Mike Lynch’s first computer breakthrough was a program that allowed law enforcement to instantly match suspects’ fingerprints to records in their database.

In the early 1990s, it would have been hard to believe that the tech genius hailed as Britain’s answer to Bill Gates, who would later become an advisor to David Cameron’s government and also sit on the BBC board, would one day his own fingerprints taken.

But, in a titanic fall from grace that has seen the 58-year-old tycoon spend much of the past year under house arrest with an electronic tag attached to his ankle, Lynch will enter a San Francisco courtroom today to defend against fraud. and conspiracy charges that could see him imprisoned for decades.

To defend its positions is a legal team led by Reid Weingarten, one of the most renowned white-collar defenders in the American justice system, whose client list includes such famous figures as director Roman Polanski, who fled the States -United in the late 1970s after admitting to the statutory rape of a minor, and the late serial pedophile and friend of Prince Andrew, Jeffrey Epstein.

A master at portraying the rich and famous, Weingarten said he sometimes feels like he’s in the French Revolution, “defending the nobility against the screaming mob.”

Mike Lynch on his Suffolk farm as he fights extradition

A string of high-profile Silicon Valley entrepreneurs – from Elizabeth Holmes of blood-testing company Theranos to cryptocurrency “guru” Sam Bankman-Fried – have been exposed in recent years as brazen frauds.

Infected by the tech industry’s mantra of “fake it till you make it,” they ended up in prison after being caught wildly exaggerating their business achievements.

Mike Lynch OBE has also been hailed for having the Midas touch, and the Essex bluffer, a 007 obsessive who rather resembles a Bond villain himself, has become a leading figure in a British tech industry that has produced few truly global figures.

He now faces up to 25 years in prison in the United States if convicted on 17 counts of conspiracy and securities and wire fraud.

The accusations relate to the business deal that was hailed at the time as his crowning achievement: the £8.6 billion sale of his software and data company Autonomy to US IT giant Hewlett-Packard (HP) in 2011.

Lynch, who personally made more than £500 million from the deal, became one of the richest people in Britain and everyone wanted to hear his advice on how to get ahead in business.

But the shine quickly faded when HP wrote down three-quarters of Autonomy’s value just a year after buying it, firing Lynch and accusing him and other executives of grossly inflating its size and profits upon sale.

Lynch, as well as Autonomy’s former vice president of finance, Stephen Chamberlain, deny the accusations but will have an uphill task proving their innocence in the face of formidable U.S. federal prosecutors, who rarely lose such cases.

It doesn’t help that Lynch already lost a civil fraud case in 2019 based on similar allegations that HP – now Hewlett Packard Enterprises (HPE) – had made in the UK. The High Court ruled in 2020 that HPE had “substantially won” its case.

His separate three-year fight to avoid extradition and face criminal charges culminated in Lynch going to the high court to argue that U.S. prosecutors were guilty of legal abuses that threatened sovereignty of the United Kingdom and its citizens.

His plea was rejected, and last May he was flown to California, accompanied by the US Marshals Service, who continue to loudly protest his innocence.

The trial that begins today will take place before a jury in a city just 30 miles from HPE’s headquarters in Silicon Valley.

At least the trial will get him out of the house. After prosecutors convinced a judge that Lynch posed a serious flight risk, he was forced to post $100 million (£78 million) bail, surrender his passport and agree to subpoena at residence.

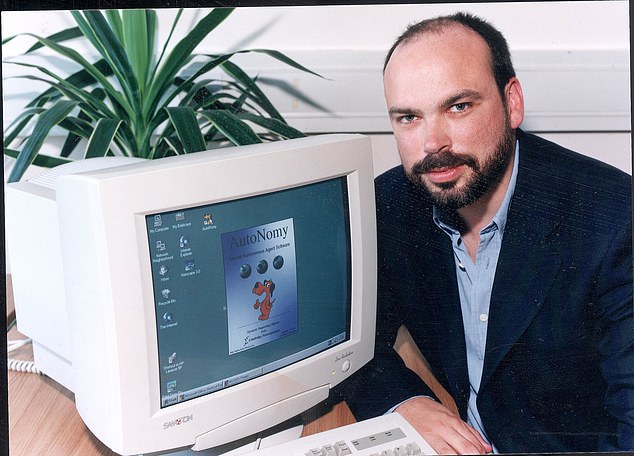

Mike completed a PhD in mathematical computing and started his first business in the late 1980s with just £2,000.

As a result, for the past 11 months, Lynch has been largely confined to a £27,000-a-month rented house in posh Pacific Heights, with video cameras scanning every room 24 hours a day and this GPS tracking bracelet at the ankle. .

The judge overseeing his trial recently relaxed his conditions of detention slightly, allowing him to go outside between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m., but only if he is escorted by two armed private security guards – a service he had to pay for himself.

Described by the security firm that monitors him as a “supermodel,” Lynch is said to have spent his days talking to his investment firm, Invoke Capital, checking on the research he funds at Cambridge into artificial intelligence and get updates on the health of his rare breed. Red Poll cattle on his farm in Suffolk.

And, more urgently, he is discussing with his lawyers how he intends to defend himself during a trial that could extend until the end of May. In this case, they will have their work cut out for them.

HPE revealed last month that it was seeking more than £3 billion in damages from Lynch, estimated to be worth £1 billion, although its lawyers put the figure at £350 million at maximum.

However, retaining his freedom rather than his wealth will be the priority in the coming weeks for a man who prosecutors reportedly plan – with the help of testimony from former employees – to portray as an authoritarian and ruthless tycoon who behaved in business as an iron-fisted mafia boss.

And Lynch, a Cambridge-educated computer expert who liked to pepper his public statements with criminal talk – “In technology, you have to bring a gun to a knife fight,” was one of his optimistic lines – is not certainly nothing, if not unconventional.

He continued to bring up the far-fetched connection to crime in his corporate videos. In a five-minute film aimed at Autonomy’s sales staff and made in 2005, Lynch poses as a mob boss known as “Big Mike” taking a conference call with his underbosses, all wearing mafia style fedoras.

As Big Mike sits at his desk sharpening his knife, one of his servants complains that he couldn’t put a “rival’s wife in the trunk of the car” because “the legs of the sea were too long.

Another jokes about having to tie someone up with string “but he kept escaping”, while a third is so angry at workers’ inability to “collect” that he smashes a phone with a baseball bat.

Some might view the video as harmless entertainment, but U.S. prosecutors say it was actually very revealing. They plan to present the video at Lynch’s trial as evidence of his thuggish management style.

They plan to call witnesses who will say that he often compared Autonomy to the mafia and presented himself as someone “to whom the rules do not apply.” He allegedly told an employee: “You can never leave, we’re like the mafia, we’re like family.” »

Prosecutors accuse Lynch of not only “artificially inflating” Autonomy’s balance sheets and falsifying its accounts, but also of intimidating or firing analysts who challenged them.

According to prosecutors, Lynch once told his investor relations manager that he might have a research analyst “killed” for criticizing the company.

During pretrial hearings, Lynch’s attorneys objected to the prosecution’s inclusion of the corporate video as evidence, saying it was a “harmless joke.”

They accused prosecutors, who also want to point out to jurors their client’s fondness for Bond villains, of engaging in a desperate smear. “HP was not defrauded and got exactly what it bargained for,” its lawyers say.

They claim that HP’s case is just a “case study in buyer’s remorse” and that the American company – which paid 66 percent more than its market value for the Autonomy – knew exactly what she was getting.

Desperate to expand its business beyond building computers and printers, Hewlett-Packard ruined the software company through its own mismanagement, Lynch’s team claims.

Raised in Chelmsford, Essex, by working-class Irish parents – his father was a firefighter, his mother a nurse – Lynch won a scholarship to a private school in east London, then a place at University from Cambridge, where he studied mathematics, physics and biochemistry.

He later earned a doctorate in mathematical computer science. He started his first business in the late 1980s with just £2,000.

In 1991, he created Cambridge Neurodynamics, which specialized in computer fingerprint recognition, and co-founded Autonomy Corporation five years later.

The latter quickly became an emblematic figure of Silicon Fen, the nickname given to the group of technology companies around Cambridge which was Britain’s answer to Silicon Valley.

In 2010, the company was so successful that Lynch signed a £20 million shirt sponsorship deal with Tottenham Hotspur.

As his star grew with him, Lynch was embraced by the British establishment.

In 2006 he received an OBE for services to business and was appointed to the BBC board the following year. He also became a trustee of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, a Fellow of the Royal Society and Deputy Lieutenant of Suffolk. In 2011 he was appointed to the Science and Technology Council by the then Prime Minister David Cameron.

Unfortunately for Mike Lynch, such tinsel may not count for much as American jurors are asked to determine whether he ripped off one of their country’s most famous tech companies.