I knew was that I liked doing things that made me feel something, feel anything. It was better than nothing.

He was carrying school backpacks. She didn’t even want them and almost always gave them back in the end. When I saw an unattended backpack, I grabbed it. It didn’t matter where she was or whose she was, what mattered was the shot. Doing anything I knew wasn’t “right” was how I released the pressure, how I gave myself a jolt to counteract my apathy.

However, after a while it stopped working. No matter how many bags he carried, he could no longer generate that shake. I did not feel anything. And I began to notice that nothingness made my need to do bad things more extreme.

This was my mood the last time I saw Syd, one of my classmates. We were on the sidewalk waiting to go to school when she started complaining about visiting my house.

She wanted to spend the night but her parents refused and she blamed me. I was glad she wasn’t allowed to visit me. My head hurt. The pressure had been steadily increasing, but nothing I did seemed to help. She was emotionally disconnected but also stressed and somewhat disoriented.

It was like I was losing my mind and just wanted to be alone.

Suddenly, Syd kicked my backpack from where it was at my feet, knocking everything to the ground. ‘Did you know?’ she said. ‘I don’t mind. Your house stinks, and so do you.

The tantrum was pointless, something she had done to get my attention like countless times before. But she had chosen the wrong day to start a fight. Looking at Syd I knew I never wanted to see her again.

Without saying a word, I bent down to pick up my things. Back then we carried pencil boxes. Mine was pink with Hello Kitty characters and filled with sharp yellow number 2s. I grabbed one, stood up, and stuck it in the side of his head. The pencil splintered and some of it lodged in his neck. Syd started screaming and the other kids understandably lost control.

Meanwhile, he was stunned. The pressure disappeared. But unlike all the other times I’d done something bad, my physical attack on Syd had resulted in something different: a kind of euphoria.

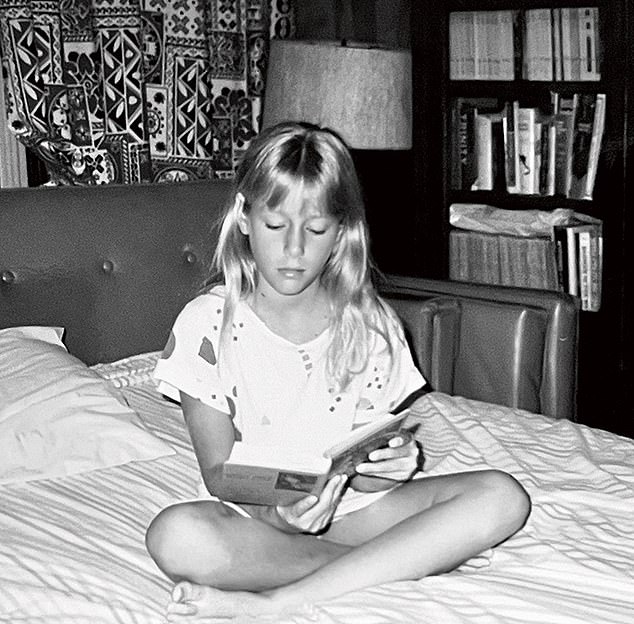

Patric Gagne sits down with Julia Llewellyn Smith in an exclusive interview with YOU Magazine this weekend

I walked away from the scene happily at ease. For weeks he had been engaging in all sorts of subversive behavior to get the pressure off and none of it had worked. But now – with that violent act – all traces of pressure were eradicated. Not only did it disappear but it was replaced by a deep sense of peace. It was as if he had discovered a quick route to tranquility, a route that was equal parts efficiency and madness.

None of it made sense, but I didn’t care.

I wandered around in a stupor for a while. Then I went home and calmly told my mother what had happened.

‘WHAT THE HELL IS GOING ON IN YOUR MIND?’ my father wanted to know. That night she was sitting at the foot of my bed. My parents stood in front of me, demanding answers. But I didn’t have any.

“Nothing,” I said. ‘I don’t know.

I just did it.’

—And you don’t feel it? Dad was frustrated and irritable. He had just returned from another work trip and they had been fighting.

‘Yeah! I said I was sorry!’ I exclaimed. She had even already written Syd a letter of apology. So why was everyone still so angry?

I hated the way my mother looked at me that night.

“But you don’t regret it,” Mom. he said silently. ‘Not precisely. Not in your heart. Then she looked at me like I was a stranger. paralyzed me, that look. It was a look of confused recognition, as if to say, “There’s something strange about you.” I can’t put my finger on it, but I can feel it.

My stomach flipped as if I had been punched. I hated the way my mother looked at me that night. She had never done it before and she wanted it to stop. Seeing her look at me like that was like being watched by someone who didn’t know me at all. Suddenly, I was angry with myself for telling the truth. He hadn’t helped anyone “understand.”

If anything, it had confused everyone even more, including me. Eager to make things right, I stood up and tried to hug her, but she raised her hand to stop me.

“No,” she said. ‘No.’ She looked at me long and hard one more time and then left. I watched as Dad followed her out of my room, her body getting smaller as they descended the stairs.

I got into bed and wished I had someone I could hurt, so I could feel the way I felt after stabbing Syd. Getting ready, I clutched a pillow to my chest and dug my nails into my forearm.

‘Feel it!’ I hissed. I continued to claw at my skin and clench my jaw, wanting remorse with all my might.

I don’t remember how long I tried, just that I was desperate and furious when I finally gave up. Exhausted, I collapsed back into bed. I looked at my arm. I was bleeding.

The euphoria I felt after stabbing Syd was both disconcerting and tantalizing. I wanted to experience it again. I wanted to suffer again. Only I didn’t want to. She was confused and scared. He wasn’t sure how things had gone so wrong. I just knew it was all my fault and I had to find a way to make it better.

Taken from Sociopath: a memoir by Patric Gagne PhD, to be published by Bluebird on 11 April, £18.99. To pre-order a copy for £16.14 until April 21, visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £25.