An explainer video about how life in Australia has become financially impossible has gone viral, with viewers pointing out that the problem is appearing around the world.

Dutch YouTube channel Hindsight’s video posted Nov. 30 said rising housing prices have made home ownership unattainable for younger people and threatens to cement an ongoing generational wealth divide in the nation.

“The Australian dream is to own a home, but that ideal is increasingly out of reach,” the video’s title reads.

The video’s narrator explains that despite Australia’s enormous size, roughly the same as that of the United States minus Alaska, almost the entire population lives in just five capital cities, with approximately 40 percent in Sydney and Melbourne alone.

“The Australian dream is dying,” they said.

According to a 2024 Demographia report, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide are among the top 10 most unaffordable cities in the world, with Hong Kong topping the list.

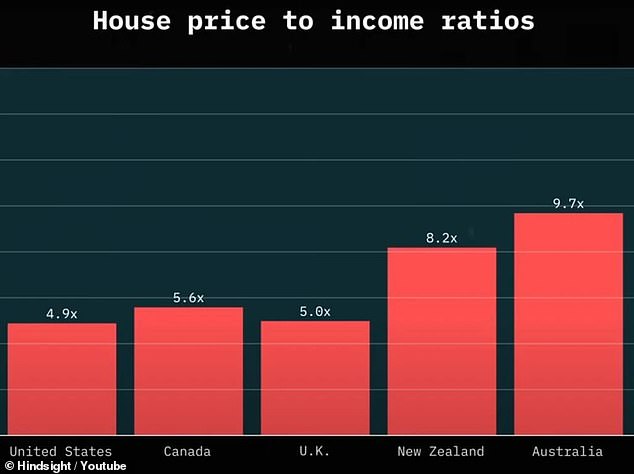

“The average cost of a house doubled (in Australia) from less than $500,000 in 2011 to almost $1 million in 2024. And wages haven’t kept pace,” the narrator explained.

They also referenced figures supported by the latest ANZ Corelogic Housing Affordability Report, which showed Sydney house prices now cost 10 times the median wage.

The average house price in Australia is almost ten times the average salary

“So more and more people are looking to rent and this demand is one of the reasons rents are now out of control, making the Australian dream of buying a home even further out of reach,” said the narrator.

The video explains that a minimum wage worker must spend 68 percent of their income on rent, which “makes it impossible to save” for a deposit.

‘This increases the number of people who will always rent while landlords become incredibly rich. The fear is that this could create a two-class society.”

The video argues that the increasingly competitive rental market has been boosted by more people moving to Australia.

‘In the last two years, Australia has admitted a record number of immigrants. “Critics argue that this was irresponsible because it coincided with extreme difficulties in the construction sector,” the video explains.

Australia is challenged by the rising costs of new construction projects just when they are needed most, with inflation combining with labor and supply chain costs to drive up the price of building a new home by almost a 40 percent.

‘Immigration can help Australia fill gaps in its workforce and, in the form of international students, is generating billions in revenue each year.

‘In fact, education is Australia’s largest non-mineral export. But it also adds to the already growing internal pressures.”

In the video, a woman complained about skyrocketing immigration as Australia battled a housing crisis.

Commenters on the video agreed that it was a big problem not only in Australia but in other countries.

‘When I was growing up in Australia, a person on one salary could afford a house, live comfortably and take the family on holidays. “Now you need at least two salaries and that’s not even enough,” said one commentator.

‘Dear Australia, we have the same problem. “Canada signed,” added a second.

‘Has anyone else noticed that this same story (with slight variations) is happening in seemingly every county in the world right now?’ added a third.

The video notes that in the 1950s, Australia’s economy was growing rapidly and the nation had one of the best standards of living in the world.

«That was when the Great Australian Dream became popular. The ideal became to own a detached house on a quarter-acre block in the suburbs with a garden and a Holden, the real Australian car.

‘This led Australian cities to expand. Today, Melbourne is six times larger than London, but has fewer inhabitants.

‘Sydney is even more extreme. It is 14 times larger than Berlin but only has 2 million more inhabitants.

‘The government stimulated home ownership with policies such as providing grants for first-time homeowners and home ownership jumped from 52 per cent in 1950 to a high of 71 per cent in 1968.

“This happened in other countries too, but Australia was top of the class.”

The Australian dream of a house with a big backyard is already out of reach for many

The filmmakers said Australia’s housing problems began in the 1980s, when there was a shift in priorities and housing went from being seen as a fundamental human right to an asset for investment and profit.

‘The government encouraged people to buy a second home and put it on the market to rent. This increased the number of investors in the market, increased demand and therefore raised prices.’

This change in the perception of housing as a commodity steadily increased prices until it reached a fever pitch when interest rates dropped to almost zero when the Covid pandemic hit in 2020.

‘These extremely low rates made it easier for people to get a home loan, increased demand and drove up prices. In addition to this, the government spent billions of dollars on programs aimed at helping low- and middle-income families buy their first home.’

The filmmakers said it was one of many factors that led to increased demand and that wouldn’t be a problem “if properly balanced with increased supply, but that’s one of the things that went wrong.”

The filmmakers argue that in the 1980s there was a shift in priorities in which housing went from being seen as a fundamental human right to an asset for investment and profit.

They argue that a drop in government-sponsored housing construction for low-income people, along with increased bureaucracy for new housing and a resistance to high-density developments where they are needed, led to supply drying up.

“Most people want more housing, but ‘not in our backyard’ is the resounding chorus.”

The video concludes with a powerful message by pointing out several solutions proposed by economists to solve the real estate crisis.

These include easing planning restrictions, providing more public housing, tightening tax breaks for investors and reforming the way states collect housing taxes.

“It is now up to politicians to convince Australians on how to address this issue… but at least there is some consensus among economists.”