The great Don Bradman’s view that rebellious Australian cricketers were right to accept huge amounts of money to play in South Africa during apartheid has been revealed in a series of letters that also set out the sadness the sporting icon felt in the last years of his life.

More than 20 letters The Don wrote to a friend in England between 1984 and 1998 have been unearthed from the National Library of Australia.

The correspondence offers valuable insight into what the Australian thought about a range of the biggest issues facing the game, including the fact that he thought it was hypocritical for Australia to condemn stars for touring a racially divided South Africa at a time when The federal government traded freely. with the country.

One of the main issues that affected cricket was apartheid in South Africa, about which Bradman had very strong opinions.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination implemented in South Africa between 1948 and 1994.

It imposed strict racial divisions, denying basic rights and freedoms to the majority of the black population and privileging the white minority.

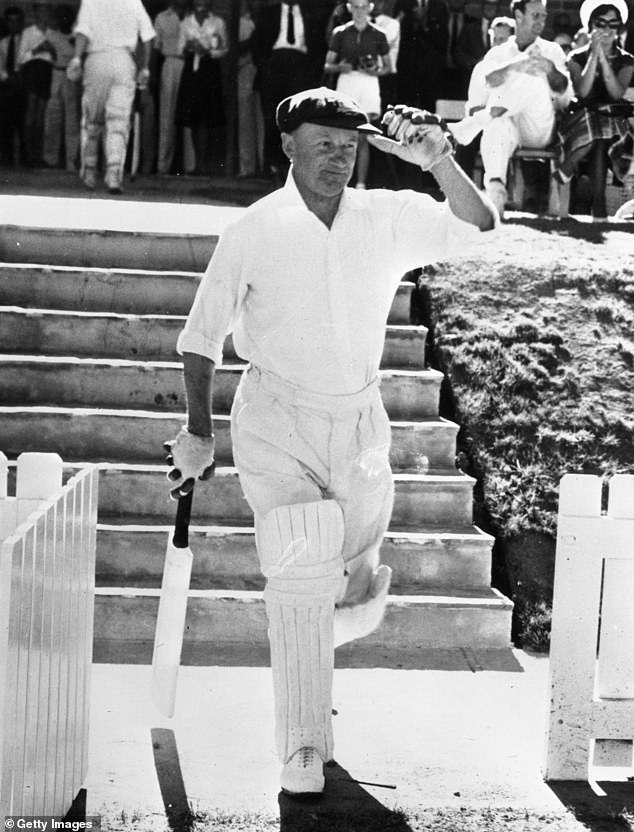

The great Donald Bradman believed that Australian cricketers were right to accept huge amounts of money for rebel tours to South Africa.

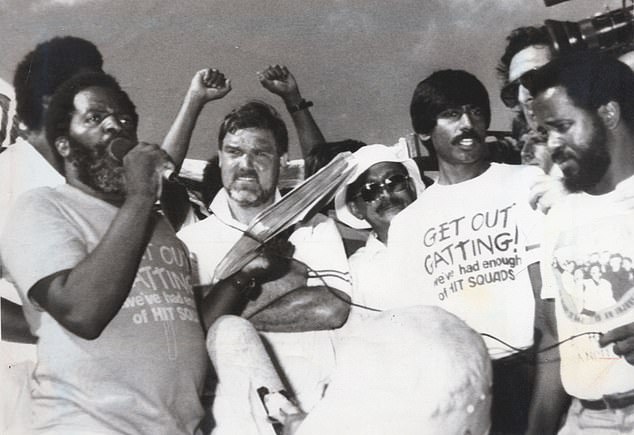

Rebel trips to South Africa were met with intense opposition, as former England captain Mike Gatting (centre) discovered during this protest in 1989.

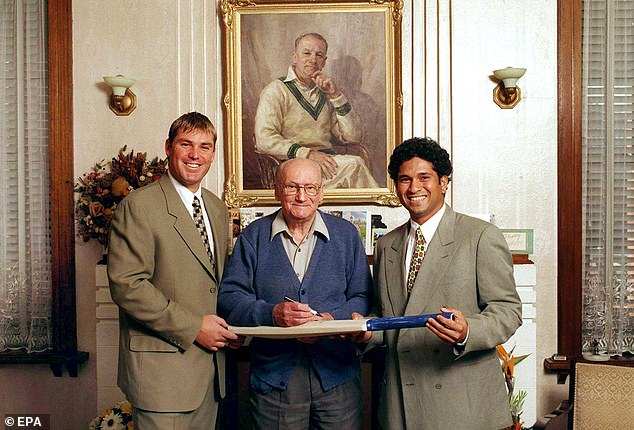

Bradman, pictured with Shane Warne and Sachin Tendulkar, canceled an Australian tour of South Africa when he was president of the Australian Cricket Board in 1970.

This oppressive regime ended thanks to internal resistance and international pressure, leading to democratic elections and the leadership of Nelson Mandela in 1994.

Apartheid led to South Africa’s exclusion from international sports, including a ban from the International Cricket Council in 1970, and South Africa did not rejoin international cricket until 1991, after the system began to be dismantled.

Many nations refused to compete with South Africa and rebel tours by foreign players who defied the boycott faced global criticism.

Bradman was involved in efforts to boycott South Africa during the 1960s and 1970s in response to the country’s apartheid policy:

As president of the Australian Cricket Board, Bradman canceled the 1970-1971 South African cricket tour of Australia.

He also declared that there would be no more cricket tours of South Africa until its teams were chosen on a non-racial basis.

However, stars Kim Hughes, Terry Jenner and Graham Yallop were part of a team of 14 prominent Australian players who joined these unofficial tours in the 1980s anyway, attracted by significant financial incentives.

Bradman’s views on apartheid and rebel tours have been revealed in a series of letters he wrote to a friend in England.

These tours were widely condemned, with participants facing bans from official cricket and criticism for undermining the global anti-apartheid stance.

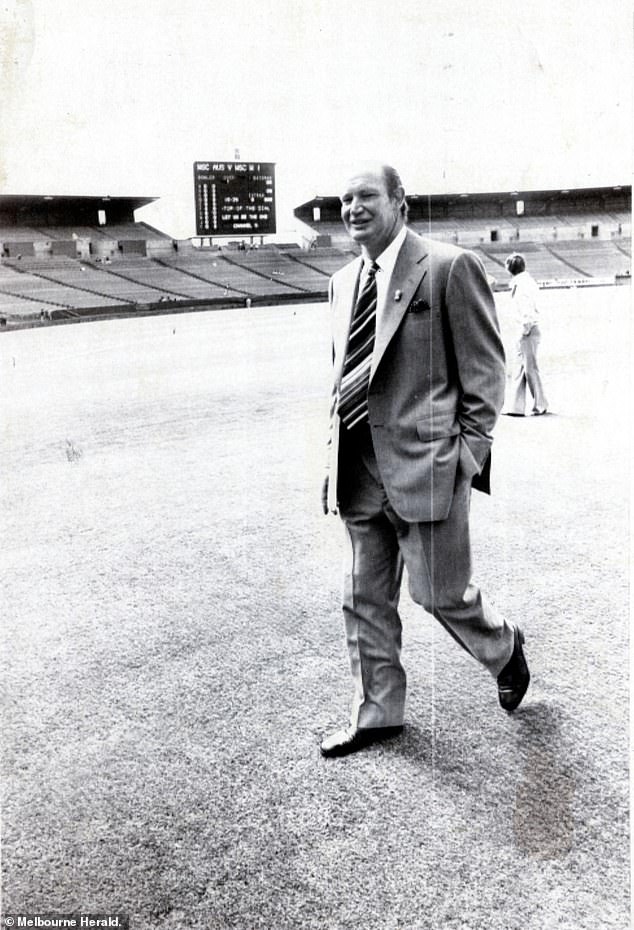

The timing also clashed with World Series Cricket, Kerry Packer’s brainchild in 1977 that would pave the way for ODI cricket by introducing night matches, colored uniforms and better salaries for players.

Bradman wrote that he feared that the rebel tours would lead to another separatist competition led by the Packers, and feared that the “black” countries would never lead South Africa back into world competition.

“Since I last wrote, the cricket world has been abuzz,” he wrote.

‘With players signing for England and South Africa and Packer signing players separately, God knows where it will all end.

“I don’t blame the players. One I know has been out of work for two years and seeing a $200,000 joust (sic) for two years was too good to turn down.

Of course, all this depends on dirty and rotten politics.

‘Our government trades freely with South Africa and it is total hypocrisy for them to prevent sporting contacts.

“The ‘black’ countries will never agree to readmit South Africa and the final answer is a total division between blacks and whites.”

However, Kerry Packer’s breakaway contest never occurred and South Africa was eventually readmitted to world cricket, but as a result of economic policy, not due to a seismic action of the sport.

Nelson Mandela would later describe Bradman as his “greatest hero” for his stance against apartheid.

Bradman feared apartheid would destroy the cricket world, and had the same fears about the one-day revolution started by Kerry Packer (pictured).

Nelson Mandela was a great admirer of Bradman for his stance against the horrible racial discrimination in South Africa.

‘Mandela loved Bradman for the stance he took on racism. Perhaps more than anyone,” wrote Bradman’s biographer and close friend Roland Perry.

Unfortunately, due to Bradman’s frailties in his final year, he never got to meet Mandela.

Sadly, Bradman also wrote in his letters about his loneliness in his final years before he died in 2001.

Bradman’s wife, Jessie Menzies, died in 1997, while many of his teammates also predeceased him.

Vice-captain Lindsay Hassett died in 1993, Sid Barnes tragically took his own life aged just 57 in 1973 and fast bowler Ray Lindwall died in 1996.

‘I’m struggling to move on with life, but everywhere I go there is sadness and memories. Even after a game of golf or bridge there is no one to talk to and, as you rightly said, the nights are very empty,” Bradman wrote.

However, Neil Harvey is still alive to this day, at 96 years old, and has spoken about the guilt he felt for costing Bradman the opportunity to finish his career with a batting average above 100.

Harvey had hit a match-winning four in Bradman’s penultimate Test against England. Had Bradman scored those runs, he would have maintained his 100 average.

I’m quite willing to take the blame. But he didn’t know he was going to get a duck in his last Test match… Nobody knew Bradman needed four runs at Leeds; “Nobody knew he needed four runs when he played in his last Test at the Oval,” Harvey said in 2018.

‘Statistics were never mentioned back then; there was no television and no one in the press seemed to know. When they threw the poor guy in, that was it. I wasn’t going to get another chance because we dismissed England for 52 in their first innings.